AQUEL SABADO, 10 DE OCTUBRE EN LA DEMAJAGUA, CUBA. PHOTOS.

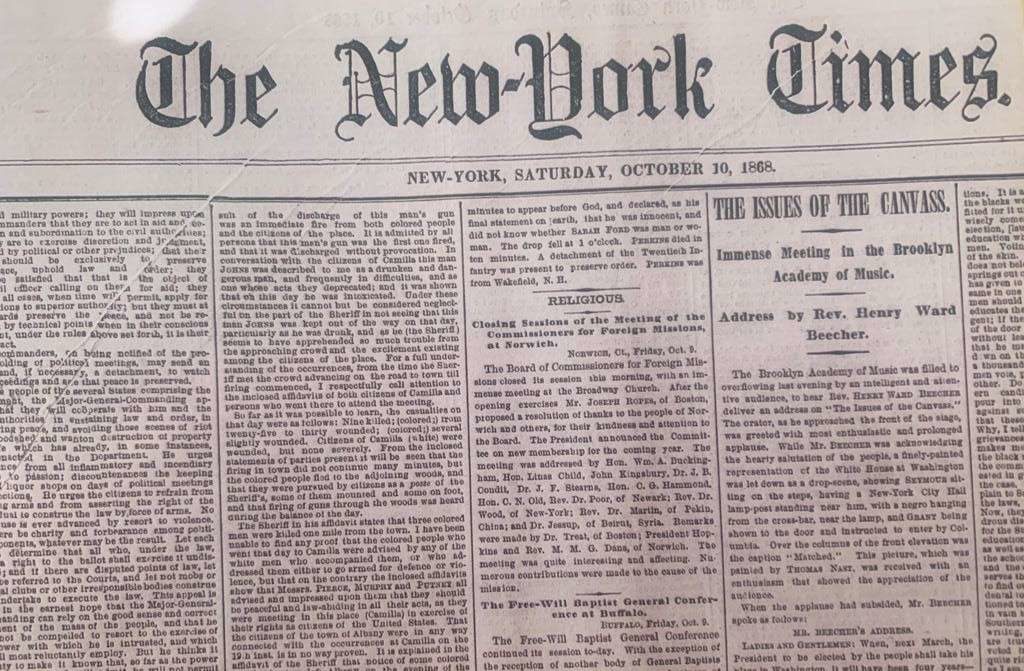

Ese dia en la sección “Telegramas”, la noticia sobre el levantamiento ocurrido en Cuba fue descripto por el Diario Norteamericano “The New York Times” en forma de titular, sin otros comentarios: “Reported Declaration for Independence by Cuba”. Así, simplemente.

HASTA LA SACIEDAD ha sido examinado por los historiadores lo ocurrido el 10 de octubre de 1868 en el ingenio Demajagua, perteneciente al abogado y hacendado Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. Sin embargo, se mantuvieron por mucho tiempo vacíos de información en cuanto a lo sucedido ese día. El informe redactado por Bartolomé Masó, —lugarteniente de Céspedes—, aparecido poco después del 10 de octubre, ayudó de manera determinante a clarificar estos hechos. En dicho reporte, titulado “Parte del pronunciamiento efectuado en Demajagua, en Manzanillo, el diez de octubre de 1868, y primer encuentro de Yara con las tropas españolas…”, se puede leer de puño y letra de Masó:

“Como a las 10 del día nos encontrábamos congregados en aquel ingenio sobre quinientos patriotas, mandados a formar por el General en Gefe (sic) se dio ¡El Grito de Independencia! Enarbolándose el Estandarte que la simboliza, a cuya sombra prestaron todos el juramento solemne de vencer o morir, antes que volver a ver hollado el suelo de la Patria por ninguna de las tiranías. El General en Gefe reunió sus esclavos y los declaró libres desde aquel instante, invitándoles para que nos ayudasen si querían, a conquistar nuestras libertades; lo mismo hicieron con los suyos los demás propietarios que le rodeabamos….” (Tomados directamente asi).

Gracias a este documento y a otros testimonios se ha podido conocer, además, que los rebeldes se mantuvieron en Demajagua durante el resto de ese día y partieron en la madrugada del domingo 11 de octubre hacia Yara, donde libraron el primer encuentro armado con las fuerzas españolas. De ahí que al pronunciamiento se le llamó por mucho tiempo “Grito de Yara”, cuando en realidad se debió llamar “de la Demajagua”. Puedo imaginar los apremios de aquel sábado e incluso el arribo de los complotados al ingenio las fechas previas, el 8 y 9 de octubre. Fue un escenario de gran ajetreo, de salida y llegada de emisarios desde y hacia los otros conjurados, con vertiginosas acciones y aprestos, de discusiones entre los jefes sobre rumbos y acciones a seguir, así como de otras cuestiones relativas al contenido político y militar de la insurrección.

Allí se organizaron las bisoñas tropas que constituirían el destacamento inicial del Ejército Libertador; y se dio lectura al Manifiesto de la Junta Revolucionaria de la Isla de Cuba, nuestra declaración de independencia. También se mostró la enseña que guiaría las acciones bélicas, además de que Céspedes protagonizara su gran gesto simbólico de otorgarle la libertad a sus esclavos, a la vez que los invitaba a luchar por Cuba. A ellos les habló el amo de esclavos la noche del 9 de octubre y les pidió que tocaran la tumba francesa para celebrar lo que ya todos sabían que ocurriría al día siguiente: la insurrección.

El día 6 de ese mes, el grupo de manzanilleros liderados por Céspedes se reunió en el ingenio El Rosario, de Jaime Santiesteban, para determinar que el 14 de octubre se alzarían en los montes contra el poder colonial. Holguineros, camagüeyanos y santiagueros no estaban de acuerdo con la fecha y pidieron tiempo para adquirir armamento, pero ante la presión de Céspedes y los jefes tuneros finalmente aceptaron la decisión. La fecha del 14 fue adelantada al recibir Céspedes copia de un telegrama del Capitán General español en que ordenaba la detención de los conjurados, él entre ellos. De esa forma se decidió, con apremio, la nueva fecha del 10 de octubre. En la reunión de El Rosario se levantó un acta, que fue una verdadera declaración de independencia y que, comparada con el Manifiesto leído por Céspedes en la mañana del 10 de octubre, da la idea de que aquella pudo muy bien ser el borrador de este.

NOTICIAS DEL LEVANTAMIENTO…

Mientras que la prensa estadounidense publicaba el titular el mismo día del levantamiento, la prensa española insular lo dio a conocer el 13 de octubre. Según La Gaceta Oficial, se había producido una insurrección en el Oriente del país: “Según telegramas oficiales de Yara, jurisdicción de Manzanillo, se levantó el día 10 una partida de paisanos, sin que se hasta ahora se sepa el cabecilla que los manda ni el objeto que la conduce…”. Como se puede apreciar, el nombre de Yara y no Demajagua es el que se maneja por el periódico.

Lo demás es bien conocido. En Yara los patriotas sufrieron su primera derrota, en un breve enfrentamiento que produjo las primeras bajas —de ambas partes— de la guerra y Céspedes ordenó la retirada en vista de que los españoles habían llegado primero al poblado y ocupado ventajosas posiciones defensivas. La retirada fue hacia Palmas Altas, donde se reunieron con otras tropas levantadas y donde se reestructuró el incipiente Ejército Libertador; también allí Bartolomé Masó dispuso de cierta calma para redactar su informe. Desde ese punto se dirigieron a Bayamo, la que fue ocupada tras tres días de fieros combates, el 20 de octubre, lo que permitió que Céspedes pudiese establecer por ochenta y tres días la capital de la insurrección.

Así comenzó todo ese largo proceso revolucionario que hoy todavia grita por efectuarse contra otra tirania en nuestra Patria. Otro 10 de Octubre patriotico, pero esta vez será a todo lo largo de la nación.

THAT SATURDAY, OCTOBER 10, IN LA DEMAJAGUA, CUBA. PHOTOS.

That day in the “Telegrams” section, the news about the uprising that took place in Cuba was described by the American newspaper “The New York Times” in the form of a headline, without other comments: “Reported Declaration for Independence by Cuba”. Just like that.

UNTIL SATISFYING has been examined by historians what happened on October 10, 1868, at the Demajagua sugar mill, belonging to the lawyer and landowner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. However, they remained for a long time empty of information regarding what happened that day. The report written by Bartolomé Masó, —Céspedes’ lieutenant—, which appeared shortly after October 10, decisively helped to clarify these facts. In the said report, entitled “Part of the pronouncement made in Demajagua, in Manzanillo, on October 10, 1868, and Yara’s first meeting with the Spanish troops…”, it can be read in Masó’s own handwriting:

“Around 10 o’clock in the morning, we have gathered in that mill about five hundred patriots, ordered to form by the General in Chief (sic) The Cry of Independence was given! Hoisting the Standard that symbolizes it, in whose shadow they all swore the solemn oath to win or die, rather than see the soil of the Homeland trampled again by any of the tyrannies. The General in Chief gathered his slaves and declared them free from that moment, inviting them to help us if they wanted, to conquer our freedoms; The other owners around him did the same with theirs….” (Taken directly like this).

Thanks to this document and other testimonies, it has also been possible to know that the rebels remained in Demajagua for the rest of that day and left at dawn on Sunday, October 11, for Yara, where they fought the first armed encounter with the Spanish forces. . Hence, the pronouncement was called “Grito de Yara” for a long time, when in reality it should have been called “de la Demajagua”. I can imagine the pressures of that Saturday and even the arrival of the conspirators at the mill on the previous dates, October 8 and 9. It was a scene of great hustle and bustle, of departure and arrival of emissaries to and from the other conspirators, with vertiginous actions and preparations, of discussions between the chiefs about directions and actions to follow, as well as other questions related to the political and military context of the insurrection.

There the inexperienced troops that would constitute the initial detachment of the Liberation Army were organized; and the Manifesto of the Revolutionary Junta of the Island of Cuba, our declaration of independence, was read. The banner that would guide the war actions was also shown, in addition to Céspedes starring in his great symbolic gesture of granting freedom to his slaves, while inviting them to fight for Cuba. The slave master spoke to them on the night of October 9 and asked them to touch the French tomb to celebrate what everyone already knew would happen the next day: the insurrection.

On the 6th of that month, the group of manzanilleros led by Céspedes met at Jaime Santiesteban’s El Rosario sugar mill to determine that on October 14 they would rise up in the mountains against the colonial power. Holguin, Camagüey, and Santiago residents did not agree with the date and asked for time to acquire weapons, but under pressure from Céspedes and the Las Tunas chiefs, they finally accepted the decision. The date of the 14th was brought forward when Céspedes received a copy of a telegram from the Spanish Captain General in which he ordered the arrest of the conspirators, himself among them. In this way, the new date of October 10 was decided, with urgency. At the meeting in El Rosario, a minute was drawn up, which was a true declaration of independence and which, compared to the Manifesto read by Céspedes on the morning of October 10, gives the idea that it could very well have been the draft of this.

NEWS OF THE UPRISING…

While the US press published the headline on the day of the uprising, the insular Spanish press published it on October 13. According to the Official Gazette, an insurrection had taken place in the eastern part of the country: “According to official telegrams from Yara, the jurisdiction of Manzanillo, a party of civilians rose up on the 10th, without the ringleader who commands them being known or unknown. the object that drives it…” As can be seen, the name Yara and not Demajagua is the one used by the newspaper.

The rest is well known. In Yara, the patriots suffered their first defeat, in a brief confrontation that produced the first casualties —on both sides— of the war, and Céspedes ordered a withdrawal in view of the fact that the Spaniards had reached the town first and occupied advantageous defensive positions. The withdrawal went to Palmas Altas, where they met with other raised troops and where the incipient Liberation Army was restructured; Bartolomé Masó also had a certain amount of calm there to write his report. From that point, they went to Bayamo, which was occupied after three days of fierce fighting, on October 20, which allowed Céspedes to establish the capital of the insurrection for eighty-three days.

Thus began the entire long revolutionary process that today still cries out for being carried out against another tyranny in our country. Another patriotic October 10, but this time it will be across the nation.

Agencies/ OnCuba/ Rafael Acosta/ 10deOctubreHist./ Extractos/ Excerpts/ Internet Photos/ Arnoldo Varona/ www.TheCubanHistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.

AQUEL SABADO, 10 de Octubre en la Demajagua, Cuba. PHOTOS. * THAT SATURDAY, October 10 in La Demajagua, Cuba. PHOTOS.

AQUEL SABADO, 10 de Octubre en la Demajagua, Cuba. PHOTOS. * THAT SATURDAY, October 10 in La Demajagua, Cuba. PHOTOS.