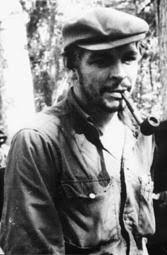

A LA CAZA POR EL “CHÉ” GUEVARA “VIVO O MUERTO”. FOTOS

Desde principios del año 1965, la CIA comenzó a escuchar rumores sobre el plan del Che para exportar la Revolución de Castro a otros lugares, lo que para ellos consideraba que el deber de Cuba era alentar a otros “movimientos de liberación nacional” en todo el mundo. Los funcionarios de la CIA inmediatamente pusieron a Gustavo Villoldo y otros Cubano-americanos en el rastro.

QUIEN FUE EL AGENTE QUE CAZÓ AL “CHÉ”

Gustavo Villoldo es el agente de la CIA que partió a la caceria del “Che”, quien lo persiguió desde el Caribe hasta África y América Latina para vengar la muerte de su padre, ejecutado por el “Che” en Cuba, y luchar contra el estilo de comunismo de los Castro.

Villoldo cruzó un río en plena noche para infiltrarse en el lado izquierdista de una sangrienta guerra civil en la República Dominicana para ver los rumores de que el Che estaba allí. El argentino no se encontraba por ningún lado. Dirigió a un grupo de agentes cubanoamericanos de la CIA al Congo a finales de ese año, simplemente extrañó al Che cuando escapó a la vecina Tanzania con otros 120 cubanos después de que el gobierno aplastó a las fuerzas rebeldes.

“Lo identificamos allí y estuvimos allí durante 28 días, pero todo estaba perdido para el Che y escapó”, dijo Villoldo. “Unos días más y podríamos haberlo cercado”. Villoldo recordó que sus órdenes de la CIA eran localizar al Che, “pero mi intención era atraparlo, vivo o muerto”.

El Che se escondió durante meses después del Congo, lamiendo las heridas de su psiquis de combate y buscando otro país donde pudiera probar suerte en la subversión. Después de discutir con los Castro, se estableció en Bolivia.

El Che duró apenas 12 meses en las selvas de Bolivia, los primeros ocho escondidos mientras preparaba su campaña guerrillera, los últimos cuatro huyendo de un batallón de guardabosques del ejército boliviano, entrenados por boinas verdes del ejército de EE. UU. Y asesorados por un equipo de tres exiliados cubanos trabajando para la CIA. Un funcionario de la CIA que dirigió la misión de Bolivia confirmó que Villoldo era el “agente principal en el campo”.

Dos de los tres hombres de la CIA, el operador de radio Félix Rodríguez y el asesor de la policía urbana Julio García, aparecieron más tarde en libros que daban sus propias historias, a veces adornadas, sobre la búsqueda del Che.

Pero el líder del equipo, Villoldo, ha mantenido su versión de los eventos para sí mismo, hasta ahora.

Villoldo llevaba credenciales del ejército boliviano que lo identificaban como el Capitán Eduardo González. Llevaba uniforme de ejército boliviano y era tan discreto que varios oficiales bolivianos que trabajaron con él durante varias semanas nunca se dieron cuenta de que era un hombre de la CIA.

Entre sus tareas: evaluar información del interrogatorio del socialista francés Regis Debray, quien había escrito un libro brillante sobre la ideología de la guerrilla de Castro. Debray había sido capturado después de visitar al Che en las selvas bolivianas. En una desagradable disputa que continúa hasta el día de hoy, la familia del Che ha acusado a Debray de traicionarlo. Debray lo niega. Villoldo dijo, usando la jerga cubana para alguien que confiesa todo: “Habló hasta por los codos”.

Che, de 39 años, fue herido y capturado durante un tiroteo en la jungla el 8 de octubre de 1967. Fue ejecutado por dos soldados bolivianos al día siguiente en la escuela de adobe en la aldea de La Higuera, por orden del dictador militar boliviano, René Barrientos

“En ningún momento, ni yo ni la CIA tuvimos voz en la ejecución del Che”, dijo Villoldo. “Esa fue una decisión boliviana”.

El cadáver del Che fue atado a los patines de un helicóptero del ejército el 9 de octubre y voló a la ciudad agrícola cercana de Vallegrande, donde los Rangers que seguían al Che habían establecido una base cerca de una pista de aterrizaje. El cuerpo fue exhibido para campesinos y periodistas durante las siguientes 24 horas, en una camilla colocada sobre un lavabo de cemento en la lavandería del Hospital Nuestro Señor de Malta, realmente un cobertizo pegado a la parte posterior del hospital. Y luego desapareció por 30 años.

Gary Prado, el capitán que comandaba la compañía Ranger que capturó al Che, y que luego ascendió al rango de general, insistió durante años en que el cuerpo había sido incinerado y las cenizas dispersadas. Otros susurraron que fue arrojado desde un helicóptero a la selva más profunda o alimentado a perros salvajes.

Pero luego, a fines de 1995, el general boliviano retirado Mario Vargas le dijo al autor estadounidense John Lee Anderson, quien estaba escribiendo una biografía del Che, que el cuerpo había sido enterrado cerca de la pista de aterrizaje de Vallegrande. Vargas más tarde admitió que había basado su historia en rumores, lo que, irónicamente, fue correcto.

De repente, el pequeño pueblo de 8,000 personas estaba inundado de antropólogos y geólogos forenses cubanos. Lograron localizar cinco restos, solo una fracción de las 32 guerrillas, incluidos izquierdistas bolivianos y peruanos y veteranos cubanos de la Sierra Maestra, asesinados en el área en 1967 y enterrados en tumbas sin marcar.

Pero durante los siguientes 16 meses, no hubo signos del cuerpo del Che. Y el Che, a pesar de que todos los cubanos hablaron de la importancia de dar los funerales adecuados a todos los guerrilleros muertos, fue el verdadero premio.

GUSTAVO VILLOLDO PROPONE A ALEIDA GUEVARA INFORMARLE DONDE ESTABAN LOS RESTOS

Y luego, esa primavera, Gustavo Villoldo salió a la superficie e hizo una oferta explosiva.

En un mensaje del 23 de abril entregado clandestinamente a la hija del Che, Aleida, por una partidaria de Castro que vive en La Habana, Villoldo se ofreció a desenterrar personalmente los restos del Che y entregarlos a ella por razones humanitarias.

Villoldo escribió que solo dos años antes, había creído que el cuerpo del Che debería permanecer oculto. Pero varios factores, agregó, lo llevaron a “una profunda reconsideración”.

“No he renunciado a los principios personales, ideológicos y políticos que me llevaron a luchar contra Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara”, escribió a Aleida. “Pero de la misma manera, Estados Unidos quiere recuperar a sus muertos en Corea y Vietnam, la viuda y los niños de Guevara tienen derecho a exigir su cuerpo”.

Sin política ni propaganda, porque no quería exponerse a los ataques de exiliados en Miami que podrían resentir su decisión de cooperar. “Soy un exiliado político y vivo en una sociedad de exiliados muy difícil, cargada de múltiples presiones”.

Y quería el control exclusivo sobre todos los ingresos publicitarios. Dijo que cualquier ganancia derivada de la fanfarria que seguramente estallará, debe ser donada a becas para estudiantes de medicina bolivianos.

Villoldo ahora reconoce que tenía otra preocupación en mente: dado que era probable que los huesos del Che finalmente se recuperaran, después de todo, los cubanos estaban cavando en el área correcta, inyectarse en las excavaciones le quitaría ventaja al probable triunfo de Castro. “Todavía había política y propaganda involucradas, y todavía no quería que Castro capitalizara completamente esto”, dijo.

Los funcionarios cubanos luego acusarían de que Villoldo solo estaba tratando de desviar la búsqueda, y atacarían su demanda de controlar toda la publicidad como un esfuerzo grosero para capturar el centro de atención y sacar provecho de los huesos del Che.

Pero la oferta de Villoldo, de hecho, desató una carrera por los restos entre los cubanos, Villoldo e incluso los bolivianos que querían mantener la tumba del Che en Vallegrande como atracción turística y monumento político.

“Me dijeron que Fidel Castro lanzó un verbal ataque porque no podía permitir que el gusano [gusano del exilio] que aconsejó al ejército boliviano en la búsqueda del Che, y al hombre que sabía que había enterrado al Che, fuera el hombre que lo devolvió a Cuba”.

Mientras tanto, los funcionarios municipales de Vallegrande declararon que los restos del Che son un “patrimonio nacional” y aplazaron una moratoria en la excavación hasta mediados de junio. Luego, la ciudad comenzó a promover un recorrido a pie por la “Ruta del Che” a $70 por día y a planificar un museo.

Loyola Guzmán, quien de joven era tesorera de la facción marxista boliviana que siguió al Che a las selvas, argumentó que si el Che daba su vida por Bolivia, sus restos pertenecían correctamente al suelo boliviano. “Su vida fue un ejemplo de heroico internacionalismo que ningún país debería monopolizar”, dijo Guzmán, ahora un defensora de los derechos humanos.

Mientras tanto, Villoldo había contratado a una empresa del sur de Florida cuyo radar de búsqueda por tierra podría localizar el lugar de enterramiento del Che en caso de que la memoria de Villoldo le fallara, contactó a un agente de reservas y negoció con un equipo de televisión de tres hombres en Miami para grabar su búsqueda.

Niega haber querido publicidad para sí mismo.”Quería que la historia supiera exactamente cómo sucedieron las cosas”, dijo.

Villoldo había hecho reservas el 26 de junio desde Miami a Bolivia, y después de mucho cabildeo, obtuvo permiso para buscar del ministro boliviano de Recursos Humanos, Franklin Anaya, ex embajador en La Habana y autor de un libro comprensivo sobre Cuba que actuaba como enlace boliviano. con los antropólogos cubanos.”Tenía mis maletas empacadas”, dijo Villoldo.

ARREGLO EN LA BUSQUEDA DE LOS RESTOS

Más tarde, los medios de comunicación alegaron que Anaya y el presidente boliviano Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada habían hecho un trato con Castro para favorecer al equipo cubano. Las cuentas no pudieron confirmarse, pero Anaya canceló repentinamente las reservas de avión de Villoldo. Villoldo apeló al presidente Sánchez de Lozada y nuevamente fue autorizado para volar a Bolivia. Pero amigos bolivianos le aconsejaron que se quedara en Miami, dijo Villoldo.

“Mis amigos me dijeron que Castro sabía de mi llegada prevista y que había alguna posibilidad de que los cubanos tomaran medidas contra mí”, dijo Villoldo. “Basado en la advertencia. . . Decidí esperar y ver qué pasó”.

Lo que sucedió fue una carrera cubana para encontrar el cuerpo.

Apenas 18 días después de que la carta de Villoldo llegara a Aleida Guevara, y un día después de que terminara la prohibición municipal de excavar, los cubanos iniciaron una búsqueda de los restos del Che con una intensidad nunca antes vista en los últimos 16 meses de excavación. Trabajaron desde el amanecer hasta la puesta del sol, prácticamente sin parar. Tenían tanta prisa que utilizaron una herramienta de excavación considerada anatema por todos los expertos en su campo: una excavadora.

Para el 27 de junio, un equipo cubano dirigido por Jorge González, jefe del Instituto de Medicina Legal de La Habana, había cavado varias trincheras y pozos de prueba en el área descrita por el general Vargas, pero apareció con las manos vacías. El tiempo se acababa.

El gobierno del presidente Sánchez de Lozada ordenó que se detuvieran todas las excavaciones el 28 de junio, aparentemente debido a la elección el 2 de junio de un nuevo presidente boliviano, Hugo Banzer. Ex dictador militar en la década de 1970, se sabe que Banzer tiene poca simpatia por el Che, Castro o Cuba. Sánchez de Lozada podría haber presumido correctamente que sus acciones podrían ser examinadas sin simpatía por su sucesor.

De hecho, Banzer, que asumió el cargo en agosto, prometió investigar el papel de su predecesor para ayudar a Cuba a desenterrar los restos del Che e investigar informes de prensa de que Anaya podría beneficiarse personalmente de los derechos de publicidad de la historia de la excavación.

BUSQUEDA RAPIDA POR ENCONTRAR LOS RESTOS

Los excavadores cubanos se reunieron hasta las 4 en punto de la mañana del 28 de junio para decidir dónde enfocar su último día de excavación, recordó Alejandro Inchaurregui, uno de un equipo de antropólogos forenses argentinos llamados para ayudar a los cubanos.

Los estudios de radar de tierra realizados por el equipo de búsqueda cubano-argentino a principios de 1997 revelaron una docena de puntos de tierra perturbada que pod rían ser tumbas secretas, o tal vez rocas desplazadas o árboles caídos. De estos, tres, en particular, tenían todas las características de ser hechos por el hombre. Aquí es donde se pusieron a trabajar. Con una excavadora.

rían ser tumbas secretas, o tal vez rocas desplazadas o árboles caídos. De estos, tres, en particular, tenían todas las características de ser hechos por el hombre. Aquí es donde se pusieron a trabajar. Con una excavadora.

En el primer lugar, configuraron la cuchilla de la excavadora para raspar cuatro pulgadas de tierra con cada pasada. Casi dos horas después, golpearon una roca y no hay señales de ningún hueso. Pasaron al puesto número 2. Dieciocho raspados de la excavadora más tarde, casi exactamente seis pies abajo, la cuchilla descubierta y rompió partes de un esqueleto humano.

Lo que los cubanos habían encontrado eran siete cuerpos, en dos grupos de tres y cuatro, separados por 2 1/2 pies, enterrados en un pozo encajado entre la vieja pista de tierra de Vallegrande al norte y el cementerio cercano al sur.

El jubilo estalló cuando se descubrió el segundo cuerpo, el medio en el grupo de tres, y se descubrió que no tenía manos. Las manos del Che fueron amputadas después de su muerte como prueba de su fallecimiento.

Pero los restos del Che aún tenían que ser identificados oficialmente por funcionarios del gobierno boliviano para que pudieran ser liberados y trasladados a Cuba. “La gente del Ministerio del Interior nos decía que nos moviéramos rápido. A medida que se acercaba la inauguración de Banzer, los tornillos se apretaron”, dijo Inchaurregui.

Y así, en la oscuridad de la noche del 5 de julio, un convoy de 10 vehículos hizo una carrera de cinco horas y 150 millas a velocidades vertiginosas a lo largo de las peligrosas carreteras de montaña para transferir los restos a la capital provincial de Santa Cruz.

Allí, los restos sin manos fueron identificados rápidamente. Los dientes excavados coincidían perfectamente con un molde de yeso de los dientes del Che fabricado en La Habana antes de partir hacia el Congo para poder identificarlo si moría en combate.

Y hubo un factor decisivo, revelado a ‘Tropic’ por Jaime Nino de Guzmán, que había sido un comandante del ejército boliviano y piloto de helicóptero en 1967, y que había visto al Che vivo como un cautivo en La Higuera mientras transportaba agentes y suministros dentro y fuera.

El Che lucia terrible, recordó Nino de Guzmán el mes pasado desde su casa en La Paz. Le habian disparado en la pantorrilla derecha, su cabello estaba cubierto de tierra, estaba desmenuzado y sus pies estaban cubiertos de vainas de fundas de cuero. Pero el Che mantuvo la cabeza alta, miró a todos a los ojos y solo pidió algo para fumar. Raramente se le habia visto sin un cigarro cubano en la mano después de que Castro triunfó, el Che había cambiado a una pipa para la guerra de guerrillas.

“Me dió lástima, se veía tan terrible y le di mi pequeña bolsa de tabaco importado para su pipa. Él sonrió y me dio las gracias”, recordó el piloto en una entrevista telefónica.

Treinta años después, dijo Inchaurregui, estaba inspeccionando una chaqueta azul desenterrada junto a los restos sin manos cuando encontró un pequeño bolsillo interior, casi oculto y aparentemente extrañado por los soldados que registraron el cuerpo del Che. Escondido dentro había una pequeña bolsa de tabaco para pipa.

“Debo decirte que tenía serias dudas al principio. Pensé que los cubanos encontrarían huesos viejos y lo llamarían Che”, dijo Nino de Guzmán. “Pero después de escuchar sobre la bolsa de tabaco, no tengo dudas”.

EUFORIA ANTE LA IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LOS RESTOS DEL “CHÉ” GUEVARA

“Solo viendo la emoción genuina, la euforia genuina en la cara de los cubanos allí me asegura que se trata de los restos del Che”, dijo John Lee Anderson, el autor estadounidense. Anderson fue testigo de las etapas finales de la excavación. “Simplemente estaban abrumados, llorando y abrazándose”.

Recuperar los restos del Che fue un triunfo de propaganda para Castro, cuya ideología casi se ha derrumbado desde el colapso del bloque soviético.

El Che era, literalmente, el chico del cartel de la Revolución Cubana. Era un médico asmático nacido en Argentina que se unió a Castro en la guerra contra la dictadura de Batista, luego rechazó la ortodoxia soviética y dio su vida tratando de exportar una ideología que consideraba más humanitaria que comunista. Un perfil de acero de cinco pisos y 17 toneladas del Che cubre la fachada de la sede del Ministerio del Interior en la Plaza de la Revolución de La Habana. Es un telón de fondo frecuente de los discursos más importantes de Fidel, un logotipo virtual de la capital cubana.

Hasta el día de hoy, el Che sigue siendo un ícono mundial para el cambio radical, sus muchos errores políticos y económicos y sus derrotas guerrilleras en su mayoría olvidadas y en gran medida eclipsadas por su enorme impacto cultural. Su imagen romántica, amplificada por su muerte prematura y su comunismo poco ortodoxo, permitió que su atractivo trascendiera las líneas ideológicas.

.. El Che se ha convertido en un símbolo universal y multigeneracional de los años 60, como los Beatles, un hombre lo suficientemente político como para capturar la política de la época en un sentido amplio sin quedar empantanado en todo el tema de la Guerra Fría ”, dijo Jorge Castaneda, un autor mexicano de una de las tres biografías del Che publicadas ese año. Pero la historia del Che también se trata de dinero. Cuba compró 10.000 relojes Swatch de fabricación suiza con el rostro y barba del Che y los vendió en boutiques de La Habana. El entonces ex ministro de Cultura, Armando Hart, escribió un CD-ROM multimedia en el Che, con un precio de $60.

El historiador de la música de La Habana, Santiago Feliu, ha reunido una antología de 135 canciones sobre el Che, que saldria a la venta entonces. Felu dijo que las canciones incluirán ritmos tradicionales cubanos, así como rock y blues, y algunas de cuyas letras son “críticas por aquellos que han usado mal y vulgarizado la imagen del Che”. Quizás se refiere a los vendedores ambulantes cubanos que ofrecen a los turistas la imagen del Che en todo, desde tallas de madera hasta cuero martillado e incluso hojas secas de uva marina inscritas con algunos de sus famosos dichos.

Es dudoso que se refiera a los llaveros, carteles y camisetas con la imagen del Che que siempre se venden en las tiendas del gobierno cubano a $6 a $10 por postal.

Cuba trazó la línea de comercialización de la imagen del Che el año pasado, persiguiendo a un cervecero británico que fabricó brevemente una cerveza “Che” con su imagen y el eslogan cautivador, “Prohibido en los EE.UU. Debe ser bueno”.

Por supuesto, ciertos artefactos del Che, los auténticos, como viejos rifles oxidados, mochilas y fotografías amarillentas encontradas en Bolivia y llevadas silenciosamente a Cuba por agentes cubanos durante años, no pueden ser producidos en masa. Pero aún pueden ser explotados.

Eso se aplica especialmente al último artefacto del Che: sus huesos perdidos hace mucho tiempo.

Incluso Gustavo Villoldo, que cazó a Guevara en todo el mundo, ahora reconoce que estos son probablemente los restos del Che. “Aunque inicialmente lo dudaba, toda la evidencia apunta a eso”, dijo después de revisar la evidencia.

Aún queda otro misterio, ya que la tumba donde los cubanos encontraron siete restos no coincide con detalles insignificantes de la tumba donde Villoldo dice que enterró al Che y a otras dos guerrillas.

“No puedo explicar eso en absoluto”, dijo. “Ese fue el momento más importante de mi vida, y puedo recordar los detalles como si estuvieran sucediendo en este momento, aquí mismo. Y simplemente no coinciden”.

PLANES PARA DESHACERSE DE LOS RESTOS DEL “CHE”

Villoldo se enteró de la captura del Che mientras estaba en el puesto de mando avanzado del Ranger en una ciudad cercana. Villoldo se apresuró a Vallegrande, llegando el 9 de octubre, solo dos horas antes de que el helicóptero con el cuerpo del Che aterrizara en una pista de aterrizaje de tierra abarrotada de cientos de periodistas y gente curiosa de la ciudad.

“Nunca lo vi con vida, pero no tenía interés en eso o en hablar con él”, dijo. “Nunca fue personal para mí, a pesar de que el hecho de que el Che había contribuido a la muerte de mi padre siempre estuvo en la parte de atrás. de mi mente. Era solo un trabajo”.

Al día siguiente, 10 de octubre, los principales comandantes militares bolivianos y Villoldo se reunieron en el restaurante del único hotel de Vallegrande, el Hotel Teresita de dos pisos, para discutir cómo deshacerse del cuerpo del Che, recordó.

Al igual que en la exhumación del Che 30 años después, fue una carrera contra reloj: los oficiales del ejército habían recibido la noticia de que algunos de los familiares del Che se dirigían a Vallegrande para reclamar el cuerpo.

Pero tanto los bolivianos como Villoldo querían “desaparecerlo”. “Pensamos que era importante disponer de él con la máxima seguridad para negarle a Castro los huesos y la posibilidad de construir algún tipo de monumento que pudiera explotar tanto ideológica como comercialmente”, recordó Villoldo.

Alguien sugirió incinerarlo, dijo Villoldo, pero argumentó que, en ausencia de un verdadero crematorio en Vallegrande, “todo lo que estaríamos haciendo sería celebrar una barbacoa. Les dije que habían escrito una bonita página en la historia del ejército boliviano y que no deberían terminar así”.

Los comandantes del ejército finalmente decidieron amputar las manos para su futura identificación y luego enterrar el cuerpo en secreto. El Jefe del Ejército, general Alfredo Ovando, asignó a Villoldo para llevar a cabo las decisiones. Villoldo fue fotografiado por periodistas bolivianos que miraban por encima de los hombros de los dos médicos que realizaron una rápida autopsia del cadáver y luego, después de que los periodistas se fueron, le amputaron las manos.

Fue entonces cuando Villoldo cortó un mechón del cabello desaliñado del Che, al menos inicialmente para una boina verde de los Estados Unidos que le había pedido un recuerdo. Pero, reconoció con tristeza, mantuvo algunos hilos. “Ni siquiera recuerdo si lo corté con un cuchillo o unas tijeras. No estaba interesado y no tenía intención de mantenerlo. No soy ese tipo de persona. Pero con el tiempo, pensé, bueno. . . “. Todavía lo tiene, aunque nunca lo ha mostrado en público.

Villoldo dijo que se le proporcionó un guardia de seguridad, un conductor para un camión para transportar el cuerpo y un segundo conductor para la excavadora que lo enterraría.

INTERROGANTES: UN ENIGMA FINAL

Tomó una siesta, se despertó a la 1:45 a.m. y fue a la lavandería del hospital. El cuerpo del Che estaba tendido sobre un lavabo. En el suelo de tierra, a un par de metros de distancia, estaban los cuerpos en descomposición rápida de otros dos rebeldes.

Es la misma escena descrita por el piloto de helicóptero Nino de Guzmán y por Alberto Suazo, quien en 1967, cuando era un joven reportero de United Press International, vio el cadáver del Che en el hospital. Pero Suazo recordó haber visto “otros tres o cuatro cadáveres de guerrillas” en algún lugar del patio detrás del hospital, lo que es consistente con el relato de Guzmán de volar en siete cadáveres.

Villoldo insiste en que solo vio el Che y otros dos cuerpos.

Ordenó a sus ayudantes que cargaran los tres cadáveres en el camión. Condujeron a la pista de aterrizaje en la oscuridad total hasta que vio un lugar probable cerca del cementerio amurallado de Vallegrande, recordó Villoldo. Le dijo al conductor que se detuviera.

El lugar estaba al sur de la pista de aterrizaje y al oeste del cementerio, en un área donde una excavadora ya había estado trabajando cerca para que no fuera aparente una tumba nueva, dice Villoldo.

Pero la fosa común excavada por los cubanos estaba al norte del cementerio.

Villoldo dice que mientras envió a uno de sus hombres a buscar la excavadora, tomó lecturas de la brújula y recorrió distancias desde cuatro puntos que le permitirían encontrar el lugar exacto nuevamente. Él no escribió nada, dice, pero memorizó las mediciones.

Luego retrocedieron el camión hasta el borde de un hoyo natural en el suelo y descargaron los tres cadáveres. Villoldo ordenó al conductor de la excavadora que los cubriera. Tanto Villoldo como el conductor de la excavadora, que aún vive en Vallegrande y fue entrevistado por Inchaurregui, recuerdan que comenzó a llover hacia el final del entierro.

El conductor de la excavadora dijo que no recordaba exactamente cuántos cuerpos enterró o si el sitio estaba al norte o al oeste del cementerio. Ni siquiera puede decir con certeza que el Che estaba entre los cuerpos, le dijo Inchaurregui a Tropic.

Inchaurregui dijo que cree que Villoldo miente o se equivoca al enterrar solo tres cuerpos. “Obviamente tiene consideraciones políticas para decir lo que dice. No me sorprende que después de 30 años todavía esté tratando de desviar a todos”, dijo el argentino.

El supervisor de la CIA de Villoldo para la misión de Bolivia, ahora retirado en el norte de Florida pero que todavía habla solo bajo condición de anonimato, dijo esto: “Gus no exagera. Le creería si dice que enterró a tres”.

Entonces, ¿qué tal esos siete restos? Quienes fueron ‘Willy’ Simon Cuba Sarabia quien ayudó al Che cuando fue herido en la Quebrada de Yuro. Otros fueron Orlando Tamayo “Antonio”; Aniceto Reynago Gordillo “Aniceto”; René Martínez Tamayo; Alberto Fernández Moisés de Oca “Pacho” y Juan Pablo Chang Navarro.

¿Podrían los conductores de camiones o excavadoras haber enterrado a las otras cuatro guerrillas más temprano en el día y luego haber llevado a un Villoldo inconsciente al mismo lugar para enterrar al Che y a los otros dos?

“De ninguna manera. Les dije a dónde ir, dónde parar. Elegí el lugar solo”, dijo Villoldo.

¿Podrían los conductores haber enterrado los otros cuatro cuerpos en el mismo lugar que el Che y los otros dos al día siguiente, tal vez regresando a donde habían dejado la excavadora después de las lluvias?

No es probable, dijo Inchaurregui. El patrón de las marcas de excavación en el pozo desde el que se excavaron los siete cuerpos indicaba que una excavadora lo había cavado con pases de ida y vuelta, no simplemente movía la suciedad sobre los cuerpos de forma natural como describió Villoldo.

El análisis de la dureza de la suciedad también mostró que la tumba tenía un piso común de tierra compacta debajo de todos los cuerpos, y que los siete cuerpos habían sido cubiertos con la misma suciedad al mismo tiempo, agregó Inchaurregui.

“Me parece una apertura y un cierre de la tumba. Son siete cuerpos, no tres. Esa es la evidencia empírica”, concluyó el antropólogo.

¿Podría Villoldo, por una coincidencia trillón a uno, haber enterrado los tres cuerpos en la misma naturaleza donde algún oficial del ejército boliviano había arrojado anteriormente cuatro cadáveres sin enterrar?

“Miré eso y no vi nada”, dijo Villoldo. “Enterré y cubrí tres cuerpos. Lo sé con seguridad. Nunca vi siete cuerpos, ni siquiera supe de siete cuerpos hasta mucho después”.

Hoy, un equipo reducido de cubanos que trabajan a un ritmo más lento permanece en Vallegrande, en busca de unos 23 cadáveres guerrilleros más que se cree enterrados en tumbas sin marcar en la región.

Todavía falta el cuerpo de la segunda guerrilla más notoria: Tamara Bunker, una bella y joven argentina de ascendencia alemana llamada Tanya, una reputada agente de la KGB.

Villoldo sigue decidido a volar a Bolivia para visitar el sitio donde desenterraron los restos sin manos y compararlo con los rumbos y las distancias que registró la noche en que enterró al Che.

Mientras tanto, Villoldo cuida su granja, estudia los mapas a gran escala de Vallegrande, vuelve a leer sus libros sobre el Che e intenta descubrir cómo es posible enterrar tres cuerpos y desenterrar siete.

“Tal vez puedas encabezar esta historia Che: El fin del mito”, sugirió.

HUNTING FOR THE “CHÉ” GUEVARA “ALIVE OR DEAD”. PHOTOS

From the beginning of 1965, the CIA began to hear rumors about Che’s plan to export the Castro Revolution to other places, which for them considered that the duty of Cuba was to encourage other “national liberation movements” throughout the country. world. CIA officials immediately put Gustavo Villoldo and other Cuban-Americans on the trail.

WHO WAS THE AGENT WHO HUNTED “CHÉ”

Gustavo Villoldo is the CIA agent who went on the hunt for “Che”, who pursued him from the Caribbean to Africa and Latin America to avenge the death of his father, executed by “Che” in Cuba, and fight against him. Castro’s style of communism.

Villoldo crossed a river in the middle of the night to infiltrate the leftist side of a bloody civil war in the Dominican Republic to see rumors that Che was there. The Argentine was nowhere to be found. He led a group of Cuban-American CIA agents to the Congo at the end of that year, simply missing Che when he escaped to neighboring Tanzania with 120 other Cubans after the government crushed the rebel forces.

“We identified him there and we were there for 28 days, but all was lost for Che and he escaped,” Villoldo said. “A few more days and we could have fenced him off.” Villoldo recalled that his CIA orders were to locate Che, “but my intention was to catch him, dead or alive.”

Che hid for months after the Congo, licking the wounds of his combat psyche and looking for another country where he could try his luck in subversion. After arguing with the Castros, he settled in Bolivia.

Che lasted just 12 months in the jungles of Bolivia, the first eight in hiding while he prepared his guerrilla campaign, the last four fleeing from a battalion of Bolivian army rangers, trained by green berets from the US Army and advised by a team of three Cuban exiles working for the CIA. A CIA official who led the Bolivian mission confirmed that Villoldo was the “main agent in the field.”

Two of the three CIA men, radio operator Félix Rodríguez and urban police adviser Julio García, later appeared in books that gave their own stories, sometimes ornate, about the search for Che.

But team leader Villoldo has kept his version of events to himself, until now.

Villoldo carried credentials from the Bolivian army that identified him as Captain Eduardo González. He wore a Bolivian Army uniform and was so discreet that several Bolivian officers who worked with him for several weeks never realized that he was a CIA man.

Among his tasks: to evaluate information from the interrogation of the French socialist Regis Debray, who had written a brilliant book on the ideology of Castro’s guerrilla. Debray had been captured after visiting Che in the Bolivian jungles. In a nasty dispute that continues to this day, Che’s family has accused Debray of betraying him. Debray denies it. Villoldo said, using Cuban slang for someone who confesses everything: “He spoke up a storm.”

Che, 39, was wounded and captured during a shooting in the jungle on October 8, 1967. He was executed by two Bolivian soldiers the next day at the adobe school in the village of La Higuera, on the orders of the Bolivian military dictator. , René Barrientos

“At no time, neither I nor the CIA had a voice in Che’s execution,” Villoldo said. “That was a Bolivian decision.”

Che’s corpse was tied to the skids of an army helicopter on October 9 and flew to the nearby agricultural town of Vallegrande, where the Rangers following Che had established a base near an airstrip. The body was displayed for peasants and journalists for the next 24 hours, on a stretcher placed over a cement sink in the laundry room of Hospital Nuestro Señor de Malta, actually a shed attached to the back of the hospital. And then it disappeared for 30 years.

Gary Prado, the captain who commanded the Ranger company that captured Che, and later rose to the rank of general, insisted for years that the body had been cremated and the ashes scattered. Others whispered that he was thrown from a helicopter into the deepest jungle or fed to wild dogs.

But then, in late 1995, retired Bolivian General Mario Vargas told American author John Lee Anderson, who was writing a biography of Che, that the body had been buried near the Vallegrande airstrip. Vargas later admitted that he had based his story on hearsay, which, ironically, was correct.

Suddenly, the small town of 8,000 people was awash with Cuban forensic anthropologists and geologists. They managed to locate five remains, just a fraction of the 32 guerrillas, including Bolivian and Peruvian leftists and Cuban veterans from the Sierra Maestra, murdered in the area in 1967 and buried in unmarked graves.

But for the next 16 months, there were no signs of Che’s body. And Che, despite the fact that all Cubans spoke of the importance of giving adequate funerals to all dead guerrillas, was the real prize.

GUSTAVO VILLOLDO PROPOSES TO ALEIDA GUEVARA TO INFORM HIM WHERE THE REMAINS WERE

And then during that spring, Gustavo Villoldo surfaced and made an explosive offer.

In an April 23 message secretly delivered to Che’s daughter Aleida by a Castro supporter living in Havana, Villoldo offered to personally unearth Che’s remains and hand them over to her for humanitarian reasons.

Villoldo wrote that only two years earlier, he had believed that Che’s body should remain hidden. But several factors, he added, led him to “a deep reconsideration.”

“I have not renounced the personal, ideological, and political principles that led me to fight Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara,” he wrote Aleida. “But in the same way, the United States wants to recover its dead in Korea and Vietnam, Guevara’s widow and children have the right to demand his body.”

Without politics or propaganda, because he did not want to expose himself to the attacks of exiles in Miami who might resent his decision to cooperate. “I am a political exile and I live in a very difficult exile society, fraught with multiple pressures.”

And he wanted exclusive control of overall advertising revenue. He said that any profit derived from the fanfare that is sure to erupt should be donated to scholarships for Bolivian medical students.

Villoldo now acknowledges that he had another concern in mind: Since Che’s bones were likely to eventually be recovered, after all, the Cubans were digging in the right area, injecting himself into the excavations would take away from Castro’s likely triumph. “There was still politics and propaganda involved, and I still didn’t want Castro to fully capitalize on this,” he said.

Cuban officials would then charge that Villoldo was only trying to divert the search, and attack his demand to control all publicity as a rude effort to capture the spotlight and cash in on Che’s bones.

But Villoldo’s offer, in fact, sparked a race for the remains among Cubans, Villoldo, and even Bolivians who wanted to keep Che’s tomb in Vallegrande as a tourist attraction and political monument.

“They told me that Fidel Castro launched a verbal attack because he could not allow the worm [worm from exile] who advised the Bolivian army in the search for Che, and the man who he knew had buried Che, to be the man who returned him. To Cuba”.

Meanwhile, Vallegrande municipal officials declared Che’s remains a “national heritage” and postponed a moratorium on excavation until mid-June. Then the city began promoting a walking tour of the “Che Route” at $ 70 per day and planning a museum.

Loyola Guzmán, who as a young man was treasurer of the Bolivian Marxist faction that followed Che into the jungles, argued that if Che gave his life for Bolivia, his remains correctly belonged to Bolivian soil. “His life of hers was an example of heroic internationalism that no country should monopolize,” said Guzmán, now a human rights defender.

Meanwhile, Villoldo had hired a South Florida company whose ground search radar could locate Che’s burial site should Villoldo’s memory fail him, contacted a reservations agent, and negotiated with a team of television of three men in Miami to record their search.

He denies wanting publicity for himself. “He wanted the story to know exactly how things happened,” he said.

Villoldo had made reservations on June 26 from Miami to Bolivia, and after much lobbying, he obtained permission to seek from the Bolivian Minister of Human Resources, Franklin Anaya, a former ambassador in Havana and author of a comprehensive book on Cuba who acted as a liaison Bolivian. with Cuban anthropologists. “I had my suitcases packed,” Villoldo said.

ARRANGEMENT IN THE SEARCH OF THE REMAINS

Later, the media alleged that Anaya and Bolivian President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada had made a deal with Castro to favor the Cuban team. The accounts could not be confirmed, but Anaya suddenly canceled Villoldo’s plane reservations. Villoldo appealed to President Sánchez de Lozada and was again authorized to fly to Bolivia. But Bolivian friends advised him to stay in Miami, Villoldo said.

“My friends told me that Castro knew of my planned arrival and that there was some possibility that the Cubans would take action against me,” Villoldo said. “Based on the warning… I decided to wait and see what happened.”

What happened was a Cuban race to find the body.

Just 18 days after Villoldo’s letter reached Aleida Guevara, and a day after the municipal ban on excavating ended, the Cubans began a search for Che’s remains with an intensity never before seen in the last 16 months of excavation. They worked from sunrise to sunset, practically nonstop. They were in such a hurry that they used a digging tool considered anathema by all experts in their field: a bulldozer.

By June 27, a Cuban team led by Jorge González, head of Havana’s Institute of Legal Medicine, had dug several trenches and test pits in the area described by General Vargas, but turned up empty-handed. Time was running out.

The government of President Sánchez de Lozada ordered all excavations to stop on June 28, apparently due to the June 2 election of a new Bolivian president, Hugo Banzer. A former military dictator in the 1970s, Banzer is known to have little sympathy for Che, Castro, or Cuba. Sánchez de Lozada could have correctly assumed that his actions could be examined without sympathy by his successor.

Indeed, Banzer, who took office in August, promised to investigate his predecessor’s role in helping Cuba unearth Che’s remains and to investigate press reports that Anaya could personally benefit from the publicity rights to the history of the excavation.

QUICK SEARCH TO FIND THE REMAINS

Cuban excavators met until 4 o’clock in the morning on June 28 to decide where to focus their last day of excavation, recalled Alejandro Inchaurregui, one of a team of Argentine forensic anthropologists called to help the Cubans.

Ground radar surveys conducted by the Cuban-Argentine search team in early 1997 revealed a dozen points of disturbed ground that could be secret tombs, or perhaps displaced rocks or fallen trees. Of these, three, in particular, had all the characteristics of being man-made. This is where they got to work. With an excavator.

In the first place, they set the excavator’s blade to scrape four inches of dirt with each pass. Almost two hours later, they hit a rock and there is no sign of any bones. They moved up to No. 2. Eighteen scrapes from the bulldozer later, almost exactly six feet down, the blade uncovered, and it broke parts of a human skeleton.

What the Cubans had found were seven bodies, in two groups of three and four, 2 1/2 feet apart, buried in a well wedged between the old Vallegrande dirt track to the north and the nearby cemetery to the south.

The jubilation broke out when the second body was discovered, the middle in the group of three, and it was discovered that it had no hands. Che’s hands were amputated after his death as proof of his death.

But Che’s remains had yet to be officially identified by Bolivian government officials so they could be released and transferred to Cuba. “People from the Interior Ministry were telling us to move fast. As the Banzer inauguration approached, the screws were tightened,” Inchaurregui said.

And so, in the dead of night on July 5, a convoy of 10 vehicles made a five-hour, 150-mile race at breakneck speeds along dangerous mountain roads to transfer the wreckage to the provincial capital of Santa Cross.

There, the handless remains were quickly identified. The excavated teeth matched perfectly with a plaster cast of Che’s teeth made in Havana before leaving for the Congo so that he could be identified if he died in combat.

And there was a decisive factor, revealed to ‘Tropic’ by Jaime Nino de Guzmán, who had been a Bolivian army commander and helicopter pilot in 1967, and who had seen Che alive as a captive in La Higuera while transporting agents and supplies. in and out.

Che looked terrible, Nino de Guzmán recalled last month from his home in La Paz. He had been shot in the right calf, his hair was covered in dirt, it was shredded and his feet were covered with leather sheaths. But Che kept his head high, looked everyone in the eye, and only asked for something to smoke. He had rarely been seen without a Cuban cigar in hand after Castro triumphed, Che had switched to a pipe for guerrilla warfare.

“He pities me, he looked so terrible and I gave him my little bag of imported tobacco for his pipe. He smiled and thanked me,” the pilot recalled in a telephone interview.

Thirty years later, Inchaurregui said, he was inspecting a blue jacket unearthed alongside the handless remains when he found a small inside pocket, almost hidden and apparently missed by the soldiers who searched Che’s body. Hidden inside was a small bag of pipe tobacco.

“I must tell you that I had serious doubts at first. I thought that the Cubans would find old bones and call him Che,” Nino de Guzmán said. “But after hearing about the tobacco bag, I have no doubts.”

EUFORIA BEFORE THE IDENTIFICATION OF THE REMAINS OF THE “CHÉ” GUEVARA

“Just seeing the genuine emotion, the genuine euphoria on the faces of the Cubans there assures me that it is Che’s remains,” said John Lee Anderson, the American author. Anderson witnessed the final stages of the excavation. “They were just overwhelmed, crying and hugging.”

Recovering Che’s remains was a propaganda triumph for Castro, whose ideology has nearly collapsed since the collapse of the Soviet bloc.

Che was, literally, the poster boy for the Cuban Revolution. He was an Argentine-born asthmatic doctor who joined Castro in the war against the Batista dictatorship, then rejected Soviet orthodoxy and gave his life trying to export an ideology that he considered more humanitarian than communist. A five-story, 17-ton steel profile of Che covers the facade of the Ministry of the Interior headquarters in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución. It is a frequent backdrop to Fidel’s most important speeches, a virtual logo of the Cuban capital.

To this day, Che remains a global icon for radical change, his many political and economic mistakes, and his guerrilla defeats mostly forgotten and largely overshadowed by his enormous cultural impact. His romantic image, amplified by his untimely death and his unorthodox communism, allowed his appeal to transcend ideological lines.

.. Che has become a universal and multigenerational symbol of the 60s, like the Beatles, a man political enough to capture the politics of the time in a broad sense without getting bogged down in the whole Cold War theme. ” said Jorge Castaneda, a Mexican author of one of Che’s three biographies published that year. But Che’s story is also about money. Cuba bought 10,000 Swiss-made Swatch watches featuring Che’s bearded face and beard and sold them in boutiques in Havana. The then former Minister of Culture, Armando Hart, wrote a multimedia CD-ROM on Che, priced at $ 60.

Havana’s music historian Santiago Feliu has put together an anthology of 135 songs about Che, which will go on sale in October. Feliu said the songs will include traditional Cuban rhythms, as well as rock and blues, and some of whose lyrics are “ critical of those who have misused and vulgarized the image of Che. ”

Perhaps it refers to the Cuban street vendors who offer tourists the image of Che in everything from wood carvings to hammered leather and even dried sea grape leaves inscribed with some of his famous sayings.

It is doubtful that he is referring to the key chains, posters, and T-shirts with Che’s image that is always sold in Cuban government stores for $ 6 to $ 10 per postcard.

Cuba drew the marketing line for Che’s image last year, going after a British brewer who briefly brewed a “Che” beer with his image and the captivating slogan, “Banned in the US. Must be good.”.

Of course, certain Che artifacts, the authentic ones, like old rusty rifles, backpacks, and yellowed photographs found in Bolivia and quietly brought to Cuba by Cuban agents for years, cannot be mass-produced. But they can still be exploited.

That especially applies to Che’s latest artifact: his long-lost bones.

Even Gustavo Villoldo, who hunted Guevara around the world, now recognizes that these are probably Che’s remains. “Although I initially doubted it, all the evidence points to that,” he said after reviewing the evidence.

There is still another mystery, since the tomb where the Cubans found seven remains does not match the insignificant details of the tomb where Villoldo says he buried Che and two other guerrillas.

“I can’t explain that at all,” he said. “That was the most important moment of my life, and I can remember the details as if they were happening right now, right here. And they just don’t match.”

PLANS TO DISPOSAL OF THE REMAINS OF THE “CHE”

Villoldo learned of Che’s capture while he was at the Ranger’s forward command post in a nearby city. Villoldo rushed to Vallegrande, arriving on October 9, just two hours before the helicopter with Che’s body landed on a dirt airstrip packed with hundreds of journalists and curious people from the city.

“I never saw him alive, but I had no interest in that or talking to him,” he said. “It was never personal to me, even though the fact that Che had contributed to my father’s death was always in the back of my mind. It was just a job.”

The next day, October 10, the top Bolivian military commanders and Villoldo met at the restaurant of Vallegrande’s only hotel, the two-story Hotel Teresita, to discuss how to dispose of Che’s body, he recalled.

As in Che’s exhumation 30 years later, it was a race against the clock: the army officers had received the news that some of Che’s relatives were going to Vallegrande to claim the body.

But both Bolivians and Villoldo wanted to “disappear” him. “We thought it was important to dispose of it with maximum security to deny Castro the bones and the possibility of building some type of monument that could be exploited both ideologically and commercially,” Villoldo recalled.

Someone suggested cremating him, Villoldo said, but argued that in the absence of a true crematorium in Vallegrande, “all we would be doing would be holding a barbecue. I told them they had written a nice page in the history of the Bolivian army and that they shouldn’t end So”.

The army commanders eventually decided to amputate the hands for future identification and then secretly bury the body. The Chief of the Army, General Alfredo Ovando, assigned Villoldo to carry out the decisions. Villoldo was photographed by Bolivian journalists looking over the shoulders of the two doctors who performed a quick autopsy on the corpse and then, after the journalists left, amputated his hands.

It was then that Villoldo cut a lock of Che’s scruffy hair, at least initially for a green beret from the United States who had asked him for a souvenir. But, he sadly acknowledged, he kept some strings. “I don’t even remember if I cut it with a knife or scissors. I wasn’t interested and had no intention of keeping it. I’m not that kind of person. But over time, I thought, well…” He still has it, although he has never shown it in public.

Villoldo said he was provided with a security guard, a driver for a truck to transport the body, and a second driver for the bulldozer that would bury him.

QUESTIONS: A FINAL ENIGMA

He took a nap, woke up at 1:45 a.m., and went to the hospital laundry. Che’s body was lying on a sink. On the dirt floor, a couple of meters away, were the rapidly decomposing bodies of two other rebels.

It is the same scene described by the helicopter pilot Nino de Guzmán and by Alberto Suazo, who in 1967 when he was a young reporter for United Press International, saw Che’s body in the hospital. But Suazo recalled seeing “three or four other guerrilla corpses” somewhere in the courtyard behind the hospital, which is consistent with Guzmán’s account of flying on seven corpses.

Villoldo insists that he only saw Che and two other bodies.

He ordered his assistants to load the three bodies into the truck. They drove to the airstrip in total darkness until he saw a likely location near the walled cemetery of Vallegrande, Villoldo recalled. He told the driver to stop.

The site was south of the runway and west of the cemetery, in an area where a bulldozer had already been working nearby so that a new grave was not apparent, Villoldo says.

But the mass grave dug by the Cubans was north of the cemetery.

Villoldo says that while he sent one of his men to look for the excavator, he took compass readings and traveled distances from four points that would allow him to find the exact spot again. He didn’t write anything, he says, but he memorized the measurements.

They then backed the truck to the edge of a natural hole in the ground and unloaded the three bodies. Villoldo ordered the bulldozer driver to cover them. Both Villoldo and the excavator driver, who still lives in Vallegrande and was interviewed by Inchaurregui, recall that it began to rain towards the end of the burial.

The bulldozer driver said he did not remember exactly how many bodies he buried or whether the site was north or west of the cemetery. He can’t even say with certainty that Che was among the bodies, Inchaurregui told Tropic.

Inchaurregui said he believes Villoldo is lying or wrong by burying only three bodies. “Obviously he has political considerations to say what he says. It does not surprise me that after 30 years he is still trying to mislead everyone,” said the Argentine.

Villoldo’s CIA supervisor for the Bolivia mission, now retired in North Florida but still speaking only on condition of anonymity, said this: “Gus is not exaggerating. He would believe him if he said he buried three.”.

So how about those seven remains? Who were ‘Willy’ Simon Cuba Sarabia who helped Che when he was injured in the Quebrada de Yuro. Others were Orlando Tamayo “Antonio”; Aniceto Reynago Gordillo “Aniceto”; René Martínez Tamayo; Alberto Fernández Moisés de Oca “Pacho” and Juan Pablo Chang Navarro.

Could the truck or bulldozer drivers have buried the other four guerrillas earlier in the day and then brought an unconscious Villoldo to the same place to bury Che and the other two?

“No way. I told them where to go, where to stop. I chose the place alone,” said Villoldo.

Could the drivers have buried the other four bodies in the same place as Che and the other two the next day, perhaps returning to where they had left the bulldozer after the rains?

Not likely, Inchaurregui said. The pattern of excavation marks in the pit from which the seven bodies were dug indicated that an excavator had dug it with back and forth passes, not simply moving dirt over the bodies naturally as Villoldo described.

Analysis of the hardness of the dirt also showed that the tomb had a common compact earth floor under all the bodies and that all seven bodies had been covered with the same dirt at the same time, Inchaurregui added.

“It seems to be an opening and a closing of the tomb. There are seven bodies, not three. That is the empirical evidence,” concluded the anthropologist.

Could Villoldo, by a trillion to one coincidence, have buried the three bodies in the same wilderness where some Bolivian army officer had previously dumped four unburied corpses?

“I looked at that and didn’t see anything,” said Villoldo. “I buried and covered three bodies. I know for sure. I never saw seven bodies, I didn’t even know about seven bodies until much later.”

Today, a small team of Cubans working at a slower pace remains in Vallegrande, searching for some 23 more guerrilla corpses believed to be buried in unmarked graves in the region.

The body of the second most notorious guerrilla is still missing: Tamara Bunker, a beautiful young Argentinean of German descent named Tanya, a reputed KGB agent.

Villoldo remains determined to fly to Bolivia to visit the site where the handless remains were unearthed and compare it with the directions and distances he recorded the night he buried Che.

Meanwhile, Villoldo takes care of his farm, studies the large-scale maps of Vallegrande, re-reads his books on Che, and tries to discover how it is possible to bury three bodies and unearth seven.

“Maybe you can head this story Che: The end of the myth,” he suggested.

Agencies/ The Herald/ N. Tamayo/ G.Villoldo/ Extractos/ Excerpts/ Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ www.TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.