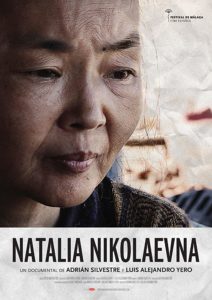

LA DESDICHADA VIDA DE NATALIA NIKOLAEVNA. UNA MUJER RUSA EN CUBA.

Natalia Nikolaevna vive a 400 km de La Habana, en la ciudad donde se construiría la primera central electro nuclear de Cuba. Llegó hace 20 años desde la URSS, para reencontrarse con su esposo un joven estudiante cubano de Ingenieria en la entonces Union Sovietica. Una mujer kazaja que a fines de los ochenta conoció y llegó a Cuba con su recien esposo cubano repletos de ímpetus e ilusiones, nada menos que en la Ciudad Nuclear, un rincón de Cienfuegos en el que Fidel Castro comenzó a construir con la ayuda de los soviéticos una imponente Central Electronuclear, hasta que todo se fue a pique.

Un documental filmado por medio hora por el periodista Alejandro Yero llena de estupor. El documental, rodado en 2012-2013, comienza con varios planos generales y una música claramente influenciada por el Philip Glass de Koyaanisqatsi. Se observan los edificios vacíos, las construcciones a medio hacer, armatostes de cemento deshabitados, los parques yermos, las calles desoladas, algún perro que cojea, alguna sombra en la distancia. Pero si en Koyaanisqatsi el mundo está en constante actividad, aquí está completamente muerto, o con un hilillo de vida. Todo excesivamente triste. También se ve el mar, los barcos oxidados por el salitre, arañazos de luz solar recorriendo la superficie del agua. El horror es inminente. La amargura es inminente. La estolidez es inminente también.

https://vimeo.com/146836698

No solo no puede cantar ya, sino la han borrado de los anales, desaparecido de un plumazo sin explicación ni causa posible.

Natalia es una mujer menuda. Cómicas botas negras, pantorrillas robustas, un largo vestido de rayas anchas y el pelo recogido en un moño flácido. Parece una koljosiana. En su momento, Natalia fue contratada por la Empresa de Cultura de Cienfuegos para cantar lírico en la capital provincial. Y, dice, cantó. Pero ya no canta. Y no se explica por qué. De hecho, el documental, aunque también tiene muchos otros rostros que luego irán emergiendo como epifanías terribles o como muecas insoportables o como rictus agónicos, en principio no parece ser más que la cruzada de Natalia por volver a cantar y porque le restituyan su pasado. No solo no puede cantar ya, sino, dice Natalia, la han borrado de los anales, desaparecido de un plumazo sin explicación ni causa posible.

Tiene una libreta con la firma de setenta y cinco músicos de la localidad que ella ha conocido a lo largo de los años, con los que ha colaborado, y que acudieron en su defensa. Ha recorrido todas las instituciones cienfuegueras y la fiscalía de la ciudad le ha confesado no encontrar ninguna prueba de que ella realmente haya sido cantante lírica. Natalia dice haber hallado su expediente laboral falsificado. Guarda, además, un recorte del periódico local 5 de septiembre. Son solamente dos palabras, pero son de mucha calidad y muy cariñosas, dice, esbozando una sonrisa o bien riéndose a mandíbula batiente. “Nuestra soprano Natalia, invitada especial de la segunda noche”, se lee en el recorte de prensa. Entonces, dice Natalia, ¿hay pruebas o no hay pruebas de que Natalia Nikolaevna fue cantante lírica?

No hay dinero, pero ya tenemos repertorio suficiente.

Su acento es particularmente gracioso. Su acento, casi un trino, es seductor, como si el acento dijera todo por sí mismo. Resulta evidente que el drama de Natalia es aún más drama por el acento con que lo cuenta, o que es drama únicamente por el acento con que lo cuenta, un acento kazajo, deslavado, contrito, lo cual, por oposición, viene a decirnos que el acento del cubano no es un acento idóneo para la tragedia, tal vez para cualquier otra cosa sí, pero no para el terreno del sufrimiento y la penuria. En el conteo universal del drama, el acento cubano no cuenta y, por lo mismo, el drama cubano no cuenta y, mientras no encuentren otro tono para relatar su travesía, sus dudas sobre el futuro, sus traumas del pasado, el drama y el acento cubano, los dos por igual, seguirán mereciendo la más burlesca de las trompetillas o el más humillante y merecido ninguneo.

En las mañanas, Natalia atraviesa en una lancha de pasajeros la bahía de Cienfuegos y en la glorieta de la ciudad canta algunas arias de Rossini, Donizetti o Verdi. Como el brindis de La Traviata, por decir lo obvio. Algunos turistas o alguna pareja de recién casados la escuchan y le donan algunas monedas. Algunos viejos indigentes también la escuchan. Quien inauguró el canto lírico en Cienfuegos, a comienzo del siglo XX, fue Caruso, dice Natalia, y quien lo inauguró en la Ciudad Nuclear fue Natalia Nikolaevna. Durante las tardes, Natalia ensaya con el organista de la iglesia, un muchacho joven que no le presta mucha atención, aun cuando Natalia lo anime a organizar un concierto. Un concierto particular, dice, no importa que no nos apoyen. No hay dinero, pero ya tenemos repertorio suficiente, dice, y así nosotros nos animamos también. En realidad, Natalia ya está animada, no parece que el ánimo se le vaya a esfumar, al menos no a corto o mediano plazo. Pero el organista sí luce un tanto pesimista y Natalia, que no es tonta, se percata. Le preocupa quedarse sin acompañante.

Esta fue mi ayuda para sobrevivir en el Período Especial, dice Natalia, y enseña a la cámara una báscula. Natalia, la solista lírica de Cienfuegos, andaba por la calle con esto para poder sobrevivir, dice. La gente se pesaba por una cantidad de dinero. Llegué desde cincuenta quilos a cinco pesos. Un peso primero, dos después. Y así. Pero los funcionarios del Poder Popular, dice, me prohibieron terminantemente seguir pesando personas. Natalia suelta una carcajada contagiosa. Y yo estoy de acuerdo con ellos, dice, quizás en el momento más sublime del documental. Yo esto de acuerdo con ellos, porque una cantante lírica soprano no tiene por qué andar pesando gente por ahí.

Hay algo más que Natalia enseña a la cámara. Y es esto: el certificado de discapacitada con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia paranoica. En una exposición de la galería municipal, Natalia observa los cuadros de los artistas locales y se detiene en un tornillo de banco que, entre sus quijadas, sostiene un huevo. Esa soy yo, dice. Yo digo que yo soy tan frágil que no hace falta tanta maquinaria para romperme ni para sostenerme ni nada. Yo me siento muy identificada con eso, esa soy yo, y realmente pienso que no tengo futuro en Cuba porque tengo unas personas que están tratando de matarme. Hay peligro para mi salud desde hace tiempo y están detrás de mí con las sustancias para afectar mis cuerdas vocales. Usted es cubano —le dice probablemente a Alejandro, que la filma—, usted sabe que los envenenamientos ocurren en la sociedad cubana.

THE SAD LIFE OF NATALIA NIKOLAEVNA. A RUSSIAN WOMAN IN CUBA.

THE SAD LIFE OF NATALIA NIKOLAEVNA. A RUSSIAN WOMAN IN CUBA.

Natalia Nikolaevna lives 400 km from Havana, in the city where the first Cuban nuclear power plant would be built. She arrived 20 years ago from the USSR, to reunite with her husband, a young Cuban engineering student in the then Soviet Union. A Kazakh woman in the late eighties arrived in Cuba with her new Cuban husband full of impetus and illusions, no less than in the Nuclear City, a corner of Cienfuegos where Fidel Castro began to build with the help of the Soviets an imposing Electronuclear Power Plant until everything fell apart.

A documentary film for half an hour by the journalist Alejandro Yero is full of amazement. The documentary, shot in 2012-2013, begins with several wide shots and music clearly influenced by Philip Glass of Koyaanisqatsi. You can see the empty buildings, the half-built buildings, uninhabited cement huts, the barren parks, the desolate streets, some limping dog, some shadow in the distance. But if in Koyaanisqatsi the world is in constant activity, here it is completely dead, or with a thread of life. All excessively sad. You can also see the sea, the ships rusted by nitrate, scratches of sunlight crossing the surface of the water. Horror is imminent. Bitterness is

imminent. Stolidity is imminent too.

https://vimeo.com/146836698

Not only can she no longer sing, but she has been erased from the annals, disappeared with the stroke of a pen without explanation or possible cause.

Natalia is a petite woman. Comical black boots, sturdy calves, a long, wide-striped dress, and her hair tied back in a limp bun. She looks like a Kolkhoz. At the time, Natalia was hired by the Cienfuegos Culture Company to sing lyric in the provincial capital. And, she says, she sang. But she doesn’t sing anymore. And it is not explained why. In fact, the documentary, although it also has many other faces that will later emerge as terrible epiphanies or as excruciating grimaces or as agonizing rictus, at first seems to be nothing more than Natalia’s crusade to sing again and to restore her past. Not only can she no longer sing, but, says Natalia, they have erased her from the annals, disappeared with a stroke of the pen without explanation or possible cause.

She has a notebook with the signature of seventy-five local musicians that she has known over the years, with whom she has collaborated, and who came to her defense. She has toured all the institutions in Cienfuegos and the city prosecutor’s office has confessed to finding no evidence that she really was a lyrical singer. Natalia claims to have found her falsified employment record. It also has a clipping from the local newspaper on September 5. They are only two words, but they are of very high quality and very affectionate, he says, with a smile or a chuckle. “Our soprano Natalia, special guest of the second night”, reads in the press clipping. So, says Natalia, is there evidence or no evidence that Natalia Nikolaevna was a lyrical singer?

There is no money, but we already have enough repertoire.

Her accent is particularly funny. Her accent, almost a trill, is seductive as if the accent said everything by itself. It is evident that Natalia’s drama is even more drama because of the accent with which she tells it, or that it is drama only because of the accent with which she tells it, a Kazakh accent, washed out, contrite, which, by the opposition, comes to tell us that the accent of the Cuban is not an ideal accent for tragedy, perhaps for anything else, but not for the terrain of suffering and hardship. In the universal count of the drama, the Cuban accent does not count and, therefore, the Cuban drama does not count and, until they find another tone to relate their journey, their doubts about the future, their traumas of the past, the drama and the Cuban accent, both equally, will continue to deserve the most burlesque of the trumpets or the most humiliating and deserved none.

In the mornings, Natalia crosses the bay of Cienfuegos in a passenger boat and sings some arias by Rossini, Donizetti or Verdi in the city gazebo. Like the toast of La Traviata, to say the obvious. Some tourists or a newly married couple listen to her and donate some coins. Some destitute old men also listen to her. The one who inaugurated lyrical singing in Cienfuegos, at the beginning of the 20th century, was Caruso, says Natalia, and the one who inaugurated it in the Nuclear City was Natalia Nikolaevna. During the afternoons, Natalia rehearses with the church organist, a young boy who doesn’t pay much attention to her, even when Natalia encourages him to organize a concert. A particular concert, he says, does not matter that they do not support us. There is no money, but we already have enough repertoire, she says, and so we are encouraged too. In reality, Natalia is already animated, it does not seem that her spirits are going to fade, at least not in the short or medium term. But the organist does look somewhat pessimistic and Natalia, who is not stupid, notices. You are concerned about being unaccompanied.

This was my help to survive in the Special Period, says Natalia, and shows the camera a scale. Natalia, the lyrical soloist from Cienfuegos, walked down the street with this in order to survive, she says. People weighed themselves for an amount of money. I went from fifty kilos to five pesos. One weight first, two later. And so. But Popular Power officials, he says, strictly prohibited me from continuing to weigh people. Natalia lets out a contagious laugh. And I agree with them, he says, perhaps at the most sublime moment in the documentary. I agree with them because a lyric soprano singer does not have to go around weighing people.

There is something else that Natalia teaches the camera. And it is this: the certificate of disabled with a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. In an exhibition at the municipal gallery, Natalia observes the paintings of local artists and stops at a vice that, between her jaws, holds an egg. That’s me, he says. I say that I am so fragile that it does not take so much machinery to break me or to support me or anything. I feel very identified with that, that’s me, and I really think that I have no future in Cuba because I have some people who are trying to kill me. There is a danger to my health for a long time and they are behind me with substances to affect my vocal cords. You are Cuban – he probably tells Alejandro, who is filming it – you know that poisonings occur in Cuban society.

Agencies/ Carlos M. Alvarez/ Alejandro Yero/ Extractos/ Excerpts/ Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ www.TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.