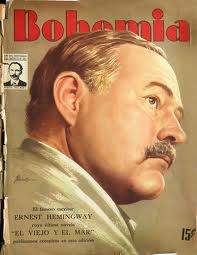

It has been sixty years of the first publication in Spanish of “The Old Man and the Sea”, the famous novel by Ernest Hemingway. The event prompted the magazine Bohemia, of Havana, directed by Miguel Angel Quevedo, who inserted the story in full in the edition corresponding to March 15, 1953. An event that is part of the centennial celebration of Bohemia and in the first visit to Cuba’s of the great American storyteller.

Life magazine had released the novel in English in question before it was published as a book. Paid to the author at the rate of one dollar and ten cents per word, allowing the writer fees for nearly thirty thousand dollars. Bohemia was offered five thousand dollars and Hemingway accepted on condition that the money will buy TVs to the leprosarium patients Corner, south of Havana. Put another condition. The translator should be Lino Novas Calvo.

Today that edition of Bohemia including The Old Man and the Sea is a cult object for collectors and those who are interested in the presence of Hemingway in Cuba. Bohemia was then a circulation that exceeded 259,000 copies and independent pollsters estimated that each copy was read by eight. Circulated not only in Cuba, but throughout the continent, with exceptions like the Dominican Republic, where the satrap Rafael L. Trujillo would not let her go.

The issue in question bears on the cover a magnificent portrait of the writer by Orlando Yanez, regular magazine cover artist. Inside, numerous photographs and drawings fit the novel and the movie seem to anticipate from it was filmed. No credit is given to the photographer or illustrator, but it is stated that the translation is Lino Novas Calvo, which is not true in all Spanish editions of The Old Man and the Sea. In many of them his name is omitted, although they state that it is an authorized translation by the narrator. This is the case in the first edition of the novel Cuban in book form, today another bibliographic rarity that collectors pay top dollar in the markets of old books of Havana.

Recalling that Hemingway called those five thousand pesos Bohemia offered by the publication of his novel was earmarked for the purchase of televisions for the sick of the Corner. In 1953, that amount would be enough to purchase at a retail ten television sets.

Norberto Fuentes, in his book Hemingway in Cuba, says it’s not clear what happened finally with those fees, but later on the same page asserts that “the story ends with televisions installed”. Sources say they have seen in the archives of Finca Vigia, the Cuban writer’s residence, a dozen documents that show irregularities. In some of these letters, magazine management is quick to tell Hemingway that TVs will be purchased in the near future, and in others, that the teams in question are about to be installed. It also retains a letter to Hemingway in Lino it clear that it has nothing to do with the delays, adding that the administration is concerned about the long silence of the writer to him and not respond to their calls. In the end, everything is resolved and the hospital arranged Corner TVs.

Miguel Angel Quevedo

Bohemia became Michelangelo Quevedo, director-owner, a powerful figure, someone with unlimited influence in national life, to the point that came to be said that the direction of Bohemia was the second position of the Republic.

Directed by Miguel Angel Quevedo Bohemia Magazine was one of the most popular news weekly in his days in Cuba and Latin America, known for his political journalism and publishing becoming the leading voice of opposition to the administration of Carlos Prio Socarras and supported the insurrection and revolution against the regime of Fulgencio Batista. On July 26, 1958 the magazine published the Manifesto of the Sierra Maestra, a document whose purpose was the unification of opposites and opposition groups fighting the Batista regime. On January 11, 1959, the roll of the first issue special edition of Bohemia after the revolution was a million copies and was sold within hours.

The relationship with Francisco Saralegui, the Tsar’s role in Cuba and Journal Manager, Quevedo was to invest heavily in the final years of the ’50s. Bohemia opened a new building on the Avenue of Cattle Ranches and acquired Vanities posters and magazines, owned by Alfredo T. Quiles. When the Revolution triumphed had debts exceeding two and a half million pesos. A few months after the revolutionary triumph Miguel A. Quevedo left Cuba dissatisfied with the steps taken by the administration of Fidel Castro who had supported.

Then ensues a period of his life in Cuba is insufficiently known and distorted. Arriving in New York found that the output of Bohemia was secured, and who also had at its disposal a large office and a large apartment. There was Bebo Saralegui, a son of his former partner, and would soon appear Mauricio Carlos Castaneda. The group is completed with the arrival of Lino Novas Calvo and his wife, who had led in the magazine Vanity Cuba.

I guess Quevedo smart enough to realize that this glossy magazine that became Bohemia, that great office, that great apartment, apparatus that allowed anyone to assume the magazine, were funded by the CIA. But did not realize that Saralegui, and Herminia Portal Castañeda and do not know how Lino Novas Calvo conspired against him engaged, as they were in Bohemia leaving the hand, each time with a smaller print run, and throw walking and strengthen another magazine, Vanity Continental, what they got.

When Quevedo realized of the betrayal realized nothing could be done. He then asked to leave the U.S. Was set to end in Caracas.

He thought that society with Capriles and De Armas, major distributors of magazines, would ensure the triumph of Bohemia. New failure. Bohemia was no longer even a shadow of its former self and make it more bitter drink was made clerk who believed their partners. He was the nominal chief of the magazine. But he was not allowed and reached a decision prevented from entry to his own office.

In August 1969, Quevedo ended up committing suicide. It was a bad hereditary. His father was also deprived of his life.

Sources: Wiki/CiroBianchi/various/InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

Ernest Hemingway, Bohemia and Miguel A. Quevedo

Ernest Hemingway, Bohemia y Miguel A. Quevedo.

Se cumplieron sesenta años de la primera publicación en español de “El viejo y el mar”, la célebre novela de Ernest Hemingway. El acontecimiento lo propició la revista Bohemia, de La Habana, dirigida por Miguel Angel Quevedo, que insertó de manera íntegra el relato en su edición correspondiente a 15 de marzo de 1953. Suceso que se inscribe en la celebración del centenario de Bohemia y la primera visita a Cuba del gran narrador norteamericano.

La revista Life había dado a conocer en inglés la novela en cuestión antes de que se publicara como libro. Pagó a su autor a razón de un dólar con diez centavos por palabra, lo que permitió al escritor honorarios por casi treinta mil dólares. Bohemia le ofreció cinco mil pesos y Hemingway aceptó a condición de que con ese dinero se compraran televisores para los enfermos del leprosorio de El Rincón, al sur de la capital cubana. Puso otra condición más. El traductor debía ser Lino Novás Calvo.

Hoy aquella edición de Bohemia que incluyó El viejo y el mar es un objeto de culto para coleccionistas y los que se interesan por la presencia de Hemingway en Cuba. Bohemia tenía entonces una tirada que superaba los 259 000 ejemplares y encuestadores independientes estimaban que cada ejemplar era leído por ocho personas. Circulaba no solo en Cuba, sino en todo el continente, con excepciones como República Dominicana, donde el sátrapa Rafael L. Trujillo no la dejaba entrar.

La edición en cuestión lleva en la portada un magnífico retrato del escritor realizado por Orlando Yánez, portadista habitual de la revista. En su interior, numerosas fotografías y dibujos calzan la novela y parecen anticipar la película que a partir de ella se filmara. No se da crédito al fotógrafo ni al ilustrador, pero sí se consigna que la traducción es de Lino Novás Calvo, lo que no sucede en todas las ediciones en español de El viejo y el mar. En muchas de ellas se omite su nombre, aunque hacen constar que se trata de una traducción autorizada por el narrador. Así sucede en la primera edición cubana de la novela en forma de libro, hoy otra rareza bibliográfica que los coleccionistas pagan a precio de oro en los mercados de libros viejos de La Habana.

Recordando que Hemingway pidió que aquellos cinco mil pesos que le ofreció Bohemia por la publicación de su novela se destinaran a la compra de televisores para los enfermos de El Rincón. En 1953, esa suma alcanzaría para adquirir en un comercio minorista unos diez aparatos de televisión.

Norberto Fuentes, en su libro Hemingway en Cuba, afirma que no está claro que pasó finalmente con esos honorarios, pero más adelante asevera en la misma página que “la historia termina con los televisores instalados”. Fuentes asegura haber visto en los archivos de Finca Vigía, la residencia cubana del escritor, una docena de documentos que evidencian irregularidades. En algunas de esas cartas, la administración de la revista se apresura a informar a Hemingway que los televisores serán adquiridos en fecha próxima, y en otras, que los equipos en cuestión están a punto de ser instalados. Se conserva asimismo una carta de Lino a Hemingway en la que le aclara que no tiene nada que ver con las demoras de la administración y añade que le preocupa el largo silencio del escritor para con él y que no responda a sus llamadas. Al final, todo se resolvió y el hospital de El Rincón dispuso de los televisores.

Miguel Angel Quevedo

Bohemia convirtió a Miguel Ángel Quevedo, su director-propietario, en una figura poderosísima, alguien con influencia ilimitada en la vida nacional, al punto de que llegó a decirse que la dirección de Bohemia era la segunda posición de la República.

Dirigido por Miguel Ángel Quevedo la Revista Bohemia fue uno de los semanarios de noticias más populares en sus días en Cuba y América Latina, conocida por su periodismo político y sus editoriales convirtiendose en la principal voz de la oposición de la administración de Carlos Prio Socarras y apoyó la insurrección y la revolución en contra del régimen de Fulgencio Batista. El 26 de julio de 1958 la revista publicó el manifiesto de Sierra Maestra, un documento cuyo propósito fue la unificación de los grupos contrarios y opositores que combatían el régimen de Batista. El 11 de enero de 1959, la tirada del primer número edición especial de Bohemia después de la revolución fue de un millón de copias y fue vendidas en pocas horas.

La relación con Francisco Saralegui, el zar del papel en Cuba y administrador de la revista, llevó a Quevedo a hacer grandes inversiones en los años finales de la década de los 50. Bohemia estrenó un nuevo edificio en la Avenida de Ranchos Boyeros y adquirió las revistas Carteles y Vanidades, propiedad de Alfredo T. Quilés. Al triunfar la Revolución tenía deudas que superaban los dos millones y medio de pesos. A los pocos meses del triunfo revolucionario Miguel A. Quevedo abandonó Cuba descontento con los pasos seguidos por la administración de Fidel Castro a quien habia apoyado.

Sobreviene entonces un periodo de su vida que en Cuba se ha conocido de manera insuficiente y tergiversada. Al llegar a Nueva York encontró que la salida de Bohemia estaba asegurada, y que tenía además a su disposición una gran oficina y un gran apartamento. Allí estaba Bebo Saralegui, uno de los hijos de su antiguo socio, y no tardaría en aparecer Carlos Mauricio Castañeda. El grupo se completaría con la llegada de Lino Novás Calvo y su esposa, que había dirigido en Cuba la revista Vanidades.

Le supongo a Quevedo la inteligencia suficiente para percatarse que aquella revista de lujo en que se convirtió Bohemia, aquella gran oficina, aquel gran apartamento, todo aquel aparataje que permitía asumir la revista, estaban financiados por la CIA. Pero no se percató que Saralegui, Castañeda y Herminia del Portal y no sé hasta qué punto Lino Novás Calvo se confabularon en su contra empeñados, como estaban, en dejar a Bohemia de la mano, cada vez con una tirada más reducida, y echar a andar y fortalecer otra revista, Vanidades Continental, lo que consiguieron.

Cuando Quevedo se percató de la traición nada podía hacer. Quiso entonces salir de EE UU y para hacerlo debió reconocer a la CIA una deuda de casi cinco millones de dólares. Se estableció al fin en Caracas. Pensó que la sociedad con los Capriles y los De Armas, grandes distribuidores de revistas, le asegurarían la salida de Bohemia. Nuevo fracaso. Bohemia no era ya ni la sombra de lo que fue y para hacerle el trago más amargo se vio convertido en empleado de los que creyó sus socios. Era el director nominal de la revista. Pero no se le permitía decisión alguna y llegó a impedírsele la entrada a su propia oficina.

En agosto de 1969, Quevedo terminó suicidándose. Era un mal hereditario. También su padre se había privado de la vida.

Sources: Wiki/CiroBianchi/various/InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

Ernest Hemingway, Bohemia and Miguel A. Quevedo