EL SEMANARIO “ZIG ZAG”: RADIOGRAFÍA DEL HUMOR POLÍTICO CUBANO.

EL SEMANARIO “ZIG ZAG”: RADIOGRAFÍA DEL HUMOR POLÍTICO CUBANO.

Los dictadores nunca han soportado el humor y menos aún a los humoristas. Esa es parte de la historia del Semanario Cubano Zig Zag, que el viejo dictador cubano liquidará en 1960 y también otros periódicos, excepto los dos afines en aquel tiempo ‘Revolución’ y ‘Hoy. Allí se acabó con la libertad de prensa y se terminó con la libertad de expresión en Cuba.

Recordando la historia del humor político en Cuba no se puede hablar sin mencionar al Zig Zag.

HISTORIA DEL HUMOR POLÍTICO.

Cuando llega la noche, los ciudadanos de Inglaterra, Francia, España y hasta en la misma Rusia, se sientan a disfrutar de un programa de humor donde los muñecos representan a sus políticos más cercanos. Esos mismos ciudadanos han visto ya, durante el día, escritos y caricaturas en la prensa donde se satirizan situaciones reales y actuales. Y donde, desde el más sencillo servidor público, hasta el presidente del país o el monarca, han sido reflejados para mofa y satisfacción del hombre común: el ciudadano.

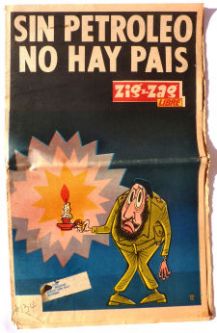

En Cuba no. Antes de que terminara el convulso año de gracia de 1959, el jefe de la triunfante rebelión tomó una de las decisiones radicales que marcarían el futuro de la isla, y de un gobierno personalista durante los siguientes 60 años: cerrar de un plumazo el semanario Zig Zag fundado en 1938, bastión cubano del humor político; heredero de La política cómica, de Ricardo Torriente, y de La semana, de Sergio Carbó, y de una fortísima tradición en las imperfectas democracias anteriores.

Fue el Zig Zag y no otro, el primer diario cerrado por decisión del iracundo rebelde. Su primera plana quedó en el recuerdo de toda una generación que ya Jorge Mañach había retratado en su famoso ensayo Indagación del choteo, y que reflejaba con fina ironía lo que el antiguo abogado, devenido comandante, haría día y noche a lo largo de su vida. El chiste que tan profundamente molestó fue este: “Hace 15 minutos que Fidel no habla”.

Poco después prohibía al actor cómico más popular de Cuba, Leopoldo Fernández (Tres Patines’), porque en una actuación teatral, mientras señalaba hacia un gran retrato del ‘jefe’, dijo: “A éste tenemos que colgarlo bien alto”.

No sería hasta más tarde, justamente al año y cinco meses del triunfo revolucionario, que caería, víctima de los afanes y propósitos totalitarios, el decano de la prensa escrita cubana, el ‘Diario de la Marina’, y la operación de nacionalización terminaría con la apropiación a manos del Estado de todos los medios de prensa, radio y televisión. No solamente moría la libertad de expresión. Habían asesinado el humor político en Cuba.

O tal vez no. Muerto en tanto representación social, y vehículo democrático para la libre expresión, el humor político pasaría, como sucedió en todos los países de corte socialista, a las sombras, replegado a la picaresca popular del boca a boca, a los rincones de la intimidad más profunda, pues el temor de hacer un chiste ‘contrarrevolucionario’ despojaría a ese género popular del brillo de la espontaneidad y de su función catártica.

Dardos sin punta, la sátira quedó descartada como hecho subversivo, limitada a lo oral, que no deja huellas palpables o pruebas materiales. Sobrevivió en la penumbra familiar como pausa y suspiro con los que el cubano buscaba mantenerse independiente, y se debió, en parte, a esa burla crónica que, al decir de Mañach, siempre ha sido una de sus grandes defensas: “Le ha servido de amortiguador para los choques de la adversidad, de muelle para resistir las presiones políticas demasiado gravosas y de válvula de escape para todo género de impaciencias”.

En manos del Estado la prensa y los medios de comunicación, y ese Estado a su vez en manos de una voluntad única, no quedó nada del ejercicio de libre y sano albedrío. La única ventana diminuta para el humor político fue la burla inclemente del pasado, que de tanto ser llevado al presente, perdió el sentido de tiempo ya ido, para convertirse en la máscara del hoy mismo. La realidad fue pareciéndose peligrosamente a lo que nadie recordaba ya. O recordaba solamente a través del choteo.

Fue una máscara. Una mordaza amarga, pero doblez al fin y al cabo. El exterior cumplía con los dictámenes del Estado autoritario. Las segundas lecturas comenzaban rostro adentro. Nació la hipérbole, que es insana, porque está fabricada de espejos, de tortuosos caminos, de retruécanos. De tanto hablar del futuro luminoso se perdieron los ojos. Y la gente común comenzó a preguntarse si el futuro iba a llegar algún día.

Pero hay un pero. Un pero profiláctico. El choteo, el sí de puerta hacia afuera y el no o el tal vez en la sombra, han sido desde entonces el don más preciado del cubano, a contrapelo de lo que advirtió Mañach: “Si se hiperboliza este don, empieza por codiciarse la comodidad vital de la alegría y se puede llegar a exigir ese lujo vital que es la absoluta independencia de toda autoridad”. El choteo clasifica sin ningún inconveniente entre las formas de resistencia.

No puede hiperbolizarse una ideología que bebe directamente del mesianismo y de la liturgia de las religiones. Es imposible que se vaya más allá de las fronteras que dicta en persona el hiperbolizador en jefe. Lo real se hizo representación teatral, entrando en la categoría de irrealidad. La realidad era otra, desconocida por la verdad oficial, sin representación visual en el discurso cotidiano. Era la vida fingida, que te hace sentirte cómplice, actor de un juego de falsas improvisaciones y estudiadas espontaneidades. Y por desgracia fue una suerte.

El chiste no busca subvertir la realidad, sino pervertirla o revertirla momentáneamente. Busca pensamientos afines, solidaridad en la opinión, complicidad en el delirio de la desgracia que nos dicen suerte. En una sociedad socializada, el chiste político deja el amargo pero inigualable y duradero sabor del pecado.

Se es héroe durante 30 segundos. Se sabe que alguien -el inventor o adaptador del chiste- estaba pensando en uno mismo. Se intuye un semejante en la sombra. Queda, entre el miedo fugaz, el regusto de haber traspasado momentáneamente las rejas de lo absoluto. Se ríe porque se duda. Mas, al mismo tiempo, se teme.

Es, de alguna manera, como haberse pasado por un momento al enemigo que luego se sale a combatir entre consignas, con una fe un poco más agujereada. Si el enemigo ríe, entonces no es tan malo como lo pintan. Es la única manera en que la irrealidad se hace real. Lo kafkiano cobra ribetes descarnadamente humanos y peligrosos. No hay ojos, pero sí oídos y bocas.

Cuando llega la noche, los ciudadanos de Inglaterra, Francia, España y hasta en la misma Rusia, se sientan a disfrutar de un programa de humor donde los muñecos representan a sus políticos más cercanos.

En Cuba no. Como muñecos rotos, los cubanos se sientan a reír nueva y viejamente del pasado. Sueñan, en el sueño profundo, con el día en que puedan convertirse en ciudadanos.

THE CUBAN WEEKLY “ZIG ZAG”: RADIOGRAPHY OF CUBAN POLITICAL HUMOR.

THE CUBAN WEEKLY “ZIG ZAG”: RADIOGRAPHY OF CUBAN POLITICAL HUMOR.

Dictators have never endured humor and even less humorists. That is part of the history of the Cuban Zig Zag Weekly, which the old Cuban dictator would liquidate in 1960 and also other newspapers, except the two related at that time ‘Revolution’ and ‘Today. There, freedom of the press was ended and freedom of expression in Cuba was ended.

Remembering the history of political humor in Cuba you can not talk without mentioning the Zig Zag.

HISTORY OF POLITICAL HUMOR.

When the night comes, the citizens of England, France, Spain and even in Russia itself, sit down to enjoy a program of humor where the dolls represent their closest politicians. These same citizens have already seen, during the day, writings and cartoons in the press where real and current situations are satirized. And where, from the simplest public servant, to the president of the country or the monarch, have been reflected to mockery and satisfaction of the common man: the citizen.

In Cuba, no. Before the convulsive year of grace ended in 1959, the head of the triumphant rebellion took one of the radical decisions that would mark the future of the island, and a personalist government for the next 60 years: close the Zig weekly Zag founded in 1938, Cuban bastion of political humor; heir of La política comica, by Ricardo Torriente, and La semana, by Sergio Carbó, and a very strong tradition in the previous imperfect democracies.

It was the Zig Zag and not another, the first newspaper closed by the angry rebel’s decision. His first page remained in the memory of an entire generation that Jorge Mañach had already portrayed in his famous essay “Inquiry into Choteo,” and that reflected with fine irony what the former lawyer, now a commander, would do day and night throughout his life . The joke that so deeply annoyed was this: “Fidel has not spoken for 15 minutes.”

Shortly after it prohibited the most popular comic actor in Cuba, Leopoldo Fernandez (Three Skates’), because in a theatrical performance, while pointing to a large portrait of the ‘boss’, he said: “We have to hang this one high.”

It would not be until later, just a year and five months after the revolutionary triumph, that the dean of the Cuban press, the “Diario de la Marina”, would fall victim to the efforts and totalitarian purposes, and the nationalization operation would end with the appropriation at the hands of the State of all the press, radio and television media. Not only freedom of expression died. They had murdered political humor in Cuba.

Or maybe not. Dead in both social representation, and democratic vehicle for free expression, the political humor would pass, as it happened in all socialist countries, to the shadows, folded back to the popular picaresque from mouth to mouth, to the corners of intimacy more deep, because the fear of making a ‘counterrevolutionary’ joke would strip that popular genre of the brilliance of spontaneity and its cathartic function.

Darts without point, the satire was discarded as a subversive fact, limited to the oral, leaving no palpable traces or material evidence. He survived in the family gloom as a pause and sigh with which the Cuban sought to remain independent, and was due, in part, to that chronic mockery that, according to Mañach, has always been one of his great defenses: “It has served him well shock absorber for the shocks of the adversity, of spring to resist the political pressures too burdensome and of valve of escape for all kinds of impatience “.

In the hands of the State, the press and the media, and that State in turn in the hands of a single will, nothing remained of the exercise of free and healthy will. The only tiny window for political humor was the inclement mockery of the past, which from so much being taken to the present, lost the sense of time already gone, to become the mask of today. The reality was dangerously similar to what nobody remembered anymore. Or remembered only through choteo.

It was a mask. A bitter gag, but fold after all. The exterior complied with the dictates of the authoritarian State. The second readings began face inwards. The hyperbole was born, which is insane, because it is made of mirrors, of tortuous roads, of puns. After so much talk about the bright future, the eyes were lost. And ordinary people began to wonder if the future was going to come some day.

But there is a but. A but prophylactic. The choteo, the yes door to the outside and the no or perhaps in the shade, have been since then the most precious gift of the Cuban, contrary to what Mañach warned: “If this gift is hyperbolized, begin by coveting the the vital comfort of joy and one can come to demand that vital luxury which is the absolute independence of all authority. ” Choteo classifies without any inconvenience among the forms of resistance.

An ideology that drinks directly from messianism and from the liturgy of religions can not be hyperbolized. It is impossible to go beyond the borders dictated in person by the hyperbolize in chief. The real became theatrical representation, entering the category of unreality. The reality was another, unknown by the official truth, without visual representation in everyday discourse. It was the feigned life, which makes you feel complicit, actor of a game of false improvisations and studied spontaneities. And unfortunately it was a luck.

The joke does not seek to subvert reality, but pervert it or reverse it momentarily. Look for related thoughts, solidarity in opinion, complicity in the delirium of misfortune that tell us luck. In a socialized society, the political joke leaves the bitter but unparalleled and lasting flavor of sin.

He is a hero for 30 seconds. It is known that someone – the inventor or adapter of the joke – was thinking of oneself. A similar is sensed in the shadow. There remains, between the fleeting fear, the aftertaste of having momentarily pierced the bars of the absolute. He laughs because he doubts himself. But, at the same time, it is feared.

It is, in some way, like having passed for a moment to the enemy that then goes out to fight between slogans, with a faith a little more bored. If the enemy laughs, then it’s not as bad as they paint it. It is the only way in which unreality becomes real. Kafkaesque takes on starkly human and dangerous edges. There are no eyes, but ears and mouths.

When the night comes, the citizens of England, France, Spain and even in Russia itself, sit down to enjoy a program of humor where the dolls represent their closest politicians.

Agencies/ Internet Photos/ Ramón Fernández/ Arnoldo Varona/ www.TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.