BARES Y TRAGOS DE MI VIEJA HABANA Y SU HISTORIA. VIDEO & FOTOS.

BARES Y TRAGOS DE MI VIEJA HABANA Y SU HISTORIA. VIDEO & FOTOS.

Hagamos un recorrido imaginario de la larga historia de Bares y Tragos de nuestra capital comenzando con una visita historica a “El Floridita” siguiendo por el hoy bar “Vista al Golfo” del Hotel Nacional de Cuba, pasando por el “Sloppy Joe’s”, “Bodeguita del Medio” y “Dos Hermanos”.

Cada uno de esos establecimientos con sus particulares ‘Cuba Libre’ en el Vista al Golfo del Hotel Nacional y Sloppy, mientras que la Bodeguita del Medio y el Floridita con el ‘Mojito’ y el ‘Daiquirí’, el Dos Hermanos ofrece su llamado “Havana Special”.

Es de notar la vigencia de el “Havana Special” ese trago que algunos llaman el Manhattan cubano, una mezcla cuya invención se atribuye a Constantino Ribalaigua, barman catalán radicado en la capital cubana, que se inspiró en una línea de transporte de pasajeros y mercancías que hacía el recorrido Nueva York-Cayo Hueso-La Habana-Nueva York.

LA RUTA NUEVA YORK-CAYO HUESO-LA HABANA-NUEVA YORK.

Desde Nueva York, el tren demoraba dos días en llegar a Cayo Hueso, donde un servicio de ferry-boats, en una travesía de diez horas, transportaba los vagones hasta La Habana. Esa ruta se conoció con el nombre de The Havana Special y posibilitó que Cuba la aprovechara para reafirmarse como importante suministrador del mercado norteamericano. Cruzar el mar sentado cómodamente en un vagón de ferrocarril que antes avanzó sobre la cumbre angosta de una montaña de coral, parece cosa de hadas.

Como las hadas no existen, solo un hombre como el multimillonario Henry Flagler fue capaz de una empresa como esa que extendió la vía férrea hasta Miami y desde allí, de isleta en isleta, la llevó hasta Cayo Hueso para conectar así con Cuba, el resto del Caribe y el Canal de Panamá. De cualquier manera, el 22 de enero de 1912, con la llegada a Cayo Hueso del primer tren procedente de Miami, Flagler hacía realidad su sueño, y ese mismo día embarcaba hacia La Habana a fin de promover su ruta sobre los cayos.

Veintitrés años después, el 2 de septiembre de 1935, un huracán de categoría cinco destruyó parcialmente la infraestructura ferroviaria. Los propietarios de The Havana Special vendieron lo que quedó al estado de Florida. Parte de esas ruinas son todavía visibles. Sobre partes de ellas se erigió la red de carreteras que, desde 1938, une entre sí los cayos floridanos y los enlaza con la península. Desde entonces los ferry no transportaron vagones de ferrocarril.

Prosiguieron su línea de pasajes y carga general y dieron a los viajeros de ambos lados la oportunidad de visitar la orilla contraria con su propio automóvil.

El ferry de Cayo Hueso se interrumpió después de 1959. Hoy, el “Havana Special” es solo el coctel creado por Constantino Ribalaigua, mientras que en el Cayo un busto de Flagler recuerda la historia de su famoso ferrocarril.

El Bar Dos Hermanos, se ubica frente al muelle de The Havana Special y abrió sus puertas en 1892, lo que lo hace uno de los bares más antiguos de la capital cubana. Se caracterizó por su larga barra de madera dura, incompleta desde que hace unos pocos años le cercenaron un pedazo a fin de emplazarlo en uno de los bares del hotel Moka, en Las Terrazas.

Aún así, sigue siendo larga. El poeta español Federico García Lorca frecuentó el Dos Hermanos durante su estancia cubana de 1930, y por allí estuvieron asimismo, entre otros, Alejo Carpentier y Enrique Serpa, autor de novelas como Contrabando y La trampa, y de un cuento antológico, Aletas de tiburón.

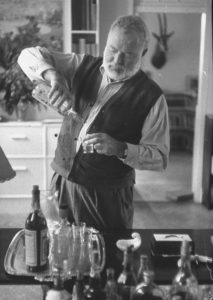

Y, por supuesto, el inevitable Hemingway, que en la festinada opinión de algunos deambuló por todos los bares y cantinas habaneros, aunque centró su preferencia en el Floridita. En Dos Hermanos, «con pasos torpes que lo conducían a una pequeña pero satisfactoria libertad», entró una tarde Andrés, el protagonista de Fiebre de caballos (1988), la novela inicial de Leonardo Padura.

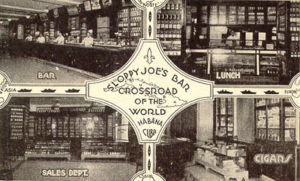

El Floridita fue hasta 1959 el bar más famoso de la ciudad, pero Sloppy Joe’s fue siempre el de más ventas. Supuse que el Sloppy Joe’s de Cayo Hueso antecedió a este de la esquina de Zulueta y Ánimas, en La Habana. Es un error, El Sloppy habanero se anticipó en 16 años al del lado de allá, que se inauguró en 1934 y tres años después se instalaba en la calle Duval, ubicación que todavía mantiene, mientras que otro bar llamado ‘Capitán Tony’ ocupaba el espacio que el Sloppy original dejaba libre. “Capitán Tony” no tiene la animación del Sloppy ni su hechizo, pero allí se da una situación insólita: muchas de las mujeres que lo visitan se despojan del ajustador y lo cuelgan en las tendederas que cruzan el salón.

Si Padura fijó el bar Dos Hermanos en la literatura, y Hemingway el Floridita en Islas en el golfo, el inglés Graham Greene, aficionado al ron añejo e inventor de cocteles diabólicos, inmortalizó el Sloppy —y también al hotel Sevilla— en su novela Nuestro hombre en La Habana, llevada además al cine.

Un detalle interesante aporta una guía de 1954 publicada en Estados Unidos que facilitaba a turistas norteamericanos su visita a la Isla: Sloppy Joe’s era frecuentado por visitantes estadounidenses, no por los norteamericanos residentes. La colonia norteamericana en La Habana prefería el bar ‘Mis amigos’, en 7ma. y 42, Miramar.

El Floridita tuvo fluctuaciones con relación a sus parroquianos. La mayoría de ellos era de origen norteamericano hasta el inicio de la II Guerra Mundial. Durante la conflagración bélica se llenó de cubanos. Los norteamericanos no podían venir a causa de la guerra y los cubanos no podían salir. Finalizada la guerra, nacionales y visitantes disfrutaron juntos su Daiquirí, que figura en la lista de diez grandes cocteles del mundo.

En 1937, el corresponsal en La Habana de la agencia norteamericana AP dedica una crónica a Constantino Ribalaigua.

Refiere que un grupo de amigos conversaba sobre béisbol en uno de los bares del Hotel Nacional cuando uno de ellos preguntó sobre quién podría considerarse el mejor cantinero cubano. Constantino Ribalaigua respondió el barman que los atendía, aunque la pregunta no le estaba dirigida expresamente. De inmediato, refiere el periodista, uno de los del grupo telefoneó al Sloppy y a Prado 86 y también a los bares de los hoteles Plaza y Sevilla, muy famosos en la época. Obtuvo la misma respuesta. El reportero visitó a Constantino en Floridita y quedó maravillado. Confesó el barman que sus mejores cocteles eran Daiquirí, Presidente y Pepín Rivero, inspirado en el director-propietario del Diario de la Marina.

UNA PREGUNTA NO ACLARADA DEL TODO.

Si es posible precisar el origen de muchos cocteles y mencionar a sus creadores por su nombre, el “Cuba Libre” queda en el misterio. Todavía a fines del siglo XIX no se conocía en Cuba la palabra coctel. La ginebra superaba al ron en el gusto de los bebedores y se hablaba de compuestos, achampanados y meneados.

La intervención militar norteamericana puso una nota de modernidad en los bares cubanos, y ron, refresco de cola y hielo hicieron una mezcla de campeonato. Cesó el coloniaje español, la Isla quedó bajo la égida de Estados Unidos y nació una república mediatizada.

Pero la gente, con una buena dosis de ingenuidad, levantaba su vaso y decía: Cuba Libre. En 1902 surgía el bar La Florida que, con el tiempo, pasó a ser el Floridita, y existían ya entonces el American Club, que quebró y reabrió después y la cantina que daba servicio a las tropas norteamericanas destacadas en el campamento de Columbia. Existía, como ya se dijo, el Dos Hermanos. Se habla, asimismo, de un bar Americano, que hemos podido localizar, si es que existió.

En cualquiera de ellos pudo surgir el “Cuba Libre”. “La Bodeguita del Medio” entusiasmó a los visitantes. Su fundador, Ángel Martínez, repetía que a los 12 años de edad su padre lo condenó a cadena perpetua detrás de un mostrador. En 1942 compró el establecimiento que entonces se llamaba La Complaciente y que no era más que una bodega de barrio. Allí su esposa Armenia comenzó a cocinar para unos pocos clientes, entre ellos Felito Ayón, un animal de la noche habanera que se vincula, como impresor, a hitos imprescindibles de la poesía cubana, como la Elegía a Jesús Menéndez, de Nicolás Guillén con dibujos de Carlos Enríquez.

Felito, que tenía su negocio en la misma cuadra de lo que se llamaba ya La Casa Martínez, decía a sus clientes: «Si no estoy en la imprenta, búscame en la bodega, una bodeguita que está en el medio de la calle». De ahí surgió La Bodeguita del Medio, algo tan obvio que a nadie se le ocurrió antes. Así se llama este establecimiento desde el 26 de abril de 1950.

Martínez terminó desembarazándose de los víveres y licores habituales en las bodegas y puso unas pocas mesas en el reducido espacio de que disponía, creció la fama de la cocina de Armenia, reforzada luego por las manos prodigiosas de «La China» Silvia Torres, y los mojitos, que adquirieron allí carta de ciudadanía internacional, hicieron el resto.

Por allí ha pasado todo el mundo, es un decir. Al igual que por el bar Vista al Golfo del Hotel Nacional, con el coctel que lleva el nombre del establecimiento hotelero en la mano, donde se puede hoy apreciar la extensa galería de fotos de famosos que adornan las paredes; clientes todos de la instalación.

BARS AND DRINKS OF MY OLD HAVANA AND HIS HISTORY. VIDEO & PHOTOS..

BARS AND DRINKS OF MY OLD HAVANA AND HIS HISTORY. VIDEO & PHOTOS..

Let’s take an imaginary tour of the long history of Bars and Drinks in our capital starting with a historic visit to the ‘Floridita’ following the bar “Vista al Golfo” of the National Hotel of Cuba, then passing through the “Sloppy Joe’s”, “Bodeguita del Medio “and” Dos Hermanos “.

Each of these establishments with their Cuba Libre individuals in the Gulf View of the National and Sloppy Hotel, while the Bodeguita del Medio and the Floridita with the Mojito and the Daiquirí, Dos Hermanos offers its so-called “Havana Special”.

It is worth noting the validity of that drink that some call the Cuban Manhattan, a mixture whose invention is attributed to Constantino Ribalaigua, a Catalan barman based in the Cuban capital, who was inspired by a passenger and freight transport line that made the New route York-Key West-Havana-New York.

THE NEW YORK ROUTE-CAYO BONE-HAVANA-NEW YORK.

From that city, the train took two days to reach Key West, where a ferry-boat service, on a ten-hour cruise, transported the wagons to Havana. That route became known as The Havana Special and allowed Cuba to take advantage of it to reaffirm itself as an important supplier of the North American market. Crossing the sea sitting comfortably in a railroad car that previously advanced on the narrow summit of a coral mountain, looks like a fairy thing.

As fairies do not exist, only a man like the billionaire Henry Flagler was capable of a company like that that extended the railroad to Miami and from there, from islet to islet, he took it to Key West to connect with Cuba, the rest of the Caribbean and the Panama Canal. Anyway, on January 22, 1912, with the arrival in Key West of the first train from Miami, Flagler made his dream come true, and that same day he embarked towards Havana in order to promote his route over the keys.

Twenty-three years later, on September 2, 1935, a category five hurricane partially destroyed the railway infrastructure. The owners of The Havana Special sold what was left to the state of Florida. Part of those ruins is still visible. On parts of them, the road network was erected which, since 1938, links the Florida keys to each other and links them with the peninsula. Since then the ferry did not transport railroad cars.

They continued their line of tickets and general cargo and gave travelers on both sides the opportunity to visit the opposite shore with their own car.

The Key West ferry was interrupted after 1959. Today, Havana Special is only the cocktail created by Constantino Ribalaigua, while in the Cayo a bust of Flagler recalls the history of its famous railway.

The Dos Hermanos Bar is located in front of the Havana Special pier and opened in 1892, which makes it one of the oldest bars in the Cuban capital. It was characterized by its long hardwood bar, incomplete since a piece was cut in order to place it in one of the bars of the Moka hotel, in Las Terrazas.

Still, it’s still long. The Spanish poet Federico García Lorca frequented the Dos Hermanos during his Cuban stay in 1930, and there was also, among others, Alejo Carpentier and Enrique Serpa, author of novels such as Contraband and La trap, and an anthological tale, Shark fins.

And, of course, the inevitable Hemingway, which in the festive opinion of some wandered through all the bars and canteens of Havana, although he focused his preference on the Floridita. In Dos Hermanos, “with clumsy steps that led him to small but satisfying freedom,” entered one afternoon Andres, the protagonist of Horse Fever (1988), the initial novel by Leonardo Padura.

Floridita was until 1959 the most famous bar in the city, but Sloppy Joe’s was always the one with the most sales. I assumed that the Sloppy Joe’s of Key West preceded east of the corner of Zulueta and Ánimas, in Havana. It is a mistake, The Sloppy Havana was anticipated in 16 years next door, which opened in 1934 and three years later was installed in Duval Street, a location that still remains, while another bar called ‘Captain Tony’ occupied the space that the original Sloppy left free. “Captain Tony” does not have the animation of Sloppy or his spell, but there is an unusual situation: many of the women who visit him take off the adjuster and hang it on the clotheslines that cross the room.

If Padura set the Dos Hermanos bar in the literature, and Hemingway the Floridita in Islands in the gulf, the Englishman Graham Greene, añejo rum fan and inventor of diabolic cocktails, immortalized the Sloppy – and also the Hotel Sevilla – in his novel Our Man in Havana, also taken to the movies.

An interesting detail is provided by a 1954 guide published in the United States that made it easier for American tourists to visit the Island: Sloppy Joe’s was frequented by American visitors, not American residents. The American colony in Havana preferred the ‘My friends’ bar, in the 7th. and 42, Miramar.

The Floridita had fluctuations in relation to its parishioners. Most of them were of North American origin until the beginning of World War II. During the war conflagration, it was filled with Cubans. The Americans could not come because of the war and the Cubans could not leave. After the war, nationals, and visitors enjoyed their Daiquirí together, which is on the list of ten great cocktails in the world.

In 1937, the correspondent in Havana of the North American agency AP dedicates a chronicle to Constantino Ribalaigua.

He says that a group of friends talked about baseball in one of the bars of the National Hotel when one of them asked about who could be considered the best Cuban bartender. Constantino Ribalaigua answered the bartender who attended them, although the question was not addressed expressly. Immediately, the journalist refers, one of the group called Sloppy and Prado 86 and also the bars of the Plaza and Seville hotels, very famous at the time. He got the same answer. The reporter visited Constantine in Floridita and was amazed. The barman confessed that his best cocktails were Daiquirí, President and Pepín Rivero, inspired by the director-owner of the Diario de la Marina.

A QUESTION NOT CLEARED FROM EVERYTHING.

If it is possible to specify the origin of many cocktails and mention their creators by name, the “Cuba Libre” remains in the mystery. At the end of the 19th century, the word cocktail was not known in Cuba. Gin outperformed rum in the taste of drinkers and there was talk of compounds, chamfering and wiggling.

The US military intervention put a note of modernity in Cuban bars, and rum, cola, and ice made a mix of the championship. The Spanish colony ceased, the Island was under the aegis of the United States and a mediated republic was born.

But people, with a good dose of naivety, raised their glass and said: Cuba Libre. In 1902, the bar La Florida emerged, which, over time, became the Floridita, and there was already the American Club, which broke and then reopened and the canteen that served the outstanding North American troops in the Columbia camp. There was, as already said, the Two Brothers. There is also talk of an American bar, which we have been able to locate if it existed.

In any of them, the “Cuba Libre” could emerge. “La Bodeguita del Medio” excited visitors. Its founder, Ángel Martínez, repeated that at 12 years of age his father sentenced him to life imprisonment behind a counter. In 1942 he bought the establishment that was then called La Complaciente and that was nothing more than a neighborhood winery. There, his wife, Armenia, began cooking for a few clients, among them Felito Ayón, an animal of the Havana night who is linked, as a printer, to essential landmarks of Cuban poetry, such as Elegía a Jesús Menéndez, by Nicolás Guillén with drawings by Carlos Enriquez.

Felito, who had his business in the same block as what was already called La Casa Martínez, said to his clients: «If I’m not in the printing press, look for me in the cellar, a wine cellar that is in the middle of the street». From there emerged La Bodeguita del Medio, something so obvious that nobody came up with it before. This is the name of this establishment since April 26, 1950.

Martinez ended up getting rid of the usual groceries and liquors in the cellars and put a few tables in the small space he had, the fame of Armenian cuisine grew, then reinforced by the prodigious hands of “La China” Silvia Torres, and the Mojitos, who acquired there a letter of international citizenship, did the rest.

Everyone has passed through it, it is a saying. As with the Vista al Golfo bar of the National Hotel, with the cocktail that bears the name of the hotel establishment in your hand, where you can now appreciate the extensive gallery of photos of celebrities adorning the walls; customers all of the installation.

Agencies/ Lecturas/ Ciro Bianchi/ Extractos/ Excerpts/ Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ www.TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.