LA LARGA HISTORIA HACIA EL RECONOCIMIENTO DE LAS IDENTIDADES AFRO-CUBANAS.

LA LARGA HISTORIA HACIA EL RECONOCIMIENTO DE LAS IDENTIDADES AFRO-CUBANAS.

Paradójicamente, fue dentro de los cabildos patrocinados por la iglesia que las religiones e identidades afrocubanas se unieron. Incluso después de que se disolvieron oficialmente a fines del siglo XIX, muchos se mantuvieron informales y fueron conocidos popularmente por sus antiguos nombres africanos. Algunos sobreviven hasta nuestros días. Los cabildos no solo conservaron prácticas africanas específicas, sino que sus miembros también reunieron y sintetizaron creativamente muchas tradiciones regionales africanas, algunas, como en el caso de Yoruba, separadas durante mucho tiempo por la migración y la guerra.

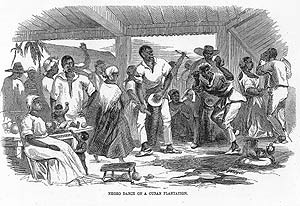

Mientras que los cabildos formalmente organizados eran un fenómeno principalmente urbano, las prácticas africanas individuales y colectivas también continuaron floreciendo en las haciendas azucareras, conocidas como ingenios o centrales. Estos eran más como pequeños municipios industriales autónomos que “plantaciones”. Alrededor del 80% de los recién llegados [africanos] conocidos como bozales, fueron enviados a ellos, y muchas centrales se convirtieron en centros de “naciones” africanas específicas.

Forjados en los cabildos y en medio de la ardua labor de los ingenios azucareros, cuatro importantes divisiones afrocubanas (Lucumí, Arará, Abakuá, Kongo) están representadas en Cuba.

Comenzamos con:

La transformación de Cuba en una isla azucarera está íntimamente vinculada a través de la trata de esclavos a la historia africana. Coincidió con el colapso del imperio Oyo de Nigeria después de décadas de conflicto interno entre los Yoruba y la guerra con sus vecinos Fulani al norte y los Dahomeans al oeste. Muchos Yoruba fueron llevados a Cuba muy tarde en el comercio de esclavos, especialmente durante los años 1820-1840, cuando formaron la mayoría de los [africanos] enviados a través del Atlántico desde los puertos de la Bahía de Benin. Incluían varios subgrupos de habla yoruba, incluyendo Ketu, Ijesha, Egbado, Oyo, Nago y otros.

En Cuba, los hablantes de yoruba se hicieron conocidos por el término colectivo Lucumí, después de una frase en yoruba, oloku mi, que significa mi amigo. Como resultado de la esclavitud, los linajes y grupos de parentesco que habían apoyado la adoración de los diversos orisha se vieron afectados. Surgió una nueva religión llamada santería, que agrupaba a muchos orisha, cada uno de los cuales se identificaba con un santo católico en cuyo día se celebraban las fiestas. Desde los cabildos étnicos de la Cuba colonial, la santería se organizó en “casas” individuales, conocidas como casas de ocha. Desde entonces se ha extendido mucho más allá de su base étnica original, tanto dentro como fuera de Cuba.

La entrada a la santiería es a través de un largo proceso de iniciación, durante el cual un orisha está sentado en la cabeza de un iyawó, o iniciado. Al igual que en otras religiones basadas en África en las Américas, la música desempeña un papel fundamental al hacer que los orishas bailen en las cabezas de los iniciados, y en la creación y el mantenimiento del entorno ritual. Los instrumentos más sagrados entre los Lucumí son el trío de tambores batá, que cuando se consagran se llaman fundamento y se dice que tienen una deidad residente llamada Añá. Los batá se juegan en las ceremonias de iniciación, en las presentaciones de los iniciados a los tambores, en los funerales, en las ceremonias en honor a los antepasados y en otras que requieren tambores sacralizados. Otros estilos de Lucumí incluyen conjuntos de calabazas con cuentas, conocidas como abwe o chekeré, que se juegan, por ejemplo, en ceremonias que celebran rituales “cumpleaños”; y conjuntos de tambores bembé, generalmente de forma cilíndrica, que pueden mostrar influencias no yoruba y se encuentran generalmente en áreas rurales.

En la década de 1950 hubo una mayor infusión de estilos rituales y temas de Lucumí en la corriente principal de la música popular cubana. Un evento importante fue el lanzamiento de un LP llamado Santero, que contó con bateristas de batá del área de La Habana y cantantes populares como Mercedes Valdés, Celia Cruz y otros, todos cantando en Lucumí. Celia Cruz y Gina Martin también grabaron canciones en formato conjunto que fueron homenajes a diferentes orishas. Más recientemente, el grupo cubano Mezcla, con el gran akpon (el líder de la canción de Lucumí) Lázaro Ros, ha estado grabando una nueva música ritual popular, algunas al estilo del zouk caribeño francés, algunas influenciadas por el jazz y el rock.

Los batá son un conjunto de tres tambores de doble cabeza con forma de reloj de arena. El iyá más grande (madre), [E-Yah], es el tambor maestro. El iyá llama a los ritmos, llama a los cambios y las conversaciones. A continuación en tamaño, el itótele (significa: sigue completamente), [E-Toe-Teh-Lay], sigue la dirección del iyá respondiendo a las llamadas de conversación y los cambios de ritmo. El tambor más pequeño okónkolo [O-Kon-Ko-Lo], a veces denominado Omele [O-May-Lay (niño fuerte)], en su mayor parte toca patrones de ostinato, y también cambia los ritmos de las llamadas del iyá.

Los Iyesá son una “nación” lucumí que todavía se reconoce por tener un estilo musical distinto. Los tambores de Iyesá se tocan con palos, generalmente en grupos de tres, con un cuarto tambor agregado para ciertos toques. Sus patrones rítmicos combinados están más unificados que la conversación de tres vías entre los tambores batá. Agogó, o gongs de baile, de diferentes tonos que tocan patrones entrelazados acompañan a estos tambores.

El último Iyesá cabildo sobreviviente en Cuba es San Juan Bautista, que fue fundado en 1854 en la ciudad de Matanzas.

THE LONG HISTORY TO THE RECOGNITION OF IDENTITIES AFRO-CUBANAS.

THE LONG HISTORY TO THE RECOGNITION OF IDENTITIES AFRO-CUBANAS.

Paradoxically, it was within the church sponsored cabildos that Afro-Cuban religions and identities coalesced. Even after they were officially disbanded at the end of the 19th century, many were kept up on an informal basis, and were known popularly by their old African names. Some survive to this day. The cabildos not only preserved specific African practices, their members also creatively reunited and resynthesized many regional African traditions, some, as in the case of the Yoruba, long separated by migration and war.

While the formally organized cabildos were a primarily urban phenomenon, individual and collective African practices also continued to flourish at the sugar estates, known as ingenios or centrales. These were more like small, self-contained industrial townships than “plantations.” About 80% of the newly-arrived [Africans] known as bozales, were sent to them, and many centrales became centers of specific African “nations.”

Forged in the cabildos and amidst the grueling labor at the sugar mills, four major Afro-Cuban divisions (Lucumí, Arará, Abakuá, Kongo) are represented in Cuba.

We’ll start with:

Cuba’s transformation into a sugar-growing island is intimately linked via the slave trade to African history. It coincided with the collapse of the Oyo empire of Nigeria after decades of internal strife among the Yoruba and warfare with their Fulani neighbors to the north and Dahomeans to the west. Many Yoruba were taken to Cuba very late in the slave trade, especially during the years 1820-1840, when they formed a majority of [Africans] sent across the Atlantic from the ports of the Bight of Benin. The included several Yoruba-speaking subgroups, including the Ketu, Ijesha, Egbado, Oyo, Nago and others.

In Cuba, Yoruba speakers became known by the collective term Lucumí, after a Yoruba phrase, oloku mi, meaning my friend. As a result of slavery, the lineages and kin groups that had supported worship of the various orisha were disrupted. A new religion called santería arose, which grouped together many orisha, each of which became identified with a Catholic saint on whose day festivals would be held. From the ethnically-based cabildos of colonial Cuba, santería became organized into individual “houses,” known as casas de ocha. It has since spread far beyond its original ethnic base, both within and outside of Cuba.

Entry into santiería is through a long process of initiation, during which an orisha is seated in the head of an iyawó, or initiate. As in other African-based religions in the Americas, music plays a critical role in bringing the orisha to dance in the heads of the initiates, and in creating and sustaining the ritual setting. The most sacred instruments among the Lucumí are the trio of batá drums, which when consecrated are called fundamento and are said to hold an indwelling deity called Añá. Batá are played at initiation ceremonies, in the presentations of initiates to the drums, at funerals, in ceremonies honoring the ancestors and in others that call for sacralized drums. Other Lucumí styles include ensembles of beaded gourds, known as abwe or chekeré, which are played, for example, in ceremonies celebrating ritual “birthdays;” and sets of bembé drums, usually cylindrical in shape, which may show non-Yoruba influences and are usually found in rural areas.

In the 1950s there was an increased infusion of Lucumí ritual styles and subject matter into the Cuban popular music mainstream. One important event was the release of an LP called Santero, which featured batá drummers from the Havana area and such popular singers as Mercedes Valdes, Celia Cruz and others, all singing in Lucumí. Celia Cruz and Gina Martin also recorded songs in conjunto format that were homages to different orisha. More recently, the Cuban group Mezcla, featuring the great akpon (Lucumí song leader) Lázaro Ros, has been recording a new ritual-popular music, some in the style of French Caribbean zouk, some influenced by jazz and rock.

Batá are a set of three double-headed, hourglass-shaped drums. The largest iyá (mother), [E-Yah], is the master drum. The iyá calls the rhythms in, calls changes and conversations. Next in size, the itótele (means: follows completely), [E-Toe-Teh-Lay], follows the direction of the iyá answering the conversation calls and rhythm changes. The smallest drum okónkolo [O-Kon-Ko-Lo], sometimes referred to as Omele [O-May-Lay (strong child)], , for the most part plays ostinato patterns, also changing rhythms from the calls of the iyá.

The Iyesá are a Lucumí “nation” still recognized as having a distinct musical style. Iyesá drums are played with sticks, usually in groups of three, with a fourth drum added for certain toques. Their combined rhythmic patterns are more unified than the three-way conversation among the batá drums. Agogó, or dance gongs, of different pitches that play interlocking patterns accompany these drums.

The last surviving Iyesá cabildo in Cuba is San Juan Bautista, which was founded in 1854 in the City of Matanzas.

Agencies/ African Links/ Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ www.TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.