DE NUESTRAS TRADICIONES: “LOS VELORIOS” EN LA CUBA DE AYER.

DE NUESTRAS TRADICIONES: “LOS VELORIOS” EN LA CUBA DE AYER.

En Cuba, la costumbre de velar un cadáver viene de atrás, es decir, de España y África y es tan vieja entre nosotros que ya en una de nuestras primeras publicaciones literarias, El Papel Periódico de La Habana, en su edición correspondiente al 4 de diciembre de 1804, aparece un “Extracto de lo que suele acontecer en los velorios”. Cuenta su autor que un día, frente a una casa donde se velaba un cadáver, uno de los amigos del muerto, para animarlo a entrar, se le acercó y le dijo: “Pase usted a divertirse, que para todos hay y para más que vengan”.

Quizás aquí sea conveniente precisar que, a diferencia de lo que sucede en las ciudades, en los campos cubanos velorio no es sinónimo de mortuorio. Nuestros campesinos velan a un santo, y no precisamente en su día, por agradecimiento o en pago de una promesa. O velan a un cerdo mientras se asa en púa y en ambos casos hay música y baile y corre la bebida. Ya en 1875, Esteban Pichardo, en su Diccionario provincial casi razonado de voces y frases cubanas, afirma que velorio es “la acción y efecto de velar en reunión a una persona difunta o próxima a morir… Si el cadáver es de algún niño perteneciente a la gentualla, el velorio se convierte en diversión. En La Habana vulgar también hay velorios de mondongo, lechón asado, etc., conforme sea el sustituto del difunto para cenar muy tarde, beber, bailar…” Dice además: “La noche pasa en conversación a voz baja, intercalándose más tarde sus golosinas, café y otras bebidas”.

Porque si en los velorios de hoy se ve pasar a veces una botella de ron, y más de una también, solo por espantar el pesar y no por otra cosa, desde luego, comer era práctica habitual en los velorios de antaño.

MIS RECUERDOS…

Antes en nuestro país en verdad un velorio era lo que se puede decir…un velorio. Un acto revestido de solemnidad aunque no faltase en ninguno de ellos el chistoso de guardia a quien los reunidos escuchaban sus pujos a falta de algo más interesante que hacer. Entonces, tan pronto se conocía la noticia de la muerte de un conocido, amigos y vecinos se aprestaban a “cumplir” con el difunto.

Las mujeres vestían de negro y aquel que andaba siempre en mangas de camisa casi agradecía la oportunidad para volver a lucir el traje que se compró cuando el bautizo de la niña y que no usaba desde que ella cumpliera los 15, pero que bien cepillado volvía a quedar como nuevo. Un trajecito de apéame uno, pero que todavía daba el plante con la corbata de listas, que era la única. O la guayabera de hilo, con la infaltable corbata de mariposa, muy cómoda porque venía de fábrica con el lazo hecho y bastaba con sujetarla al cuello con sus presillas, que también eran de fábrica.

En ese tiempo, “por cumplir”, la gente se pasaba la noche entera en la funeraria, aunque tuviera que escucharle una y otra vez a los dolientes el relato pormenorizado de los días pasados en el hospital, la lenta agonía y los esfuerzos vanos del médico por prolongarle la vida. Menudeaban frases como “no somos nada” y otras que recordaban lo efímero de la existencia y no era raro que alguien aludiera una y otra vez a lo vivito y coleando que andaba el difunto antes de morirse. Los familiares no reprimían los recuerdos ni las lágrimas ante cada expresión de pésame que se acompañaban con besos, abrazos y sonoros manotazos en las espaldas y el silencio y la tranquilidad del lugar se rompían de cuando en cuando con manifestaciones de dolor mal contenidas. Desmayos. Subidas de presión. Calmantes, tazas de café y juguitos. Cuando los funerarios se disponían a llevarse el ataúd uno o más familiares se abrazaban a la caja como si abrazaran al muerto mismo. “No, no se lo lleven”, decían a voz en cuello. Pero era la hora y había que llevárselo.

No era lo mismo un velorio en la funeraria Caballero que en las de Maulini o en Fiallo. Pobres y ricos seguían divididos al borde de la tumba. Y en la tumba misma. La muerte tenía también rango y clase y el servicio fúnebre se pagaba en consecuencia. Existía el término medio, que era el que brindaba la funeraria Nacional. Los funerarios de medio pelo o sus agentes recorrían clínicas y hospitales para enterarse de quién en ellos estaba a punto de fallecer e ir enamorando a los familiares a fin de que no se les escapara el negocio. Un negocio que se disputaban en ocasiones ante un cuerpo todavía caliente. Pese a las diferencias y aunque el muerto no protestara, lo mismo daba un velorio en Rivero que en Luyanó o en Oliva: el entierro no salía hasta que no se pagara el funeral. No valían súplicas ni promesas. Y había zonas en el cementerio. Según la ubicación de la bóveda, así era la posición económica del muerto. Una necrópolis que reproducía en sus cuadros y en el lujo de los panteones la ciudad de los vivos, con su Country Club, su Miramar, su Vedado, su Llega y Pon…

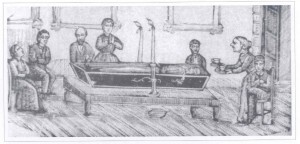

Nunca he visto comer en un velorio, y quizás vuelvan ahora las apetecidas tazas de chocolate, pero sí asistí de niño a algunos que tuvieron lugar en la propia vivienda del difunto. Se contrataban los servicios de una casa fúnebre, que ponía el ataúd, las velas, el crucifijo y el carro, y los dolientes pedían sillas prestadas entre los vecinos. En los años 20 y 30 hubo en La Habana un funerario célebre en lo que al velorio casero se refiere. Se apellidaba Raola. Ya desde mucho antes existían funerarias en esta capital. Caballero, por ejemplo, se fundó en 1857, en Centro Habana, y allí estuvo hasta que en los años 40 o quizás antes se trasladó para de 23 y M, que no era entonces la esquina céntrica que sería después. Y ya que sobre esto hablamos, recuerdo la ocasión en que en Santiago de Cuba, sin tener donde dormir, pasé toda una noche, con mis bártulos de reportero errante y casi vagabundo, en la funeraria Bartolomé.

No digo que el dolor por la pérdida de un ser querido sea menor, pero la muerte, “algo que diariamente pasa”, se ve de otra manera. Hoy los velorios se han simplificado. A veces no duran las 24 horas que antes se hacían de rigor. Palabra esa exacta para una mala noche. Son pocos los que pasan la noche completa junto a un muerto pues con el pretexto del transporte, “que está pésimo”, o de compromisos ineludibles en la mañana siguiente, a las once, a más tardar, empieza la desbandada. De los que “cumplieron” porque muchos se hacen el chivo loco y ni por la funeraria se portan por estrecha que fuera su amistad con el muerto.

FROM OUR TRADITIONS: “LOS VELORIOS” IN YESTERDAY’S CUBA.

FROM OUR TRADITIONS: “LOS VELORIOS” IN YESTERDAY’S CUBA.

In Cuba, the custom of watching a corpse (A “Velorio”) comes from behind, that is, from Spain and Africa and is so old among us that already in one of our first literary publications, The Newspaper of Havana, in its edition corresponding to 4 December 1804, there is an “Excerpt of what usually happens at wakes.” His author says that one day, in front of a house where a corpse was watched, one of the dead man’s friends, to encourage him to enter, approached him and said: “Come to have fun, for all there is and for more than come. ”

Perhaps here it is convenient to specify that, unlike what happens in the cities, in the Cuban fields, velorio is not synonymous with mortuary. Our peasants watch over a saint, and not precisely in his day, by gratitude or in payment of a promise. Or they watch a pig while it is roasted on a spike and in both cases there is music and dancing and the drink runs. Already in 1875, Esteban Pichardo, in his provincial Dictionary almost reasoned of Cuban voices and phrases, affirms that wake is “the action and effect of watching in meeting a dead person or next to die … If the corpse is of some child belonging to the gentualla, the wake becomes fun. In La Habana vulgar there are also wakes of mondongo, roasted piglet, etc., as the substitute of the deceased to dine very late, drink, dance … “He also says:” The night passes in conversation in a low voice, interspersed later your treats , coffee and other drinks. ”

Because in today’s wakes you can sometimes see a bottle of rum, and more than one too, just to scare the grief and not for anything else, of course, eating was usual practice in the wakes of yesteryear.

MY MEMORIES…

Before in our country in truth a wake was what can be said … a wake. An act covered with solemnity, although the humorous guard on whom the assembled listened to their bids for lack of something more interesting to do was not lacking in any of them. Then, as soon as the news of the death of an acquaintance was known, friends and neighbors prepared to “comply” with the deceased.

The women dressed in black and the one who was always in shirt sleeves was almost grateful for the opportunity to show off the suit that was bought when the christening of the girl and that she had not worn since she turned 15, but that well brushed returned to look like new A suit of apéame one, but that still gave the plant with the list tie, which was the only one. Or the yarn guayabera, with the inevitable butterfly tie, very comfortable because it came from the factory with the bow made and it was enough to fasten it to the neck with its clips, which were also from the factory.

At that time, “to be fulfilled”, people spent the entire night in the funeral home, even though they had to listen to the mourners over and over again, the detailed account of the days spent in the hospital, the slow agony and the futile efforts of the doctor for prolonging his life. They commented on phrases such as “we are nothing” and others that remembered the ephemeral nature of existence and it was not unusual for someone to allude again and again to what the deceased lived and kicked before he died. The relatives did not repress the memories nor the tears before each expression of condolence that was accompanied with kisses, hugs and loud slaps on the backs and the silence and tranquility of the place broke from time to time with manifestations of pain badly contained. Fainting. Pressure rises. Calming, coffee cups and juices. When the undertakers were preparing to take the coffin, one or more relatives would hug the box as if they were hugging the dead man himself. “No, do not take it,” they said loudly. But it was time and it had to be taken away.

A “Velorio” at the Caballero funeral home was not the same as in Maulini’s or Fiallo’s. Poor and rich were still divided on the edge of the grave. And in the grave itself. Death also had rank and class and the funeral service was paid accordingly. There was the middle term, which was the one provided by the National Funeral Home. The funeral of half hair or his agents ran through clinics and hospitals to find out who was about to die and to fall in love with family members so that they do not run out of business. A business that was sometimes disputed before a body still hot. Despite the differences and although the dead did not protest, the same gave a wake in Rivero than in Luyanó or Oliva: the funeral did not leave until the funeral was paid. They were not worthy of supplications or promises. And there were areas in the cemetery. According to the location of the vault, this was the economic position of the deceased. A necropolis that reproduced in its paintings and in the luxury of the pantheons the city of the living, with its Country Club, its Miramar, its Vedado, its Arrives and Pon …

I have never seen eating at a wake, and perhaps the desired cups of chocolate will come back now, but I did attend as a child some that took place in the deceased’s own home. The services of a funeral house were contracted, that put the coffin, the candles, the crucifix and the car, and the mourners asked for borrowed chairs between the neighbors. In the 20s and 30s, there was a famous funeral home in Havana as far as home visitation is concerned. It was called Raola. Since long before there were funeral homes in this capital. Caballero, for example, was founded in 1857, in Centro Habana, and there he stayed until in the 40s or perhaps before he moved to 23 and M, which was not then the central corner that would be after. And since we are talking about this, I remember the occasion when, in Santiago de Cuba, without having a place to sleep, I spent a whole night, with my bag of errant and almost vagabond reporter, at Bartolomé Funeral Home.

I do not say that the pain for the loss of a loved one is minor, but death, “something that happens daily,” is seen in another way. Today the wakes have been simplified. Sometimes they do not last the 24 hours that before were done of rigor. Word that exact for a bad night. There are few who spend the whole night with a dead person because, under the pretext of transportation, “that is terrible”, or of unavoidable commitments on the following morning, at eleven o’clock, at the latest, the disbanding begins. Of those who “fulfilled” because many become the crazy goat and neither for the funeral they behave no matter how close their friendship with the dead.

Agencies/Ciro Bianchi/Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.