HISTORICAL SPANISH MEMORIES ABOUT OUR FAMOUS DRINK “CUBA LIBRE”

HISTORICAL SPANISH MEMORIES ABOUT OUR FAMOUS DRINK “CUBA LIBRE”

Put yourself in situation: War of the Ten Years, Cuba, 1870.

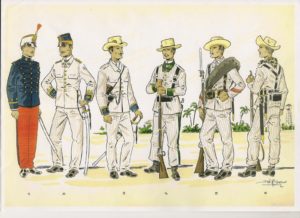

The Spanish army tries to maintain the peninsular dominion over the colony and fights with the arm of the island pro-independence forces. The skirmishes follow one another and both sides sweat under the tropical sun. The Cuban rebels and their freed slaves drink native-name mejunjes such as agua mona, frucanga, punch mambí, sambumbia (fermented water and cane honey) or canchánchara (water, honey, mint and cane liquor), while the Spaniards cast from time to time a drink of Bacardi rum, created eight years before by the Catalan Facundo Bacardi in Santiago de Cuba. All these concoctions infuse heat and courage in the combatants, especially in the mambises who spend the day screaming alive to Cuba Libre and die to Spain.

The writer and soldier Cesáreo Fernández Duro (1830-1908) would later tell in his work ‘Venturas y misfortunes’ (1878) that, in honor of his war cry, the Cuban rebels called “free Cuba” water with sugar, a name that he also received the water with slightly embolingante honey that the Spaniards captured by the enemy drank from time to time. No wonder then that in 1900 he received the same nickname a drink made with rum and a new sweet syrup based on cola nut and coca extract that the Americans were fond of. Yankee Coca-Cola and Cuban white rum were mixed in August 1900 in a bar in Havana, a usual refuge for US military personnel stationed there after the war. Captain Charles V. Russell used to drink cola with Bacardi, a combination that for lack of name received the “free Cuba” by popular acclaim among those attending.

Unlike so many other stories related to gastronomy, it has all the signs of being true. Charles Russell was real, just like Fausto Rodríguez, an eyewitness to the baptism of Cuba Libre and who years later would tell the story. The combination quickly became popular among Americans residing in Cuba, and a few years later it jumped to Europe thanks to the international expansion of brands such as Coca-Cola or Pepsi Cola.

https://youtu.be/anuXQ_TfGLo

In 1937 the formula of Cuba Libre appeared in the book of the Cuban-Spanish bartender Salvador Trullols, along with the recipe of ‘Free Spain’, a version with brandy instead of rum. And in the 40s it would triumph among the high society of our country, the one that frequented the exclusive premises of Perico Chicote or Jacinto Sanfeliú. Castro’s revolution did the rest and in the 60s, asking for a free Cuba turned into a trend and almost, almost, again into a war cry. So famous was it that it gave rise to the birth of a word that now includes all the combinations of spirits with soda, the cubata.

HISTÓRICOS RECUERDOS ESPAÑOLES SOBRE NUESTRA FAMOSA BEBIDA “CUBA LIBRE”

HISTÓRICOS RECUERDOS ESPAÑOLES SOBRE NUESTRA FAMOSA BEBIDA “CUBA LIBRE”

Pónganse ustedes en situación: Guerra de los Diez Años, Cuba, 1870.

El ejército español intenta mantener el dominio peninsular sobre la colonia y lucha a brazo partido contra los independentistas isleños. Las escaramuzas se suceden y ambos bandos sudan a chorretones bajo el sol tropical. Los rebeldes cubanos y sus esclavos liberados beben mejunjes de nombre nativo como agua mona, frucanga, ponche mambí, sambumbia (fermentado de agua y miel de caña) o canchánchara (agua, miel, hierbabuena y aguardiente de caña), mientras que los españoles echan de vez en cuando un trago de ron Bacardí, creado ocho años antes por el catalán Facundo Bacardí en Santiago de Cuba. Todos estos brebajes infunden calor y ánimo en los combatientes, sobre todo en los mambises que se pasan el día gritando vivas a la Cuba libre y mueras a España.

El escritor y militar Cesáreo Fernández Duro (1830-1908) contaría después en su obra ‘Venturas y desventuras’ (1878) que, en honor a su grito de guerra, los rebeldes cubanos llamaban «cuba libre» al agua con azúcar, nombre que también recibió el agua con miel ligeramente embolingante que bebían de vez en cuando los españoles capturados por el enemigo. No es de extrañar pues que en 1900 recibiera el mismo apodo una bebida hecha con ron y un novedoso jarabe dulzón a base de nuez de cola y extracto de coca al que eran aficionados los estadounidenses. La Coca-Cola yanqui y el ron blanco cubano se mezclaron en agosto de 1900 en un bar de La Habana, refugio habitual del personal militar norteamericano estacionado allí después de la guerra. El capitán Charles V. Russell solía tomar refresco de cola con Bacardí, combinación que a falta de nombre recibió el de «cuba libre» por aclamación popular entre los allí asistentes.

A diferencia de tantas otras historias relacionadas con la gastronomía, ésta tiene todos los visos de ser verdadera. Charles Russell fue real, igual que Fausto Rodríguez, testigo presencial del bautizo del cuba libre y quien años después relataría el suceso. El combinado se popularizó rápidamente entre los estadounidenses residentes en Cuba, y pocos años después saltó a Europa gracias a la expansión internacional de marcas como Coca-Cola o Pepsi Cola.

En 1937 apareció la fórmula del cuba libre en el libro del barman cubano-español Salvador Trullols, junto con la receta del ‘España libre’, una versión con brandy en vez ron. Y en los años 40 triunfaría entre la alta sociedad de nuestro país, aquella que frecuentaba los exclusivos locales de Perico Chicote o Jacinto Sanfeliú. La revolución de Castro hizo el resto y en los 60, pedirse un cuba libre se convirtió en tendencia y casi, casi, de nuevo en un grito de guerra. Tan famoso se hizo que dio pie al nacimiento de una palabra que engloba ahora a todos los combinados de espirituoso con refresco, el cubata.

Agencies/Sur/Ana Vega Perez/Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.