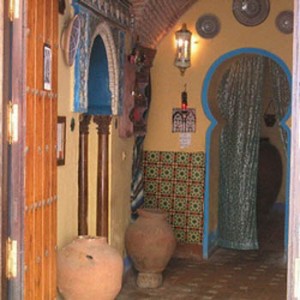

The Arab presence in Cuba dates from the early years of the colony and can be described as a Hispanic-Moorish and North African Moorish-composed of slaves and free people converted to Catholicism. This presence left his greatest mark on the architecture, because during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries prevailed in Havana, Remedios, Santiago de Cuba and other cities in the Moorish style, combining Western and Arab elements, important heritage school building Moorish Seville. If they left a singular mark Cuban colonial architecture, courtyard, arches, ceilings paneled ceiling, lucetas, tiles and mosaics, Arab culture is assimilated during the Republic of Cuba and leaves no visible trace. It is estimated that today in the Arabic Island colony form, between natives and descendants, some 50 thousand people. There is a house in Havana of the Arabs, which traps the stroke of that culture and some restaurants who strive to recreate the atmosphere of the Arabian Nights.

Farah Anton was the first Arab who came to Cuba in order to settle in these lands. He did it in 1879 and opened a path that followed until 1936 about 40 thousand people, mainly men, in essence, devoted to trade, in preference to the tissues and silks imported from their home regions. Some, very few, managed to establish warehouses and import houses, the most, they went from street vendors and put a note in the principal picturesque Cuban cities. Others are devoted to jewelry. The Lebanese Isaac Stefano, sold to the Cuban state, in the 20, the gem than at the Capitol in Havana marked the kilometer zero of all distances in the country. The gem in question had been part of one of the crowns of Nicholas II, last Tsar of Russia. A notable late Cuban poet, Fayad Jamis, was of Arab descent, his friends called him El Moro, which is familiarly known here as Arabs and descendants. Pedro Kouri is one of the glories of Cuban medicine. His son Gustavo heads the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Havana, which bears his name and whose work is recognized internationally. This is a family that, over time, gives the Cuban health very illustrious names. A family of Arab descent is ascribed the authorship of the guayabera, Cuba’s national garment, and although there seems to be true, must certainly have helped to shape that shirt is synonymous with elegance and comfort. Also from that source was George Nayor, thinking head and star of the notorious assault on the Royal Bank of Canada in Havana in 1947, the largest cash robbery in the history of Cuba.

Unlike the Chinese, who had and have your neighborhood in Havana, there was never an Arab neighborhood here. For the Arabic-speaking resident sought places that reminded them of something those sites from which they came. The causeway populous Monte, one of the most lively shopping streets of Havana and its vicinity were the focus of your preferences.

Lonely men married Cuban and very few kept their faith. Catholics were married and baptized their children according to the ritual of that church. Many of the Lebanese who settled in Cuba were Maronite Christians of the slope, and that led to that in the decade of 40 of the last century image of Saint Maron will be located in a Catholic parish in Havana, on the other hand, officiated Lebanese priests.

Many of those emigrants castellanizaron their names upon arrival in Cuba, and usually not taught their tongue to Cuban children. They created their societies and their papers were in Arabic or Spanish and Arabic. And they insisted, they and their descendants, to maintain their culinary traditions, without mystification.

Because if you cook like the Spanish and Italian palate adapted to Cuban, Arab cuisine keeps, or tries to maintain its purity. When it comes to Arab cuisine in Cuba is meant, in essence, to the kitchens Lebanese, Syrian and Palestinian, because these nationalities the most widely represented, although known and elaborate dishes Egyptians, Libyans and Iraqis, among others.

It is a cuisine that has not been popularized. Survives in the homes of the Arabs and their descendants who are preparing their dishes according to recipes handed down from mother to daughter and with the use of so-called Arab spice mixture of cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice and cloves, and not with spices that cubanizan the kitchen.

There just are admittedly a real effort because the kitchen did not die in Cuba, which could happen, without remedy, if one considers that the colony has received in recent years substantial impact that immigrants strengthen, rather has been depopulated. Hence resulting commendable efforts of the Arab Union for preservation.

Since there is no rule without exception, circumstances force some adaptations, sometimes minimal, but adaptations to the end. Such is the case of the use of peanuts in place of the almond and pistachio, not always easy to get now, the lack of some seeds, which seeks to remedy as possible, and impersonation of the beans for the peas in hummus , which is made here, and that is another adaptation, with mayonnaise.

Sources:CiroBianchiRoss/UvaC./InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

Los Arabes en Cuba

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

HISTORIA DE LOS ARABES CUBANOS.

La presencia árabe en Cuba data de los primeros años de la colonia y puede describirse como hispano-morisca y morisco-norafricana, compuesta por esclavos y personas libres convertidas al catolicismo. Esta presencia dejó su mayor huella en la arquitectura, pues durante el siglo XVII y principios del XVIII predominó en La Habana, Remedios, Santiago de Cuba y otras ciudades el estilo mudéjar, que combinaba elementos occidentales y árabes, herencia importante de la escuela de construcción morisca de Sevilla. Si ellos dejaron una huella singular en la arquitectura colonial cubana -patio central, arcadas, techos de alfarje, lucetas, mosaicos y azulejos- la cultura árabe durante la República se asimila a la cubana y no deja una huella visible. Se calcula que hoy en la Isla la colonia árabe la conforman, entre originarios y descendientes, unas 50 mil personas. Hay en La Habana una Casa de los Árabes, que atrapa el trazo de esa cultura y algunos restaurantes que se afanan por recrear la atmósfera de Las mil y una noches.

Fue Antón Farah el primer árabe que llegó a Cuba con el propósito de asentarse en estas tierras. Lo hizo en 1879 y abrió un camino que hasta 1936 siguieron unas 40 mil personas, hombres fundamentalmente que, en lo esencial, se dedicarían al comercio, con preferencia al de los tejidos y las sedas que importaban de sus regiones de origen. Algunos, muy pocos, consiguieron establecer almacenes y casas importadoras; los más, se las pasaron de vendedores ambulantes y ponían una nota pintoresca en las principales ciudades cubanas. Otros se dedicaron a la joyería. El libanés Isaac Estéfano, vendió al Estado cubano, en los años 20, el brillante que en el Capitolio de La Habana marcaba el kilómetro cero de todas las distancias del país. La gema en cuestión había sido parte de una de las coronas de Nicolás II, último zar de Rusia. Un notable poeta cubano ya fallecido, Fayad Jamís, tenía ascendencia árabe; sus amigos le llamaban El Moro, que es como se llama aquí familiarmente a árabes y descendientes. Pedro Kourí es una de las glorias de la medicina cubana. Su hijo Gustavo dirige el Instituto de Medicina Tropical, de La Habana, que lleva su nombre y cuyo quehacer se reconoce internacionalmente. Se trata de una familia que, a través del tiempo, dota a la salud cubana de nombres muy ilustres. Una familia descendiente de árabes se atribuye la paternidad de la guayabera, prenda nacional de Cuba, y aunque no parece que sea cierto, sin duda debe haber contribuido a conformar esa camisa que es sinónimo de elegancia y comodidad. También de ese origen era Jorge Nayor, cabeza pensante y protagonista del sonado asalto al Royal Bank de Canadá en La Habana de 1947; el mayor robo de dinero en efectivo que registra la historia de Cuba.

A diferencia de los chinos, que tuvieron y tienen su barrio en la capital cubana, no existió nunca aquí un barrio árabe. Para residir los arabófonos buscaron lugares que les recordaran en algo aquellos sitios de donde provenían. La populosa calzada de Monte, una de las arterias comerciales habaneras más movidas, y sus inmediaciones fueron el centro de sus preferencias.

Los hombres solos casaron con cubanas y muy pocos mantuvieron su fe. Se hicieron católicos y contrajeron matrimonio y bautizaron a sus hijos según el ritual de esa iglesia. Muchos de los libaneses que se radicaron en Cuba eran cristianos de la vertiente maronita, y eso motivó que en la década de los 40 del siglo pasado la imagen de San Marón se emplazara en una parroquia católica habanera en la que, por otra parte, oficiaban sacerdotes libaneses.

Muchos de aquellos emigrantes castellanizaron sus nombres tras la llegada a Cuba, y, por lo general, no enseñaron su lengua a los hijos cubanos. Crearon sus sociedades y tuvieron sus periódicos en árabe o en español y árabe. Y se empeñaron, ellos y sus descendientes, en mantener sus tradiciones culinarias, sin mistificaciones.

Porque si cocinas como la española y la italiana se adaptaron al paladar cubano, la cocina árabe mantiene, o intenta mantener, su pureza. Cuando se habla de cocina árabe en Cuba se alude, en lo esencial, a las cocinas libanesa, siria y palestina, por ser esas nacionalidades las más ampliamente representadas, aunque se conocen y elaboran platos egipcios, libios e iraquíes, entre otros.

Es una cocina que no se ha popularizado. Pervive en los hogares de los árabes y sus descendientes que siguen elaborando sus platos según recetas trasmitidas de madres a hijas y con el empleo del llamado condimento árabe –mezcla de canela, nuez moscada, pimienta dulce y clavo de olor- y no con las especias que cubanizan la cocina.

Hay, justo es reconocerlo, un verdadero empeño porque esa cocina no muera en Cuba, lo que podría suceder, sin remedio, si se tiene en cuenta que la colonia no ha recibido en los últimos años golpes sustanciales de emigrados que la fortalezcan; más bien se ha despoblado. De ahí que resulten encomiables los esfuerzos de la Unión Árabe por preservarla.

Como no hay regla sin excepción, las circunstancias obligan a algunas adaptaciones, mínima a veces, pero adaptaciones al fin. Tal es el caso del empleo del maní en sustitución de la almendra y el pistacho, no siempre fáciles de conseguir ahora; la falta de algunas semillas, que se intenta remediar como se pueda, y la suplantación de los garbanzos por los chícharos en el hummus, que se elabora aquí, y esa es otra adaptación, con salsa mayonesa.

Sources:CiroBianchiRoss/UvaC./InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

Los Arabes en Cuba

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

THE CUBAN-ARABS. HISTORY * HISTORIA DE LOS ARABES-CUBANOS.

THE CUBAN-ARABS. HISTORY * HISTORIA DE LOS ARABES-CUBANOS.