Quiet and repressed, waiting for another revolutionary effort, the Cuban capital live on July 27, 1892, when the famous Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío disembarked from the Steamer “Mexico”. He arrived in transit to Spain, as representative of Nicaragua, to the celebrations for the fourth centenary of Columbus’ discovery of American lands. In the editorial office of El País, Rubén Darío and Julián del Casal shook hands, who knew each other -through the post office- since 1887, through the pages of the magazine La Habana Elegante, which the Nicaraguan poet received with some frequency and in which they appeared works of both.

El Fígaro offered a banquet to Darío, who was attended by Casal, Enrique Hernández Miyares (who in the issue of July 31, 1887 published an article on Darío in La Habana Elegante), Manuel Serafín Pichardo and others. One of the diners of that noon, Raoul Cay -redactor of El Figaro- says that “Casal barely had lunch, the admiration he feels for Ruben and the joy of having him close, they took away the appetite of the somber poet of” Nieve “».

The Havana days of Darío passed in continuous walks, gatherings, entertainments and raids. When leaving, on the afternoon of July 30, he left a trail of charm among the Cuban intelligentsia.

On December 5 of that same year, back to Spain in the ship Alfonso XIII, Darío made another stop, only a few hours, because the next day he embarked in Mexico, the same one that brought him the first time. He took the opportunity to leave some unpublished texts in the writing of El Fígaro.

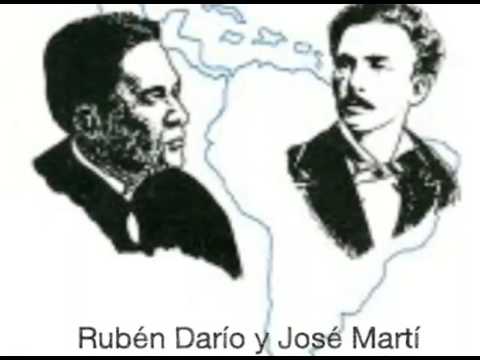

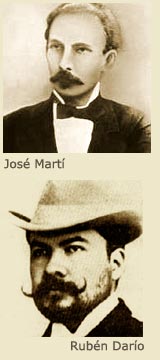

In 1893, in New York, Darío is presented to José Martí, for whom he feels deep respect. Martí had the courtesy to invite him to the evening that was held in Hardman Hall, where he would speak. Upon hearing it, Darío’s admiration for the Cuban thinker and politician is increased.

It is worth reading what Darío wrote of the emotional and unique encounter held with Martí in New York in his Autobiography with which he “wrote profuse prose, full of vitality and color, plasticity and music”; We went through a dark passage; and, suddenly, in a room filled with light, I found myself in the arms of a small man with a body, an enlightened face, a sweet and domineering voice at the same time and who told me this one word: son! The distances were saved forever and Darío with nobility and humility would recognize the leadership of the Cuban poet and revolutionary.

Following the example of José Martí (1852-1895), another modernist poet (who also led the national liberation movement in Cuba against Western colonialism), Darío modernist texts interwoven with thematic references to anti-imperialism and racial harmony only possible in a post-colonial future. An exemplary and still not very well-known poem in that order of ideas can be found in Darío Cantos de vida y esperanza (1905), in an article entitled “A Roosevelt”. In it, he challenged the United States, as “The future invader of naive America That has indigenous blood” (“the future invader of naive America which has indigenous blood”). As such, the colossus of the North, with its cynical fusion of the cult of Hercules and the cult of money, was critically contrasted with the other Americas, “our America, which had poets / from the old times of Netzahualcoyotol”.

Martí wrote in the prestigious Buenos Aires newspaper since 1882, when Bartolito Miter incorporated him as a correspondent, it was in the pages of La Nación where Darío began to taste the lyricism of Martian prose and where he also began the cult, passion and devotion to the figure of the Cuban poet.

Months before the death of the Cuban poet, Darío published “La insurrección en Cuba” (The insurrection in Cuba), where he exalted the patriotic, revolutionary values and the high moral and aesthetic carat of which, with his fiery speeches made his eyes twinkle, purse his lips and creak. heart, “He is the Amazonian writer … the richest writer in the Spanish language, he is the Vanderbilt of our letters”. Before, in 1892 he had dedicated “La risa” to José Martí.

In the obituary, under the title of José Martí, it is not the Father who reproaches the son, but the son, as Martí called him, who recriminates the Father: “And now, teacher and author and friend, forgive us for holding you resentment those who loved and admired you, for having gone to expose the treasure of your talent … Cuba may be late in fulfilling you as it should. American youth greets you and cries; but, oh master, what have you done! It is interesting to point out Ruben’s claim to the dead poet who, as a wizarding king, allowed himself to be dragged by the deceitful star towards the darkest death, because this is where Darío overpowers Art over the country, and where, according to Susana Zanetti, they are strong links with the portrait that Darío de Ibsen makes, the visionary of the snow, and also in my opinion where Darío assumes the I-Poetic, product of his own personal experience. “His homeland, like all the homelands, was a thick comadre who gave broomsticks to his prophet” (Ibsen, Los Raros).

In 1911, Darío, to settle debts, makes an extensive analysis of the work of Martí, one of the most extensive dedicated to a poet, four long essays are sent to La Nación under the title the first three of “José Martí, Poeta” which are published on May 29, June 3 and 10, and the fourth essay under the name of “Free Verses” published on July 8, in them makes a complete, careful and rigorous analysis of one and each of the works, his verses and prose, even his prologues, pointing out, criticizing, reflecting and certifying the quality of Marti’s rich literary production, to end up recognizing that it was not he who contributed the germ plasm of the modernist swan nor the celestial grains of his doctrine: “That Archangel with a steel breastplate was seen at that time, in New York and in Washington, the wings of a swan”.

DEL POETA NICARAGUENSE RUBÉN DARÍO Y SU ADMIRACIÓN POR EL REVOLUCIONARIO CUBANO JOSÉ MARTÍ.

Tranquila y reprimida se mantenía la capital Cubana ese 27 de julio de 1892, al desembarcar del vapor “México” el afamado poeta Nicaraguense Rubén Darío. Llegaba en tránsito hacia España, como representante de Nicaragua, a los festejos por el cuarto centenario del descubrimiento de Colón de tierras americanas. En la redacción del periódico El País se estrecharon las manos Rubén Darío y Julián del Casal, quienes se conocían -gracias al correo- desde 1887, a través de las páginas de la revista La Habana Elegante, que el poeta nicaragüense recibía con cierta frecuencia y en la que aparecieran trabajos de ambos.

El Fígaro ofreció un banquete a Darío, al cual asistieron Casal, Enrique Hernández Miyares (que en el número del 31 de julio de 1887 publicara un artículo sobre Darío en La Habana Elegante), Manuel Serafín Pichardo y otros. Uno de los comensales de aquel mediodía, Raoul Cay -redactor de El Fígaro- cuenta que «Casal apenas almorzó, la admiración que siente por Rubén y el regocijo de tenerlo cerca, quitaron el apetito al sombrío poeta de “Nieve” ».

Los días habaneros de Darío transcurrieron en continuos paseos, tertulias, agasajos y correrías. Al partir, en la tarde del 30 de julio, dejaba una estela de encanto entre la intelectualidad cubana.

El 5 de diciembre de aquel mismo año, de regreso a España en el buque Alfonso XIII, Darío hizo otra escala, de solo unas horas, pues al día siguiente embarcó en el México, el mismo que lo trajo la primera vez. Aprovechó para dejar algunos textos inéditos en la redacción de El Fígaro.

En 1893, en Nueva York, Darío es presentado a José Martí, por quien siente profundo respeto. Martí tuvo la gentileza de invitarlo a la velada que se celebró en Hardman Hall, donde él hablaría. Al escucharlo, se acrecienta la admiración de Darío hacia el pensador y político cubano.

Cabe leer lo que escribiera Darío del emotivo y único encuentro sostenido con Martí en Nueva York en su Autobiografía con el que ‟escribía una prosa profusa, llena de vitalidad y de color, de plasticidad y de música”; Pasamos por un pasadizo sombrío; y, de pronto, en un cuarto lleno de luz, me encontré entre los brazos de un hombre pequeño de cuerpo, rostro de iluminado, voz dulce y dominadora al mismo tiempo y que me decía esta única palabra: ¡hijo! Las distancias quedaron guardadas para siempre y Darío con nobleza y humildad reconocería el liderazgo del poeta y revolucionario cubano.

Siguiendo el ejemplo de José Martí (1852-1895), otro poeta modernista (quien también dirigió el movimiento de liberación nacional en Cuba contra el colonialismo occidental), Darío textos modernistas entretejió con referencias temáticas al anti-imperialismo y la armonía racial solamente posible en un futuro post-colonial. Un ejemplar y todavía no muy conocido poema en ese orden de ideas se encuentra en Darío Cantos de vida y esperanza (1905), en un artículo titulado “A Roosevelt”. En ella, él desafió a Estados Unidos, como “El Futuro invasor de la América ingenua Que tiene sangre indígena” (“el futuro invasor de la América ingenua la que tiene sangre indígena”). Como tal, el coloso del Norte, con su fusión cínica del culto de Hércules y el culto al dinero, fue contrastada críticamente con las otras Américas, “la América nuestra, Que tenia poetas / desde los viejos Tiempos de Netzahualcoyotol”.

Martí escribía en el prestigioso diario bonaerense desde 1882, fecha en que Bartolito Mitre lo incorporó como corresponsal, fue en las páginas de La Nación donde Darío comenzó a degustar del lirismo de la prosa martiana y donde tambien iniciara el culto, pasión y devoción por la figura del poeta cubano.

Meses antes de la muerte del poeta cubano, Darío publica ‟La insurrección en Cuba”, donde exalta los valores patrióticos, revolucionarios y el alto quilataje moral y estético del que, con sus encendidos discursos hacía centellear los ojos, fruncir los labios y crujir el corazón, ‟ Es el escritor amazónico… el escritor más rico en lengua española, es el Vanderbilt de nuestras letras”. Antes, en 1892 le había dedicado ‟La risa” a José Martí.

En la necrológica, bajo el título de José Martí no es el Padre quien recrimina al hijo, sino el hijo, puesto que así lo llamó Martí, quien recrimina al Padre: ‟Y ahora, maestro y autor y amigo, perdona que te guardemos rencor los que te amábamos y admirábamos, por haber ido a exponer el tesoro de tu talento…Cuba quizá tarde en cumplir contigo como debe. La juventud americana te saluda y te llora; pero, ¡oh maestro, qué has hecho! Se hace interesante puntualizar el reclamo que le hace Rubén al poeta muerto quien como rey mago se dejó arrastrar por la estrella engañosa hacia la más negra muerte, porque aquí es donde sobrepone Darío al Arte sobre la patria, y donde según Susana Zanetti se encuentran fuertes vínculos con el retrato que hace Darío de Ibsen, el visionario de la nieve, y también a mi juicio donde Darío asume el Yo-Poético, producto de su propia vivencia personal. ‟ su patria, como todas las patrias, fue una espesa comadre que dio de escobazos a su profeta” (Ibsen, Los Raros).

En 1911, Darío, para saldar deudas, realiza un análisis extenso a la obra de Martí, uno de los más extenso dedicado a un poeta, cuatro largos ensayos son enviados a La Nación bajo el Título los primeros tres de ‟José Martí, Poeta” los cuales se publican el 29 de Mayo, 3 y 10 de Junio, y el cuarto ensayo bajo el nombre de ‟Versos libres” que se publica el 8 de julio, en ellos hace un análisis completo, cuidadoso y riguroso de una y cada una de las obras, sus versos y prosas, hasta sus prólogos, puntualizando, criticando, reflexionado y certificando la calidad de la rica producción literaria de Martí, para terminar reconociendo que no fue él quien aportó el plasma germinal del cisne modernista ni los granos celestes de su doctrina: ‟A aquel Arcángel de coraza de acero, se le vieron en ese tiempo, en Nueva York y en Washington alas de cisne”.

Agencies/CubaLiteraria/Depestre/Amaya/Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.

> NICARAGUAN POET RUBÉN DARÍO and his Admiration for Cuban Revolutionary José Martí. <> DEL POETA NICARAGUENSE RUBÉN DARÍO y su admiración por el Revolucionario Cubano José Martí.

> NICARAGUAN POET RUBÉN DARÍO and his Admiration for Cuban Revolutionary José Martí. <> DEL POETA NICARAGUENSE RUBÉN DARÍO y su admiración por el Revolucionario Cubano José Martí.