Until the last decades of the 18th Century, Cuba was a relatively underdeveloped island with an economy based mainly on cattle raising and tobacco farms. The intensive cultivation of sugar that began at the turn of the nineteenth century transformed Cuba into a plantation society, and the demand for African “slaves”, who had been introduced into Cuba from Spain at the beginning of the 16th century, increased dramatically. The slave trade with the West African coast exploded, and it is estimated that almost 400,000 Africans were brought to Cuba during the years 1835-1864. [That’s roughly 1150 per month for 29 years!] In 1841, African slaves made up over 40% of the total population.

The late flourishing of the Cuban sugar industry and the persistence of the slave trade into the 1860s are two important reasons for the remarkable density and variety of African cultural elements in Cuba. Fernando Ortiz Counted the presence of over one hundred different African ethnic groups in 19th century Cuba, and estimated that by the end of that century fourteen distinct “nations” had preserved their identity in the mutual aid associations and social clubs known as cabildos, societies of free and enslaved blacks from the same African “nation,” which later included their Cuban-born descendants. Soon after Emancipation in 1886, cabildos were required to adopt the name of a Catholic patron saint, to register with local church authorities and when dissolved, to transfer their property to the Catholic Church.

Paradoxically, it was within the church sponsored cabildos that Afro-Cuban religions and identities coalesced. Even after they were officially disbanded at the end of the 19th century, many were kept up on an informal basis, and were known popularly by their old African names. Some survive to this day. The cabildos not only preserved specific African practices, their members also creatively reunited and resynthesized many regional African traditions, some, as in the case of the Yoruba, long separated by migration and war.

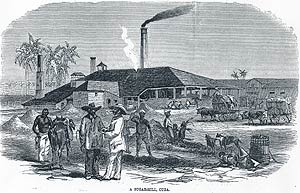

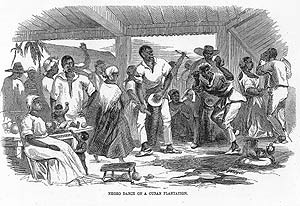

While the formally organized cabildos were a primarily urban phenomenon, individual and collective African practices also continued to flourish at the sugar estates, known as ingenios or centrales. These were more like small, self-contained industrial townships than “plantations.” About 80% of the newly-arrived [Africans] known as bozales, were sent to them, and many centrales became centers of specific African “nations.”

Forged in the cabildos and amidst the grueling labor at the sugar mills, four major Afro-Cuban divisions (Lucumí, Arará, Abakuá, Kongo) are represented in Cuba.

We’ll start with:

Yoruba (Oloku mi)

Cuba’s transformation into a sugar-growing island is intimately linked via the slave trade to African history. It coincided with the collapse of the Oyo empire of Nigeria after decades of internal strife among the Yoruba and warfare with their Fulani neighbors to the north and Dahomeans to the west. Many Yoruba were taken to Cuba very late in the slave trade, especially during the years 1820-1840, when they formed a majority of [Africans] sent across the Atlantic from the ports of the Bight of Benin. The included several Yoruba-speaking subgroups, including the Ketu, Ijesha, Egbado, Oyo, Nago and others.

In Cuba, Yoruba speakers became known by the collective term Lucumí, after a Yoruba phrase, oloku mi, meaning my friend. As a result of slavery, the lineages and kin groups that had supported worship of the various orisha were disrupted. A new religion called santería arose, which grouped together many orisha, each of which became identified with a Catholic saint on whose day festivals would be held. From the ethnically-based cabildos of colonial Cuba, santería became organized into individual “houses,” known as casas de ocha. It has since spread far beyond its original ethnic base, both within and outside of Cuba.

Entry into santiería is through a long process of initiation, during which an orisha is seated in the head of an iyawó, or initiate. As in other African-based religions in the Americas, music plays a critical role in bringing the orisha to dance in the heads of the initiates, and in creating and sustaining the ritual setting. The most sacred instruments among the Lucumí are the trio of batá drums, which when consecrated are called fundamento and are said to hold an indwelling deity called Añá. Batá are played at initiation ceremonies, in the presentations of initiates to the drums, at funerals, in ceremonies honoring the ancestors and in others that call for sacralized drums. Other Lucumí styles include ensembles of beaded gourds, known as abwe or chekeré, which are played, for example, in ceremonies celebrating ritual “birthdays;” and sets of bembé drums, usually cylindrical in shape, which may show non-Yoruba influences and are usually found in rural areas.

In the 1950s there was an increased infusion of Lucumí ritual styles and subject matter into the Cuban popular music mainstream. One important event was the release of an LP called Santero, which featured batá drummers from the Havana area and such popular singers as Mercedes Valdes, Celia Cruz and others, all singing in Lucumí. Celia Cruz and Gina Martin also recorded songs in conjunto format that were homages to different orisha. More recently, the Cuban group Mezcla, featuring the great akpon (Lucumí song leader) Lázaro Ros, has been recording a new ritual-popular music, some in the style of French Caribbean zouk, some influenced by jazz and rock.

Batá are a set of three double-headed, hourglass-shaped drums. The largest iyá (mother), [E-Yah], is the master drum. The iyá calls the rhythms in, calls changes and conversations. Next in size, the itótele (means: follows completely), [E-Toe-Teh-Lay], follows the direction of the iyá answering the conversation calls and rhythm changes. The smallest drum okónkolo [O-Kon-Ko-Lo], sometimes referred to as Omele [O-May-Lay (strong child)], , for the most part plays ostinato patterns, also changing rhythms from the calls of the iyá.

Iyesá

The Iyesá are a Lucumí “nation” still recognized as having a distinct musical style. Iyesá drums are played with sticks, usually in groups of three, with a fourth drum added for certain toques. Their combined rhythmic patterns are more unified than the three-way conversation among the batá drums. Agogó, or dance gongs, of different pitches that play interlocking patterns accompany these drums.

The last surviving Iyesá cabildo in Cuba is San Juan Batista, which was founded in 1854 in the City of Matanzas.

Sources: AfricanLinks/ InternetPhotos/ TheCubanHistory.com

Afro-Cuban Identities (I)/ The Cuban History/ Arnoldo Varona,Editor

Identidades Afro-Cubanas (I)

Hasta las últimas décadas del siglo 18, Cuba era una isla relativamente subdesarrollada con una economía basada principalmente en la cría de ganado y plantaciones de tabaco. El cultivo intensivo de azúcar que comenzó a finales del siglo XIX, transformó a Cuba en una sociedad de plantación, y la demanda de africanos “esclavos”, que habían sido introducidos en Cuba desde España a principios del siglo 16, aumentó dramáticamente. El comercio de esclavos con la costa occidental de África explotó, y se estima que casi 400.000 africanos fueron traídos a Cuba durante los años 1835-1864. [Eso es más o menos 1.150 al mes durante 29 años!] En 1841, los esclavos africanos representaban más del 40% de la población total.

El florecimiento tardío de la industria azucarera cubana y la persistencia de la trata de esclavos en la década de 1860 son dos razones importantes para la notable densidad y la variedad de elementos culturales africanos en Cuba. Fernando Ortiz contó con la presencia de más de cien diferentes grupos étnicos africanos en el siglo 19 Cuba, y se estima que para finales de ese siglo catorce distintas “naciones” han conservado su identidad en las asociaciones de ayuda mutua y clubes sociales conocidos como los cabildos, las sociedades de libres y esclavos negros africanos de la misma “nación”, que más tarde incluyó a sus descendientes nacidos en Cuba. Poco después de la emancipación en 1886, los cabildos están obligados a adoptar el nombre de un santo patrono católico, para registrarse ante las autoridades locales de la iglesia y cuando se disuelve, para transferir su propiedad a la Iglesia Católica.

Paradójicamente, fue en los cabildos auspiciados por la iglesia de que las religiones afrocubanas y las identidades se unieron. Incluso después de que se disolvió oficialmente a finales del siglo 19, muchos se mantienen de manera informal, y eran conocidos popularmente por sus nombres africanos de edad. Algunos sobreviven hasta nuestros días. Los cabildos no sólo conservan las prácticas específicas de África, sus miembros también se reunió de manera creativa y sintetizar muchas de las tradiciones regionales de África, algunos, como en el caso de los yoruba, siempre separadas por la migración y la guerra.

Mientras que los cabildos organizados formalmente eran un fenómeno principalmente urbano, prácticas africanas individuales y colectivas también continuó floreciendo en las plantaciones de azúcar, conocidas como ingenios o centrales. Estos eran más bien pequeños, autónomos municipios industriales que “las plantaciones.” Alrededor del 80% de los recién llegados [los africanos] conocido como bozales, fueron enviados a ellos, y muchas centrales se convirtieron en centros específicos de África “naciones”.

Forjado en los cabildos y en medio de la mano de obra agotadora en los centrales azucareros, las cuatro principales divisiones afrocubanos (Lucumí, Arará, Abakuá, Congo) están representados en Cuba.

Vamos a empezar con:

Yoruba (Oloku millas)

La transformación de Cuba en una isla azucarera está íntimamente ligado a través de la trata de esclavos en la historia de África. Coincidió con el colapso del imperio de Oyo de Nigeria después de décadas de luchas internas entre los Yoruba y la guerra con sus vecinos Fulani en el norte y Dahomeans hacia el oeste. Muchos Yoruba fueron llevados a Cuba muy tarde en el comercio de esclavos, especialmente durante los años 1820-1840, cuando se formaron la mayoría de [los africanos] envió a través del Atlántico desde los puertos de la bahía de Benín. El precio incluye varios subgrupos de habla yoruba, entre ellos el Ketu, Ijesha, Egbado, Oyo, Nago y otros.

En Cuba, los oradores se convirtió en yoruba lucumí se conoce por el término colectivo, después de una frase yoruba, oloku millas, es decir, mi amigo. Como resultado de la esclavitud, los linajes y grupos familiares que habían apoyado a la adoración del orisha diferentes se vieron afectadas. Una nueva religión llamada santería surgió, que agrupa a orisha muchos, cada uno de ellos se identificó con un santo católico en cuyo día se celebrará los festivales. A partir de los cabildos de base étnica de la Cuba colonial, la santería se organizaron en “casas particulares”, conocido como casas de Ocha. Desde entonces se ha extendido mucho más allá de su base original, étnico, tanto dentro como fuera de Cuba.

Entrada en santiería es a través de un largo proceso de iniciación, durante el cual un orisha se asienta en la cabeza de un Iyawó, o iniciar. Al igual que en otras religiones de origen africano en las Américas, la música juega un papel esencial para lograr que el orisha a bailar en la cabeza de los iniciados, y en la creación y el mantenimiento de la configuración de ritual. Los instrumentos más sagrado entre los Lucumí son el trío de tambores batá, que cuando consagrada están llamados Fundamento y se dice que tienen una deidad que mora en nosotros llamada Ana. Batá se juegan en las ceremonias de iniciación, en las presentaciones de los iniciados a los tambores, en los funerales, en las ceremonias en honor de los antepasados y en otros que requieren tambores sacralizadas. Otros estilos incluyen Lucumí conjuntos de las calabazas de cuentas, conocidos como abwe o chekeré, que se juegan, por ejemplo, en las ceremonias rituales que celebran “cumpleaños”, y conjuntos de tambores de Bembe, generalmente de forma cilíndrica, que pueden mostrar no Yoruba influencias y son generalmente se encuentran en las zonas rurales.

En la década de 1950 hubo un aumento de la infusión de estilos rituales Lucumí y el tema en la corriente de música popular cubana. Un hecho importante fue el lanzamiento de un LP llamado Santero, que contó con tambores batá de la zona de La Habana y cantantes tan populares como Mercedes Valdés, Celia Cruz y otros, todos cantando en Lucumí. Celia Cruz y Gina Martin también grabó canciones en formato de conjunto que son homenajes a orisha diferente. Más recientemente, el grupo cubano Mezcla, con la gran akpon (líder de canto Lucumí) Lázaro Ros, ha estado grabando un nuevo ritual de la música popular, algunas en el estilo de zouk del Caribe francés, algunos influenciados por el jazz y el rock.

Batá son un conjunto de tres con dos puntas, con forma de reloj de arena tambores. El más grande Iya (madre), [E-Yah], es el tambor principal. El iyá llama a los ritmos, las llamadas y conversaciones cambios. A continuación, en tamaño, el itótele (significa: sigue por completo), [E-Toe-Teh-Lay], sigue la dirección de la iyá responder a las llamadas de conversación y cambios de ritmo. El tambor más pequeño okónkolo [O-Kon-Ko-Lo], a veces se denomina Omele [O-mayo-Lay (hijo fuerte)], en su mayor parte reproduce los patrones de ostinato, también está cambiando los ritmos de las llamadas del AIA.

Iyesá

El Iyesá son lucumí “nación” sigue siendo reconocida por tener un estilo musical distinto. Iyesá tambores se tocan con palos, por lo general en grupos de tres, con un tambor cuarto adicional para ciertos toques. Sus patrones rítmicos combinados son más unificada que la conversación a tres bandas entre los tambores batá. Agogo, o la danza, los gongs de diferentes tonos que se reproducen los patrones entrelazados acompañar a estos tambores.

El último superviviente Iyesá cabildo en Cuba es la de San Juan Bautista, que fue fundada en 1854 en la ciudad de Matanzas.

Fuentes: AfricanLinks/InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

Identidades AfroCubanas/ The Cuban History/ Arnoldo Varona, Editor

Afro-Cuban Identities (I)

Afro-Cuban Identities (I)