THE POLIMITA, THE MOST BEAUTIFUL SNAIL OF THE WORLD, IN DANGER OF EXTINCTION IN CUBA.

THE POLIMITA, THE MOST BEAUTIFUL SNAIL OF THE WORLD, IN DANGER OF EXTINCTION IN CUBA.

The polimitas, endemic to Cuba, which is considered the most beautiful snail in the world and whose shell owns extraordinary brightness, in terms of its shape and colors is in danger of extinction in Cuba.

These mollusks, with a ventral fleshy foot that they use to crawl, are located in the intricate regions of eastern Cuba, especially in the municipalities of Baracoa and Maisí in the province of Guantanamo, although they can also be found in adjoining areas of the territory and Neighbor Holguin.

These organisms have become local assets, not only because of their well-known beauty throughout the world, but also because of their function as biological control of fungi and lichens harmful to plants. According to studies, four adult polyimitas are enough on a coffee plant to keep their leaves free of fungi. Six or eight have the same function in a guava tree.

The naturalists recognize the presence of six species (polymita venusta, picta, muscarum, sulphurosa, versicolor and brocheri).

In the case of the picta, the one with the most vivid colorations, it is considered a National Snail and covers five subspecies.

However, a recent monitoring by Cuban scientists reports the danger of extinction of the polymita sulphurosa, when counting the few specimens of that species that remain in the mountainous region of Sagua de Tánamo and Moa, in northeastern Holguín.

The marked microlocalization of the commonly known sulfur-colored polymita, endemic to that area, and its relatively low dispersion capacity, determine, among other factors, that its populations have been considerably reduced in recent years, according to experts from the Antonio Nuñez Jiménez Foundation. Nature and Man

These molluscs have arboreal habits, feed on fungi and lichens and are sensitive to changes in humidity, luminosity, temperature and salinity of the environment, so they have not been able to adapt to other territories. They are considered the symbol of the fauna of Baracoa.

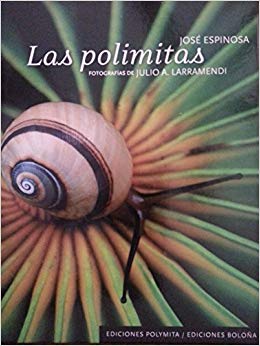

Studies collected in the book Las Polimitas, by José Espinosa, PhD in Biological Sciences and principal investigator of the Institute of Oceanology, and the renowned photographer Julio Larramendi, corroborate the growing decrease in populations. Among the causes pointed out the looting of their shells for sale, collecting or crafts. Added to this factor is the loss or transformation of the natural habitat, the introduction of exotic plants and animals that compete for their environment, and in recent times climate change, which causes the reduction of rainfall and the increase in temperatures.

And although the capture of the invertebrate is prohibited in Cuba and there are regulations for it, the descent caused by the international demand of collectors is alarming. Cuba signed an agreement to keep the Cuban Polymath safe, within the legal framework of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Appendix I of the Cites included, at the proposal of Cuba, the adoption of strict measures for traffickers of these endemic molluscs from the east of the country.

They are also declared “special” of our country, with maximum protection and the prohibition to extract them from their environment, export them or commercialize them, under the protection of a resolution of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment.

LA POLIMITA, EL CARACOL MÁS BELLO DEL MUNDO, EN PELIGRO DE EXTINCIÓN EN CUBA.

LA POLIMITA, EL CARACOL MÁS BELLO DEL MUNDO, EN PELIGRO DE EXTINCIÓN EN CUBA.

La polimita, endémica de Cuba, que está considerada el caracol más bello del mundo y cuya concha es dueña de extraordinaria vistosidad, en cuanto a su forma y colores está en peligro de extinción en Cuba.

Esos moluscos, con pie carnoso ventral del que se valen para arrastrarse, se localizan en las regiones intrincadas del oriente cubano, especialmente en los municipios de Baracoa y Maisí de la provincia de Guantánamo, aunque también pueden hallarse en zonas colindantes del propio territorio y del vecino Holguín.

Estos organismos han devenido patrimonios locales, no solo por su vistosidad conocida en todo el orbe, sino también por su función de control biológico de hongos y líquenes perjudiciales a las plantas. Según estudios, bastan cuatro polimitas adultas sobre una planta de café para mantener sus hojas libres de hongos. Seis u ocho cumplen igual función en un árbol de guayaba.

Los naturalistas reconocen la presencia de seis especies (polymita venusta, picta, muscarum, sulphurosa, versicolor y brocheri).

En el caso de la picta, la de coloraciones más vivas, está considerada Caracol Nacional y abarca cinco subespecies.

Sin embargo, un reciente monitoreo realizado por científicos cubanos reporta el peligro de extinción de la polymita sulphurosa, al contabilizar los pocos ejemplares de esa especie que quedan en la región montañosa de Sagua de Tánamo y Moa, en la nororiental Holguín.

La marcada microlocalización de la comúnmente conocida polymita color azufre, endémica de esa zona, y su relativa baja capacidad de dispersión determinan, entre otros factores, que sus poblaciones se hayan reducido considerablemente en los últimos años, según expertos de la Fundación Antonio Nuñez Jiménez de la Naturaleza y El Hombre.

Estos moluscos tienen hábitos arborícolas, se alimentan de hongos y líquenes y son sensibles a los cambios de humedad, luminosidad, temperatura y salinidad del ambiente, por lo que no ha podido adaptarse a otros territorios. Se consideran el símbolo de la fauna de Baracoa.

Estudios recogidos en el libro Las Polimitas, de José Espinosa, doctor en Ciencias Biológicas e investigador titular del Instituto de Oceanología, y el reconocido fotógrafo Julio Larramendi, corroboran la creciente disminución de las poblaciones. Entre las causas señala el saqueo de sus conchas para la venta, coleccionismo o artesanías. A este factor se suma la pérdida o transformación del hábitat natural, la introducción de plantas y animales exóticos que compiten por su entorno, y en los últimos tiempos el cambio climático, causante de la reducción de las lluvias y el aumento de las temperaturas.

Y aunque en Cuba está prohibida la captura del invertebrado y existen regulaciones para ello, es alarmante el descenso originado por la demanda internacional de coleccionistas. Cuba firmó un acuerdo para mantener a salvo a la polimita cubana, en el marco legal de la Convención Sobre el Comercio Internacional de Especies Amenazadas de la Fauna y Flora Silvestre (Cites). El Apéndice I de la Cites incluyó, a propuesta de Cuba, la adopción de severas medidas para traficantes de estos moluscos endémicos del oriente del país.

También están declaradas “especiales” de nuestro país, con máxima protección y la prohibición de extraerlas de su medio, exportarlas o comercializarlas, al amparo de una resolución del Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente.

Agencies/RadioHabana/Guadalupe Yaujar/ Lorena Viñas/ Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.