Monte’s Causeway is called Máximo Gómez, and Reina is named after Simón Bolivar. Finlay Street was the Old street Zanja, and Belascoaín called Father Varela. But how many in La Havana, old or young, refer to those pathways for its official nomenclature? Few indeed, although the documents and tablets that identify insist on reminding us that Teniente Rey, Zulueta, Concha y Estrella are called Brazil, Agramonte, Ramon Pinto and Henry Barnet, respectively.

Have you even begun to think of the street that bears his name and why? Some are identified by letters, sometimes with numbers. That way as rational to distinguish the streets began to be used here since 1858 when the ranch El Carmelo became a residential area. It comprised 105 blocks that lie between the river Almendares and the current Paseo Street and from 21 Street to the coastline.

This land became more important a year later, when the Count of Pozos Dulces and his sisters were authorized to divide up his estate was divided El Vedado and in the 29 blocks that extend from the streets G and 9 to the borders of El Carmelo . That’s when the block came as we know, with a hundred feet on each side. On the street line, which was first drawn in the area, horse-drawn trams circulated, vehicles were replaced by the “cockroach” steam machine of which survived until 1900, when he entered the electric tram service.

CAPRICIOUS

The new system of numbers and letters did not replace entirely the oldest and most picturesque way that was used in Old Havana and its first expansion, and in which the streets were named on a whim, either by a neighbor, a famous person or event had also attracted interest from a church or a trade or a tree.

Thus, Aguacate Street is named for a fruit tree that was planted in the garden of the old convent of Belen. Aguila, the painted image of that animal in a tavern that existed in that street. Lealtad, for the cigar of that name, and Alcantarilla, which opened near the Arsenal. Not missing the irony when denominations. Such is the case in economics. It happened that a certain Candido Rubio, who owns a wood shop, built on that street, with tables of waste and greater savings, a number of houses to rent out.

San Rafael is not always so named. He was known as Del Monserrate before it led to the door of the same name of the Wall, and also was called by friends and Del Presidio where there was the rose after the Tacon Theater, Grand Theatre today. Neptune is named after the source of that deity located where the street corner with Prado, also called De San Antonio and Placeres. Suarez, who was named in honor of a senior surgeon at the Military Hospital, was Palomar Street, one that was there, that belonged to Tio Dominguez. Cervantes was the original name was Cienfuegos street, not to serve as a reminder of the great Spanish writer, but by the Cuban journalist Tomás Agustín Cervantes, director of The Paper Journal of the Havana.

SIGNS AND NUMBERS

He was the captain-general despotic Miguel Tacon, governor of the island, who undertook the paving and signage of the streets of Havana, and the numbering of premises.

It says in the document that was the summary of its mandate: “They lacked the streets to register their names and many houses of number. I put in the corners of the first cards numbered brass and the latter by the simple expedient of putting in a sidewalk even numbers and odd numbers in another. ”

This occurred between 1834 and 1838. He would not labeled or listed in Havana until 1937.

Says the historian Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring that after the end of Spanish rule in Cuba, Havana City Council began to change the street names so whimsical and without consultation, without obeying the order, plan or any system, but in response to personal interests , vanities, sycophancy and political reasons. Sometimes, recognizes the historian, the City acted out of good will. But every change always provoked the protest of the neighborhood.

Roig was the same in 1935, who proposed that they be reinstated to the streets of Havana their old names, traditional and popular, if not patriotic sentiment Cuban wounded. The names of heroes and national celebrities of culture and science with which they renamed the streets, should be reserved, according to Roig, for new streets or not yet named. It also proposed not to give any street, road or avenue, the name of any person living or not having at least ten years dead, and not remain at the discretion of the owners of the new development the name of the streets. Largely Roig arguments were accepted in the municipal authorities.

In short, no one called Avenue of the Republic to the Calzada de San Lazaro, and Jose Miguel Gomez Correa Street, in Santos Suarez. The Avenue of Mexico remains Cristina, and Neptune has never been Zenea as Palatino Cosme Blanco Herrera was not and San Rafael, General Carrillo. O’Reilly O’Reilly was not always President Zayas, as read on their cards, and do not think anybody remember since Trocadero was once America Arias. Gerardo Machado was baptized with the name Calle 23, Vedado, and Line, under Batista, began to be called Two-Way General Batista, and we know what happened.

THE MALECON

Something similar happens with the Malecon. Originally received in the early twentieth century, the name of Gulf Avenue in early stretch, one that extends between the Castillo de la Punta and the monument to Antonio Maceo.

After this stage it was called, successively, Avenue of the Republic, General Antonio Maceo Avenue, Avenida Antonio Maceo. These were the times that way, the most cosmopolitan city, came right up to the statue of the hero. From 1936 it was extended to the mouth of Almendares and new sections were named Washington Avenue, Avenue and Avenue Pi Aguilera.

But no one can identify them to call them that, if they still have those names, and all, habaneros and not allude to such action by the generic name popular Malecon. It has always been and it will.

Sources:CiroBianchiRoss/InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

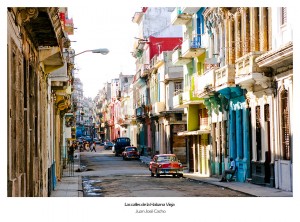

Las Calles de la Habana/ The Cuban History/ Arnoldo Varona, Editor

LAS CALLES DE LA HABANA

La Calzada de Monte se llama Máximo Gómez, y la de Reina lleva el nombre de Simón Bolívar. Como Finlay se rebautizó la vieja calle de Zanja, y Belascoaín se denomina Padre Varela. Pero ¿cuántos son los habaneros, viejos o jóvenes, que aluden a esas vías por su nomenclatura oficial? Pocos en verdad, aunque los documentos y las tabletas que las identifican insistan en recordarnos que Teniente Rey, Zulueta, Concha y Estrella se llaman Brasil, Agramonte, Ramón Pintó y Enrique Barnet, respectivamente.

¿Se ha puesto usted a pensar en el nombre que lleva su calle y por qué? Algunas se identifican con letras, otras con números. Esa manera tan racional de distinguir las calles comenzó a emplearse aquí a partir de 1858 cuando la estancia El Carmelo se convirtió en barrio residencial. Comprendía 105 manzanas que se ubican entre el río Almendres y la actual calle Paseo y desde la calle 21 hasta la línea de la costa.

Esos terrenos adquirieron mayor importancia un año más tarde, cuando el conde de Pozos Dulces y sus hermanas obtuvieron la autorización para parcelar su finca El Vedado y quedó dividida en las 29 manzanas que se extienden desde las calles G y 9 hasta los límites de El Carmelo. Fue entonces que surgió la manzana como hoy la conocemos, con sus cien metros por cada costado. Por la calle Línea, que fue la primera en trazarse en la zona, circularon tranvías tirados por caballos, vehículos que fueron sustituidos por la “cucaracha”, maquinita de vapor que sobrevivió hasta 1900, cuando entró en servicio el tranvía eléctrico.

A CAPRICHO

El nuevo sistema de los números y las letras no sustituyó del todo el modo antiguo y más pintoresco que se empleó en La Habana Vieja y sus primeras ampliaciones, y en el que las calles recibían su nombre a capricho, bien por el de un vecino, una persona célebre o un suceso que había despertado interés o también por una iglesia, un comercio o un árbol.

Así, la calle de Aguacate tiene ese nombre por un árbol de ese fruto que se plantó en el huerto del antiguo convento de Belén. Águila, por la imagen de ese animal pintada en una taberna que existió en dicha calle. Lealtad, por la cigarrería de ese nombre, y Alcantarilla, por la que se abrió en las inmediaciones del Arsenal. No faltaba la ironía a la hora de las denominaciones. Tal es el caso de Economía. Sucedió que un tal Cándido Rubio, propietario de un taller de madera, fabricó en esa calle, con tablas de desecho y los mayores ahorros, una serie de viviendas destinadas al alquiler.

San Rafael no siempre se llamó así. Se le conoció antes como Del Monserrate porque conducía a la puerta homónima de la Muralla, y se denominó también De los Amigos y Del Presidio por el que existía donde se levantó después el teatro Tacón, hoy Gran Teatro. Neptuno debe su nombre a la fuente de esa deidad emplazada donde la calle hace esquina con Prado; se llamó también De San Antonio y De la Placentera. Suárez, que recibió ese nombre en honor de un cirujano mayor del Hospital Militar, fue la calle del Palomar, por uno que allí había, propiedad del Tío Domínguez. Cervantes fue el nombre original que tuvo la calle Cienfuegos, y no para que sirviera de recuerdo al gran escritor español, sino por el periodista cubano Tomás Agustín Cervantes, director de El Papel Periódico de la Havana.

RÓTULOS Y NÚMEROS

Fue el despótico capitán general Miguel Tacón, gobernador de la Isla, quien acometió la pavimentación y rotulación de las calles habaneras, y también la numeración de los locales.

Lo dice en el documento en el que hizo el resumen de su mandato: “Carecían las calles de la inscripción de sus nombres y muchas casas de número. Hice poner en las esquinas de las primeras tarjetas de bronce y numerar las segundas por el sencillo método de poner los números pares en una acera y los impares en otra”.

Eso ocurrió entre 1834 y 1838. No volvería a rotularse ni a enumerarse en La Habana hasta 1937.

Dice el historiador Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring que tras el cese de la dominación española en Cuba, el Ayuntamiento habanero comenzó a cambiar los nombres de las calles de manera caprichosa e inconsulta, sin obedecer orden, plan ni sistema alguno, sino en respuesta a intereses personales, vanidades, razones políticas y adulonería. A veces, reconoce el historiador, el Ayuntamiento actuó movido por la buena voluntad. Pero siempre cada cambio provocaba la protesta del vecindario.

Fue el propio Roig, en 1935, quien propuso que se les restituyera a las calles habaneras sus nombres antiguos, tradicionales y populares, siempre que no hirieran el sentimiento patriótico cubano. Los nombres de próceres o de celebridades nacionales de la cultura y la ciencia con los que se rebautizaron esas calles, debían reservarse, a juicio de Roig, para calles nuevas o todavía no nombradas. Proponía además que no se diese a ninguna calle, calzada o avenida el nombre de ninguna persona viva o que no tuviese al menos diez años de fallecida, y que no quedara al arbitrio de los dueños de las nuevas urbanizaciones la denominación de sus calles. En buena medida los argumentos de Roig tuvieron aceptación en las autoridades municipales.

En definitiva, nadie llamó Avenida de la República a la Calzada de San Lázaro, ni José Miguel Gómez a la calle Correa, en Santos Suárez. La Avenida de México sigue siendo Cristina, y Neptuno nunca ha sido Zenea, como Palatino no fue Cosme Blanco Herrera ni San Rafael, General Carrillo. O’Reilly siempre fue O’Reilly y no Presidente Zayas, como se leía en sus tarjetas, y no creo que nadie recuerde ya que Trocadero fue alguna vez América Arias. Gerardo Machado hizo bautizar con su nombre la calle 23, en el Vedado, y Línea, en tiempos de Batista, comenzó a ser llamada Doble Vía General Batista, y ya sabemos lo que pasó.

EL MALECON

Algo similar sucede con el Malecón habanero. Recibió en sus orígenes, en los albores del siglo XX, el nombre de Avenida del Golfo en su tramo primitivo, aquel que se extiende entre el Castillo de la Punta y el monumento a Maceo.

Después a ese tramo se le llamó, sucesivamente, Avenida de la República, Avenida del General Antonio Maceo, Avenida Antonio Maceo. Eran los tiempos en que esa vía, la más cosmopolita de la urbe, llegaba justo hasta la estatua del prócer. A partir de 1936 se fue extendiendo hasta la desembocadura del Almendares y los nuevos tramos recibieron los nombres de Avenida de Washington, Avenida Pi y Margall y Avenida Aguilera.

Pero no hay quien los identifique para llamarlos así, si es que aún tienen esos nombres, y todos, habaneros y no, aluden a esa vía por el genérico y popular nombre de Malecón. Así ha sido siempre y así será.

Sources:CiroBianchiRoss/InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

Las Calles de la Habana/ The Cuban History/ Arnoldo Varona, Editor

The Streets of Havana

The Streets of Havana