The music of the aborigines that the Spaniards found in Cuba and other Caribbean islands did not interest the settlers. They were looking for gold and silver and they did not find them, at least in the quantities they sought. Havana, once settled on the north coast, becomes the port of forced entry of ships that come and go between Spain and America.

Every year two fleets left from Seville. One was going to Mexico and to ports of Central America. Another went to Cartagena and eventually to Argentina. During the winter both fleets met in Havana and from here, together, made the return to Spain, in March.

Thus, the crews of the ships spent long time in Havana between parties and leisures and that became a true laboratory of musical experimentation. The music brought by Spanish sailors and soldiers was intermingled with African music collected in Havana and other ports, and also with indigenous music of advanced cultures such as the Inca and the Aztec. On their return to Seville these men carried the new creations that soon became popular. To these cantes or songs that came and went, they were called cantes back and forth and could not always determine their origin.

In this way the creation of new musical forms or tendencies begins: the gayumba, the chacona, the zarambeque, the zarabanda, the zambapalo, the fandango … It is possible that these forms were developed or perfected and spread in the immense redoma that was La Havana then, cosmopolitan port of forced stay for long weeks for travelers, sailors and soldiers. It is possible, I repeat, but we can not prove it. Yes there is a form that has a proven Cuban origin or, habanero. It is the chuchumbé. They are taken to Veracruz, in 1776, a group of mestizos from Havana. It is a dance that enters Mexico with bad luck. By its picaresque stanzas, by its provocative movements, raised of tone, it condemns the Holy Inquisition.

Music in Cuba from the Haitian Revolution.

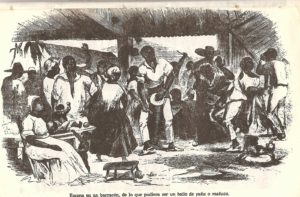

French settlers who, together with their slaves, fled Haiti in 1791 and settled in the eastern portion of the island, bring or revive rhythmic elements from Africa that reach extraordinary development and repercussion in Cuba. They are the cinquillo and the tango congo or habanera, that will appear in the first contradictions published in Havana, in 1803 and in previous guarachas. It is possible that it existed and will be used more narrowly among Afro-Cubans, but the fact is that the French presence acted at least as a catalyst in the dissemination of this rhythm, which quickly became popular inside and outside Cuba.

It adds that in 1836, it appears published in the News of Both Worlds, of Mexico, a habanera titled The pepper. He says: “We already had an export musical item.” It was classified as a Havana counterpart. There was a Spanish dance, an English dance … It is logical to add the gentilicio to identify it: Habanera contradanza. But such was the magic force, the attraction of Havana that was enough to say habanera. Unintentionally, he warns, “Cuba had created what we now call a trademark. Unlike other commercial products that need the gentilicio, the new musical product was enough with that, to be habanero ».

It began to circulate outside of Cuba. From 1840 onwards, Habaneras were written, sung and danced in Mexico, in Venezuela, in Puerto Rico, in many other places in the Americas, and especially in Spain, even if not by a Cuban, but by a Basque, Sebastian Yradier. He writes The Dove in 1860 … “When I left Havana, God is my strength.” And Yradier affirms in the following verse: “No one has seen me leave, if it was not me” It was not necessary to be in Cuba to write a habanera. Many of them were written without their authors ever standing on the Island. But whether Yradier was or was not secondary, merely anecdotal. It does not detract from the popularity of his Paloma, which continues to sing as a standard of Cuban music.

..Two other habaneras were as famous as La Paloma. I am referring to El arreglito, by Yradier himself, and O sole mio by Maestro Di Capua; Another standard of international popular music. Bizet used El arreglito for the famous habanera of his opera Carmen. The sarabande and the chacona were also related. Chabrier, Debussy, Ravel, Fauré and Saint Saens used the habanera. Laparra composed an opera with that name, La habanera. Albéniz and Falla grow it in Spain. Appears in zarzuelas. It is obliged here to mention the name of the Matancero José White. After a ritual stage in Paris, he triumphs in Europe in a roundabout way. Write The beautiful Cuban, the most beautiful of the habaneras.

Breves notas sobre los orígenes de la música cubana y su repercusión internacional.

..La música de los aborígenes que los españoles encontraron en Cuba y otras islas del Caribe no interesó a los colonizadores. Buscaban oro y plata y no los encontraron, al menos en las cantidades que ambicionaban. La Habana, una vez asentada en la costa norte, se convierte en el puerto de recala forzosa de los buques que vienen y van entre España y América.

Cada año partían dos flotas desde Sevilla. Una se dirigía a México y a puertos de América Central. Otra iba a Cartagena y eventualmente a la Argentina. Durante el invierno ambas flotas se reunían en La Habana y desde aquí, juntas, hacían el regreso a España, en marzo.

Así, las tripulaciones de los buques pasaban largo tiempo en La Habana entre fiestas y ocios y eso se convertía en un verdadero laboratorio de experimentación musical. La música que traían marineros y soldados españoles se entremezclaba con la música africana recogida en La Habana y en otros puertos, y también con música indígena de culturas avanzadas como la inca y la azteca. A su regreso a Sevilla esos hombres llevaban las nuevas creaciones que no tardaban en popularizarse. A esos cantes o cantos que iban y venían, se les denominó cantes de ida y vuelta y no siempre podía determinarse su origen.

De esa manera empieza la creación de nuevas formas o tendencias musicales: la gayumba, la chacona, el zarambeque, la zarabanda, el zambapalo, el fandango… Es posible que esas formas se gestaran o perfeccionaran y se divulgaran en la inmensa redoma que era La Habana de entonces, puerto cosmopolita de estadía forzosa durante largas semanas para viajeros, marineros y soldados. Es posible, repito, pero no podemos probarlo. Sí hay una forma que tiene un comprobado origen cubano o, habanero. Es el chuchumbé. Lo llevan a Veracruz, en 1776, un grupo de mestizos salidos de La Habana. Es un baile que entra en México con mala suerte. Por sus estrofas picarescas, por sus movimientos provocativos, subidos de tono, lo condena la Santa Inquisición.

La Música en Cuba a partir de la Revolución Haitiana.

Los colonos franceses que, junto con sus esclavos, pudieron huir de Haití en 1791 y se asentaron en la porción oriental de la Isla traen o reavivan elementos ritmáticos procedentes de África que alcanzan en Cuba desarrollo y repercusión extraordinarios. Son el cinquillo y el tango congo o habanera, que aparecerá en las primeras contradanzas publicadas en La Habana, en 1803 y en guarachas anteriores. Es posible que existiera y se usará más limitadamente entre los afrocubanos, pero lo cierto es que la presencia francesa actuó por lo menos como catalizador en la diseminación de este ritmo, que con rapidez se hizo popular dentro y fuera de Cuba.

Añade que en 1836, aparece publicada en el Noticioso de Ambos Mundos, de México, una habanera titulada La pimienta. Precisa: «Ya teníamos un artículo musical de exportación». Se le catalogó como contradanza habanera. Había una danza española, una danza inglesa… Es lógico que se le agregara el gentilicio para identificarla: contradanza habanera. Pero tal era la fuerza mágica, la atracción que ejercía La Habana que bastaba con decir habanera. Sin proponérselo, advierte, «Cuba había creado lo que hoy llamamos una marca comercial. A diferencia de otros productos comerciales que necesitan el gentilicio, al nuevo producto musical le bastaba con eso, ser habanero».

Empezó a circular fuera de Cuba. A partir de 1840 se escribieron, cantaron y bailaron habaneras en México, en Venezuela, en Puerto Rico, en otros muchos lugares de América y, sobre todo en España aun cuando no lo escribe un cubano, sino un vasco, Sebastián Yradier. Escribe La paloma en 1860… «Cuando salí de La Habana, válgame Dios». Y afirma Yradier en el verso subsiguiente: «Nadie me ha visto salir, si no fui yo» No era necesario estar en Cuba para escribir una habanera. Muchas de ellas se escribieron sin que sus autores pusieran un pie jamás en la Isla. Pero si Yradier estuvo o no estuvo es secundario, meramente anecdótico. No le resta fuerza a la popularidad de su Paloma, que se sigue cantando como un standard de la música cubana.

..Otras dos habaneras alcanzaron tanta fama como La paloma… Me refiero a El arreglito, del propio Yradier, y O sole mío, del maestro Di Capua; otro standard de la música popular internacional. Bizet usó El arreglito para la famosa habanera de su ópera Carmen. También se emparentaron la zarabanda y la chacona. Chabrier, Debussy, Ravel, Fauré y Saint Saens se valieron de la habanera. Laparra compuso una ópera con ese nombre, La habanera. Albéniz y Falla la cultivan en España. Aparece en zarzuelas. Es obligado aquí mencionar el nombre del matancero José White. Luego de una etapa ritual en París, triunfa en Europa de manera rotunda. Escribe La bella cubana, la más bella de las habaneras.

Agencies/Ciro Bianchi/Diaz Ayala/Internet Photos/YouTube/ Arnoldo Varona/ TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.

> NOTES ON THE ORIGINS of the Cuban Music and its International Repercussions. Video. + BREVES NOTAS sobre los orígenes de la música cubana y su repercusión internacional.

> NOTES ON THE ORIGINS of the Cuban Music and its International Repercussions. Video. + BREVES NOTAS sobre los orígenes de la música cubana y su repercusión internacional.